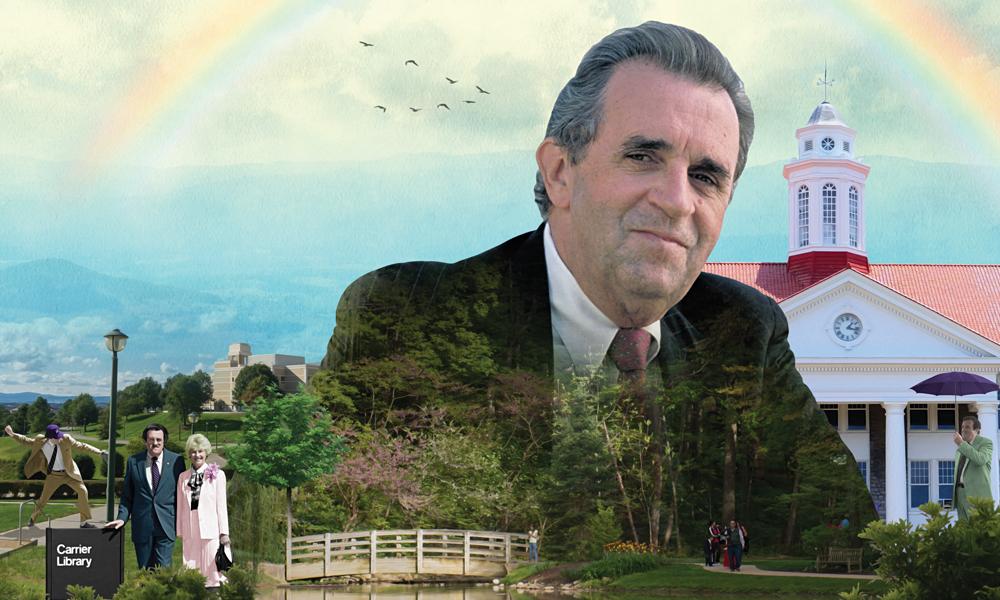

Remembering Ronald E. Carrier (1932-2017)

Education

SUMMARY: One of the country's most dynamic and effective college administrators, Carrier catapulted JMU to prominence during his 27-year presidency (1971-98) and left his mark on a grateful campus community.

from the Winter 2018 issue of Madison

Ronald E. Carrier was many things.

He was a visionary and charismatic leader who transformed a college and the local community along with it. He was the consummate political operative and lobbyist, convincing governors and legislators to support his efforts on behalf of James Madison University. He was a self-made landscape architect. He was a jock and a cheerleader. But, most of all, he was Uncle Ron.

|

Carrier's book "Building James Madison University: Innovation and the Pursuit of Excellence" has been released posthumously. Limited edition hardback copies are now available. |

When future historians write about the Carrier presidency at Madison College/James Madison University, they will most likely focus on the statistical data:

- Increasing the enrollment of around 4,000 at Madison College to nearly 14,000 at James Madison University. (Current enrollment is more than 23,000.)

- Turning a predominantly female teachers' college into a comprehensive, coeducational institution.

- Adding more than 40 new academic programs, including doctoral programs and the establishment of a studies abroad program.

- Expanding the campus by more than 100 acres and extending it across Interstate 81.

But the real change that Ron Carrier brought went far beyond buildings, books and enrollment. He changed the heart of the institution and created what is known today as the "JMU Way" —a continuing focus on the individual student. JMU became what one magazine called "a place where the student is king."

Carrier "created a culture in which all the focus of the university was on the student," President Emeritus Linwood H. Rose said. Rose was Carrier's right-hand man for many years and succeeded him as president of JMU.

|

'You have to listen to the students, they might be right.' |

"He made it clear that our reason for being was to serve the student," Rose said. "The campus culture is his true legacy."

Carrier's focus on the individual student was part of his greater plan. He wanted Madison to become a regional, comprehensive university and fill a void in Virginia's higher-education system.

By the 1970s, comprehensive universities had developed in many states. Quite often, one-time state teachers' colleges evolved into universities that offered a wide range of programs on highly residential campuses. Examples of these institutions included East Carolina University and Appalachian State University in North Carolina, the University of Southern Illinois and Carrier's alma mater, East Tennessee State University. At the time, there were 15 public colleges and universities in Virginia. They included a wide mix of institutional types, but none fit the mold of a regional, comprehensive university.

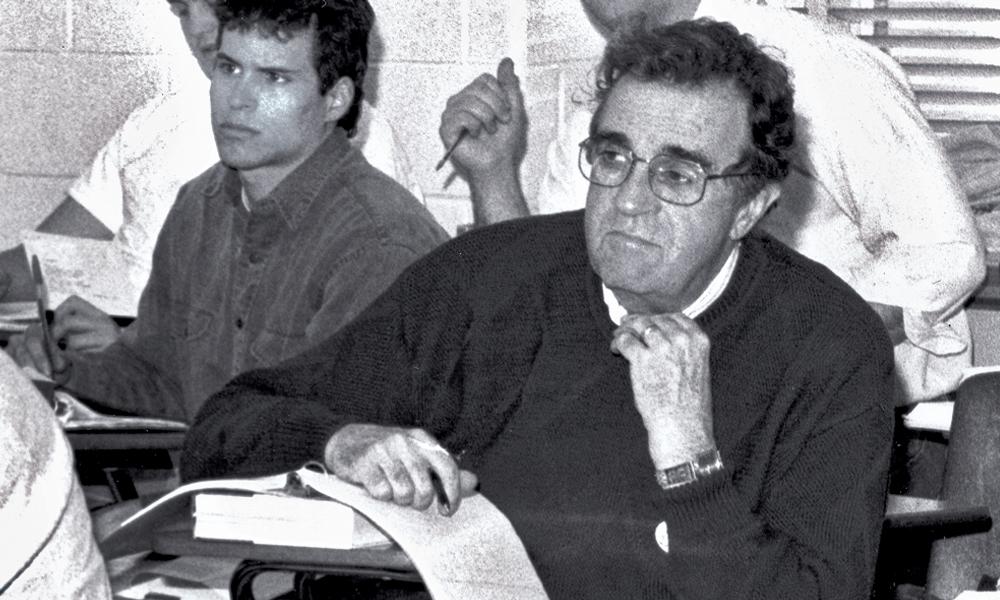

In changing JMU, Carrier operated with the mantra that "you have to listen to the students, they might be right." It didn't sound all that revolutionary, but it was practiced at precious few institutions. Colleges were usually more about the faculty and administrators than the students. Carrier quickly created Madison's new culture by seeking out its students. He walked the campus and chatted with students. He saw them in the dining halls, where he occasionally took a turn flipping burgers. He even visited a keg party or two.

An editorial in The Roanoke Times just after Carrier's death recalled those days: "He was no office-bound administrator. Throughout the '70s, '80s and '90s, the gregarious Carrier was a legendary presence on campus. He'd hail many students by name and slap high-fives as he walked across campus. When the drinking age was still 18, students would sometimes invite him to their parties. More than once, Carrier showed up in their dorm at the appointed time and knocked back a beer. Others remember shooting pool with him."

|

| When expert billiards player Jack White came to campus in the early 1980s, Carrier challenged him to a game in the campus center. |

The editorial was based on firsthand research. It was written by Dwayne Yancey ('79), editorial page editor of The Roanoke Times and former editor of The Breeze, the student-produced newspaper.

Carrier and his family originally lived on campus in Hillcrest. Often, Carrier and his wife, Edith, would invite students into their house for sandwiches and to talk about Madison and what it needed.

His visits with students in his home, his office and around campus quickly earned him the nickname of "Uncle Ron." Thousands of students attended Madison College and James Madison University during his presidency; and he was, indeed, their favorite uncle.

Carrier became Uncle Ron soon after he arrived at Madison College in 1971, but he almost declined the new job. He was only 38, but he'd already moved up the academic ladder to become vice president for academic affairs at Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis).

As the 1970s began, Carrier felt it was time to seek a presidency of his own. He was offered the presidency of a new college that was being formed in Kentucky, but he declined.

Madison College President G. Tyler Miller had announced his retirement, and Carrier was recommended to be his successor. He and Edith visited for an interview on a dismal day in October 1970, and they weren't impressed with Madison College.

Rain had turned the campus into a quagmire, and the Wilson Hall parking lot wasn't paved. "The campus wasn't in very good shape," Carrier said in an interview in 1996. "Coming from Memphis, where they were building a new building a year and adding thousands of students and adding doctoral programs and master's programs, why would you be impressed?"

He was offered the job but turned it down. But Madison's Board of Visitors persisted. The rector, Russell M. "Buck" Weaver, was particularly impressed by Carrier and Edith. Weaver and the board persevered, so on a cold morning in January 1971, Madison's new president pulled into that unpaved parking lot behind Wilson Hall.

Things would never be the same at Madison College. Uncle Ron had arrived.

|

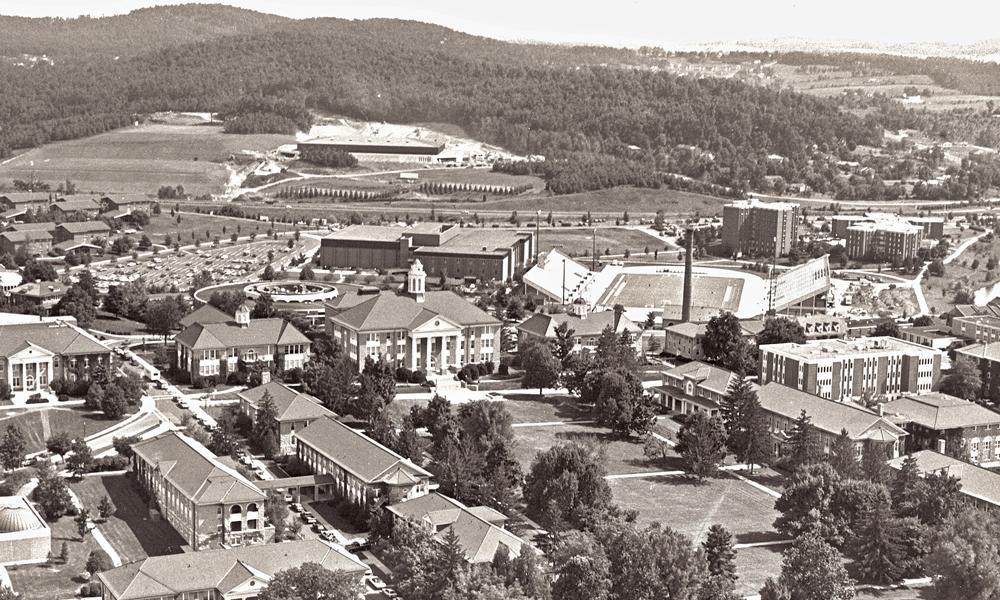

| An aerial photograph of campus, taken in the early 1980s, shows a thriving, beautiful university. Carrier recognized the value of a well-kept physical campus in welcoming new students and their families as well as providing an attractive workplace for faculty and staff. |

For the next 27 years, Madison would be in a stage of constant change—growing, expanding and improving. Shortly after he arrived as president, he said, "My administration will be characterized by an emphasis on the process of change. I'm interested in establishing procedures so that change can be made when changes should be made." It didn't take long for that muddy parking lot behind Wilson Hall to be paved. It also didn't take long for a massive building program to begin. Construction on campus became a way of life in the 1970s, and it has continued into the 21st century.

New residence halls, academic buildings, student support buildings, intercollegiate athletics and recreational facilities all went up with blinding speed. New academic programs were introduced on a regular basis.

The somewhat-draconian social rules and dress codes at the school were brought into line with other colleges. A few months after Carrier arrived on campus, some coeds were sunbathing on the Quadrangle. The dean of women came to Carrier and exclaimed: "The girls are sunbathing on the Quad! What are you going to do?" Carrier answered: "I'm going to go look at them."

On another occasion, an alumna of the old Madison College asked Carrier if "the girls are still required to wear hose for the evening meal." Carrier's response: "We're lucky to get them to wear shoes."

|

| Carrier trading places with a student as part of a fraternity fundraiser, President for a Day. |

Programs in business, the sciences and communication arts were expanded. Many of the new programs put into place were those that would appeal to male students and help balance the male-female ratio at the school. At the same time, the traditional strength of Madison's academic program—teacher education—remained strong.

The new president began a series of steps designed to make Madison a true residential college, not a "suitcase college" where students fled on the weekends to go home or visit other campuses. Athletic programs and a marching band were added; new student organizations were formed; a new campus center became the focal point for student activities.

Some of his changes put Carrier at odds with the faculty, but his support among students and the Board of Visitors remained solid.

Carrier later took the JMU campus across Interstate 81 by purchasing around 100 acres that would become the home for a broad range of academic buildings, recreational/athletic facilities, student centers and residence halls.

The biggest change made by Carrier was the change in the name of the institution from Madison College to James Madison University. At first, he was a bit reluctant to seek the name change, but staff members—primarily Vice President Ray Sonner—convinced him that Madison was now a university in every sense of the word.

The name change went to the General Assembly and, as a testament to Carrier's strong connection with legislators, the bill passed unanimously. On July 1, 1977, James Madison University came into being.

|

| Bonnie Paul and Carrier at one of the entrances to campus after JMU was granted university status in 1977. |

Carrier's popularity inside the state Capitol was legendary. He was the legislators' buddy. He joked with them, played cards with them and had a nightcap (scotch with a splash of water) or two with the real movers and shakers in Richmond. He didn't have the advantage in lobbying that the University of Virginia or Virginia Tech enjoyed, with their large numbers of alumni in the House and Senate.

In winning favor with elected officials, Carrier combined the good-old-boy persona of his native east Tennessee with the erudition of a Ph.D. of economics from the University of Illinois.

He had to depend on himself in Richmond, and he succeeded with wit and tenacity. For example, one legislator was half-heartedly chiding Carrier for seeking money for a new building when he had promised the previous session that he'd never ask for money again. "Can you explain that?" he was asked. "I lied," Carrier deadpanned.

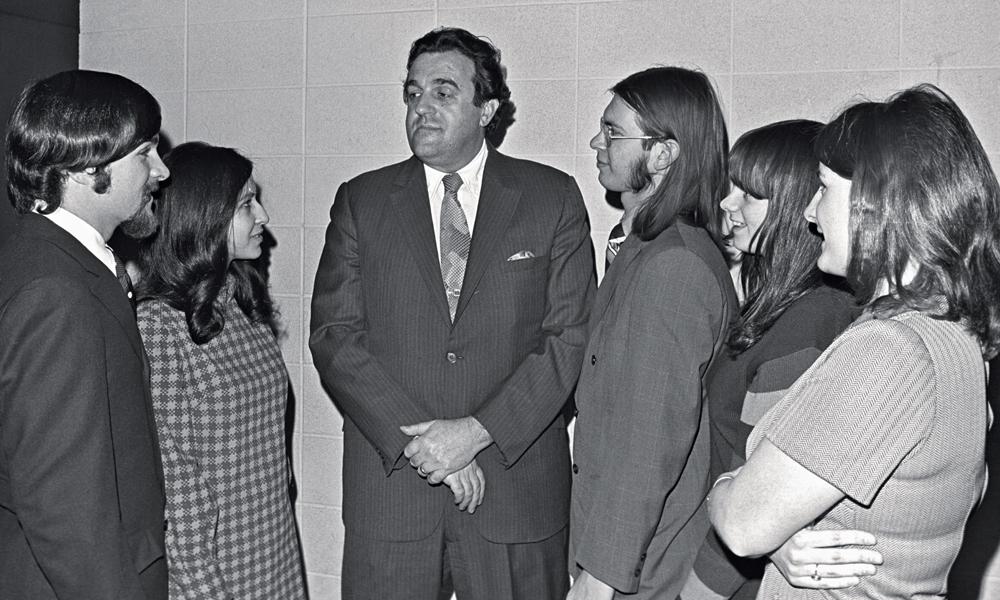

|

| Members of the Student Government Association at Madison College chat with Carrier early in his presidency. |

The new Madison president quickly became close with a series of Virginia governors and accepted special assignments from several of them. "Carrier became Mr. Fix-It for Virginia governors whenever they had some ticklish problem they needed solved," The Roanoke Times editorial said.

Linwood Holton, the governor when Carrier came to Virginia, said, "He did an outstanding job. The supporters of JMU, and indeed the entire commonwealth, are much indebted to him for what he accomplished with his leadership."

Former Gov. and current U.S. Sen. Mark Warner said Carrier "was a guide for me in the earliest days of my political life, and I considered him a trusted adviser and true friend."

|

| Carrier with Gov. Chuck Robb |

Another former governor, Gerald Baliles, told the Harrisonburg Daily News-Record that Carrier "was an educational entrepreneur. He had a creative spark of genius about him regarding academic programs, infrastructure expansion."

"When the books are written," Baliles said, "he will be seen as one of the towering figures of higher education over the past half-century."

Carrier was in constant motion. He was in his office at all hours, including weekends. He was driven to change Madison into something great. "My biggest fear is that the future will get here before I'm ready," he told JMU staff writer Martha Graham in a 1996 interview.

Throughout Carrier's 27 years of developing JMU, his wife, Edith, was by his side. The two met at East Tennessee State University where he was president of the student body and she was secretary. Carrier called her his "greatest strength." The two created a formidable one-two punch for the benefit of Madison/JMU in countless receptions, social gatherings and social events. The library on JMU's original campus is named for both of them.

One indelible mark Carrier made on James Madison University was the creation of an incredibly beautiful campus. Carrier had a love for landscaping, as did Edith. (The JMU arboretum was later named in her honor.)

Shortly after Carrier became president, it was clear that the campus was going to be turned into a place of beauty. Flowers and trees were planted. The Quadrangle and other grassy areas were carefully manicured. Newman Lake was landscaped.

Before Carrier became president, the campus would be left alone in the summer and the grass would die when there was dry weather. Carrier told one of the landscapers to make sure the Quad received a good watering. "Are you sure, Dr. Carrier?" he said. "It will just make the grass grow faster, and we'll have to cut it." Carrier's response was one that shouldn't be repeated, but the lesson took and Madison's campus became a horticultural gem.

His close relationship with the buildings and grounds crew expedited the beautification. He knew the workers by name—along with the food services workers, the housekeepers and other staff members. They were all vital to his plan to make Madison student-centered.

|

| The president with a tray of food in the campus dining hall. |

There is a famous story of an alumna saying to Carrier at a graduation ceremony that "you and the Lord have done a great job with the campus." He replied, "You should have seen it when the Lord had it by himself."

Occasionally, when funding was tight, some faculty would grouse about the money spent on flowers, saying it should have gone to faculty salaries. Carrier never wavered from his commitment to a beautiful campus—knowing that it made students, faculty, alumni and staff proud of their school, and it was a great enticement for prospective students and their parents.

Again, the underlying reason for the campus beautification was giving the students a sense of pride and ownership in their school.

Prior to Carrier's arrival, students at Madison frequently fled campus for the weekend to head home or to another campus. He wanted to end the "suitcase college" label and provide activities that would keep students on campus.

Madison had been fully coeducational for only a few years, and "I knew that we needed to change the psychology of the campus," Carrier said. Something had to be done to distinguish Madison from the other former all-women's teachers' colleges.

"We put the forces into place—the activities, the events, the new courses—that would change the attitude of people and show them that this was truly a coeducational institution," Carrier said. Football was one of the most visible of those forces.

To minimize grumbling from the faculty, Carrier waited until late summer to announce that Madison would field a Division III football team in Fall 1972. Coach Challace McMillin had to recruit most of his football team from the registration lines at the start of the new semester.

The first game was scheduled to be played on Harrisonburg High School's field, but heavy rain prompted administrators to withdraw the invitation because of fear of damage to the field. The game was played on a field next to Godwin Hall. McMillin helped in lining the field, along with Athletics Director Dean Ehlers. (McMillin and Ehlers both came from Memphis and were part of the so-called "Memphis Mafia" of Carrier's former Tennessee associates.)

|

| Carrier and Vice President Ray Sonner on the sidelines for the first Madison College football game in 1972. |

Carrier and Vice President Sonner watched the first game from the sidelines in metal folding chairs. Madison lost and failed to win a game—or score a point—in that first year's schedule against junior-varsity and military-school teams. From that humble beginning, the JMU football team would go on to win two national championships in the NCAA's Division I Football Championship Subdivision and compete in the 25,000-seat Bridgeforth Stadium.

Similar successes took place in other sports. Both men's and women's basketball programs made deep runs into the national playoffs. The baseball team became the first school from Virginia to reach the College World Series. Other sports enjoyed similar success, including national championships in field hockey and archery.

Carrier realized that a successful athletics program had a dual benefit. First, it was an important element of a student-oriented campus. It kept students from fleeing the campus on weekends, and it helped develop a camaraderie among the students.

Athletics also served as the "front porch" of a college or university—often the first thing the public sees about the school. Athletics generated publicity, which was important in spreading Madison's name and reputation as the school expanded.

|

| On the golf course with Dean Ehlers, the first appointed athletics director at Madison College and a pioneer in its growth in the 1970s and 1980s. |

Publicity, however, is a double-edged sword. Carrier greatly appreciated the positive things said in the media about Madison, but he was testy about negative press. Carrier often made his feelings known to Dick Morin, the editor and general manager of the Daily News-Record. Morin said that Carrier would sometimes call him at 5 a.m. to complain about a story—usually one on the sports page. He was "very vocal," Morin said, but "he'd buy me lunch the same day. He never stayed angry."

Madison's athletics facilities were improved campuswide to keep pace with the expanding school and its growing athletics program. The JMU Convocation Center opened, and JMU became the first Virginia school with artificial turf on its football field.

When the football stadium (originally called Madison Stadium) was being built, Carrier wanted to make sure it was finished in time for the 1974 season. Lou Frye, longtime physical plant supervisor at Madison, was knee-deep in wet concrete for the stadium.

Carrier, standing on higher ground above Frye, said, "Lou, you have to hurry and finish this job." Frye responded, "Dr. Carrier, you know Rome wasn't built in a day!" Carrier immediately said, "Lou, I wasn't in charge." Facilities for the entire student body were also modernized. Numerous playing fields were opened and the University Recreation Center opened in 1996.

|

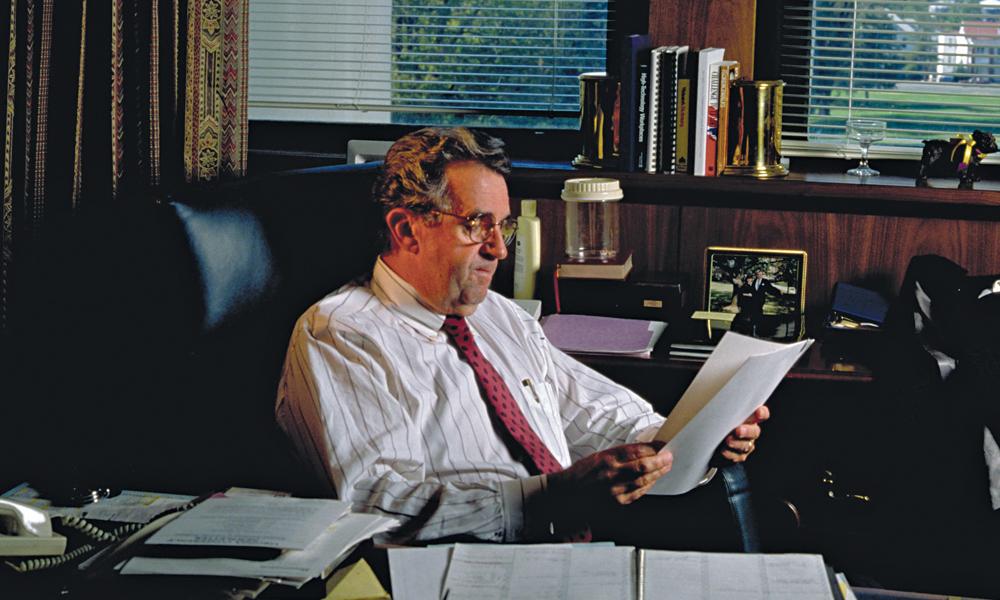

| In his office in Wilson Hall c. 1990. A Ph.D. of economics, Carrier was an avid reader who applied trends in government and industry to higher education. |

By the time he retired, Carrier had met and far exceeded his goal of creating a regional comprehensive university. He made a student-centered university that is the envy of higher education and one that continues to flourish under his successors as president.

In a tribute after his death, a Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial said that Carrier created "a selective, multidiscipline school that has given tens of thousands of students from Virginia and beyond an opportunity to earn an exceptional education. In the heart of the Valley, Ronald Carrier helped broaden the commonwealth's horizon." Carrier wasn't the school's first president but, as the Times-Dispatch observed, he was "the visionary founding father of a great university."