JMU-U.Va. expand research into antibiotic resistant bacteria

Previous work resulted in surprise finding

Science and Technology

SUMMARY: The latest grant, from 4-VA at U.Va., follows $18,156 in grants from JMU and U.Va. in 2013 for the project. It was after receiving the initial grants that the researchers, Dr. James Herrick, associate professor of biology at JMU, and Dr. Stephen Turner, head of the bioinformatics core at the U.Va. School of Medicine, started developing research methodology to investigate the bacteria.

|

A $57,000 grant is helping biologists at JMU and U.Va. expand their collaborative research into understanding bacteria that are surprisingly resistant to a group of antibiotics used to treat critically ill or injured patients.

The latest grant, from 4-VA at U.Va., follows $18,156 in grants from JMU and U.Va. in 2013 for the project. It was after receiving the initial grants that the researchers, Dr. James Herrick, associate professor of biology at JMU, and Dr. Stephen Turner, head of the bioinformatics core at the U.Va. School of Medicine, started developing research methodology to investigate the bacteria that conferred resistance to antibiotics used to treat people mainly in intensive care units and burn units.

Herrick said the antibiotics that unexpectedly failed to affect the bacteria are generally used when other antibiotics fail. "They are not first-line antibiotics," he said. "These are generally reserved for use if one has an infection resistant to first-line antibiotics."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states on its website that at least 2 million people become infected with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and at least 23,000 people die each year as a direct result of these infections.

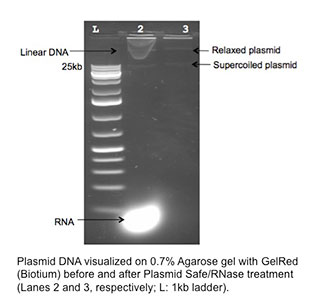

Herrick and his colleagues are now writing a paper based on findings of the earlier research that involved obtaining the DNA sequence of plasmids — small DNA molecules in bacteria that often carry antibiotic resistant genes and can transfer the resistance to other bacteria. They had found that such plasmids were common in bacteria in local streams and soils and that they conferred resistance to not only common antibiotics, but also to those that are typically reserved for human clinical use.

"What we did before was kind of a pilot," Herrick said. "We’re now going to expand. We want to get an idea of how general this phenomenon (resistance to unexpected clinical antibiotics) is."

The new grant will enable the researchers to re-analyze existing data with improved analytical methods, expand plasmid capture, use improved technology to study the genetics of the plasmids and develop novel laboratory and data analytics approaches for investigating multiple genomes sequenced together. The researchers also plan to propose a framework to annotate, curate and broadly disseminate their findings to benefit other researchers.

The new grant will enable the researchers to re-analyze existing data with improved analytical methods, expand plasmid capture, use improved technology to study the genetics of the plasmids and develop novel laboratory and data analytics approaches for investigating multiple genomes sequenced together. The researchers also plan to propose a framework to annotate, curate and broadly disseminate their findings to benefit other researchers.

"Both the genome sequencing technology and the data analysis methods are cutting-edge. It will be exciting to apply these to understand resistance to these antibiotics showing up in this environment, and how that resistance spreads," Turner said.

Herrick said evidence suggests that overuse of antibiotics, which bacteria adapt to, has led to a rapid increase in drug-resistant infections and diseases. "The fear is we are increasing the reservoir of resistance genes in the environment, and we have been for years and years and years. . . . not just in the environment, but in the natural bacteria on our skin, in our guts, in animals’ guts, their skin. These things are all exchanging genes kind of freely and not many people are looking at those, the non-pathogens."

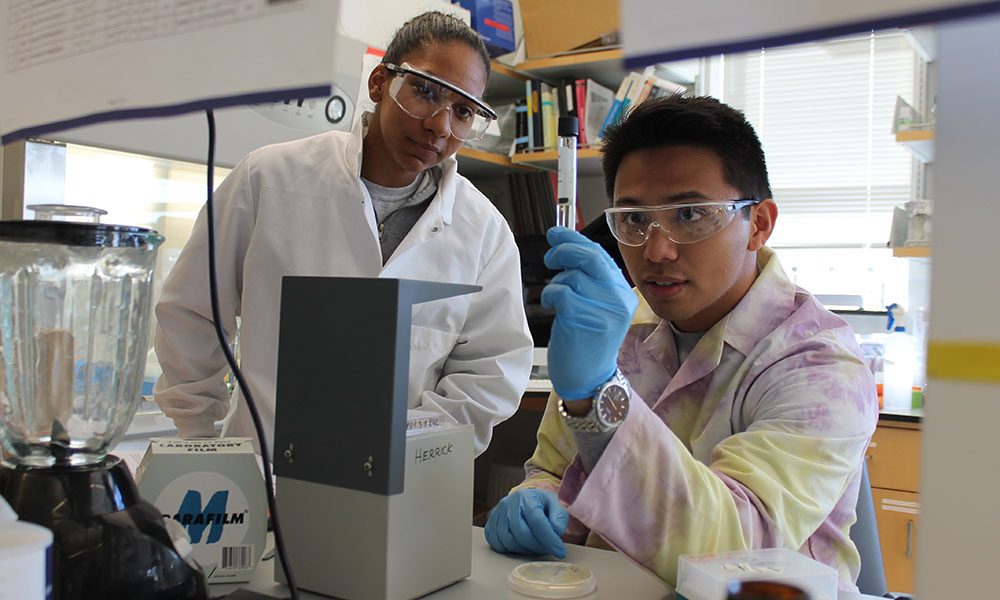

With the new money, the researchers, including JMU graduate and undergraduate students, "will be exploring this phenomenon more widely, using additional bacteria, such as the human pathogen Salmonella and the opportunistic stream pathogen Aeormonas," Herrick said.

As the project continues, bacteria samples will be collected from other streams, including a stream Herrick believes has not been affected by agriculture. "I hope that we won’t find these plasmids in the native bacteria in that stream, " he said.

In the lab, the researchers use laboratory bacteria to capture the plasmids from the bacteria collected in the streams and then test them with antibiotics; so far, tetracycline, which is mostly used in agriculture.

"But when we looked more closely at what these plasmids could do, we found that they could also confer resistance to other antibiotics," Herrick said. And thus the research will now look at some of those other antibiotics.

"But when we looked more closely at what these plasmids could do, we found that they could also confer resistance to other antibiotics," Herrick said. And thus the research will now look at some of those other antibiotics.

The U.Va. lab, run by Turner, a JMU biology alumnus, will work on the computational side of the research, analyzing DNA data collected at JMU with cutting-edge genome sequencers in the Center for Genome and Metagenome Studies. "Bioinformatics is a pretty complex computational set of skills that requires developing algorithms, that aren’t already in existence," Herrick said. "There’s no plug and play on a lot of this stuff. We can’t just find a program and use it."

Said Turner, "It's exciting to work with graduate and undergrad students. This new tech is really sparking the interest of the next generation of scientists. The training opportunity is truly unique and should result in a pretty large return on 4-VA's investment in our respective programs and institutions."

The 4-VA consortium was organized in 2010 in an effort to meet the needs of the Commonwealth identified by the Governor’s Higher Education Commission and his Jobs Commission. The original consortium consists of JMU, George Mason University, University of Virginia and Virginia Tech. Old Dominion University joined in 2015.

By Rachel Petty ('17) and Eric Gorton ('86, '09M), JMU Communications