Student researchers help tackle Florida's python problem

Science and Technology

SUMMARY: JMU students and biology professor Rocky Parker are studying the way male pythons follow scent to help trappers in Florida better detect and capture the invasive species.

from the Winter 2018 issue of Madison

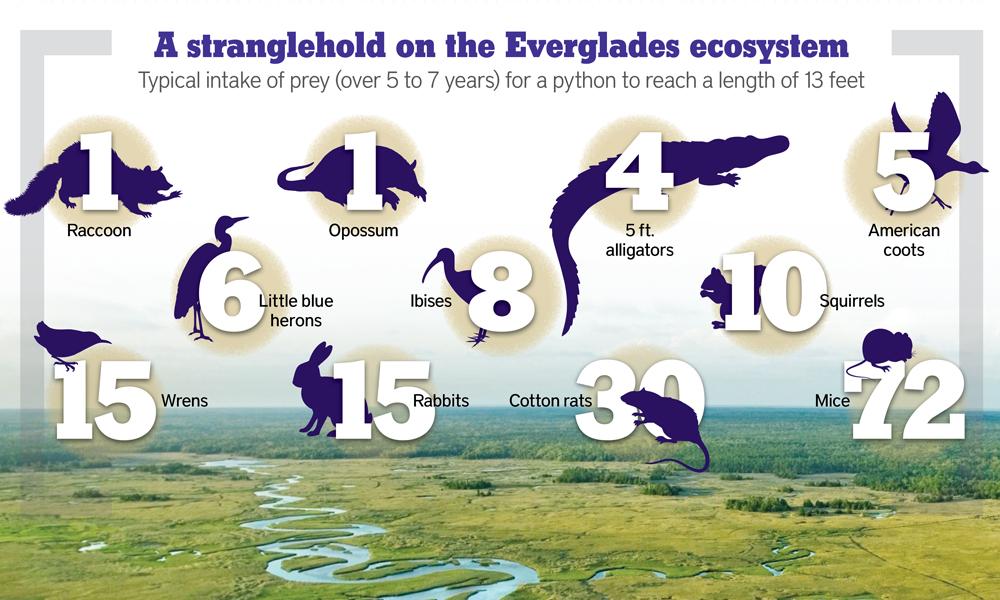

Ever since pythons got loose in Florida in the 1990s, they have become an ecological nightmare, specifically in the Everglades. Over the years, the giant snakes—which can grow to more than 20 feet long and weigh more than 200 pounds—have altered the ecology of the wetlands region by consuming native mammals and birds, costing the state not only indigenous species, but millions of dollars. Wildlife officials have tried all sorts of ways to trap and control the snakes, with varying degrees of success.

That’s where Rocky Parker, professor of biology at JMU, comes in. A chemical ecologist, Parker is trained in understanding the chemical signals that snakes use to communicate, including how they choose their mates.

|

| Parker is a professor of biology at JMU. |

With a $73,000 grant from the U.S. Geological Survey, Parker is taking a slightly new approach to his research that could significantly improve how wildlife managers find the elusive predators.

“Tracking free-ranging animals is difficult in the Everglades,” he says. “It’s a very impenetrable environment. It’s gnarly.” In addition, pythons’ skin colors and markings offer perfect camouflage. Last year, Parker, along with biology student Shannon Richard and chemistry major Ricky Flores (’17), spent countless hours studying the way male pythons follow scent. Using solvents, Flores extracted lipids from skin sheds supplied by zoos and other places that keep pythons. He then separated the chemicals based on their properties and passed those potential snake lures on to the biologists. Researchers at the National Wildlife Research Center took the compounds and put them in mazes to see if snakes would follow them. Videos were made of the snakes going through the mazes and sent back to JMU for Richard to analyze.

|

| Biology major Shannon Richard is studying the pheromone-trailing behavior of male snakes. |

“The way snakes analyze chemicals is they pick them up with their tongue and smell them,” Richard says. “A higher flick rate indicates they are more interested in the scent. So if there is a higher flick rate to the female lipid, then that’s what they are more interested in, which is what we found.”

Now Parker wants to combine what he has learned about potentially luring snakes by scent with another technique called the “Judas” approach. This approach involves tagging individual snakes with transmitters and tracking them when the animals are breeding in aggregate. Parker’s plan is to make male snakes smell like female snakes by implanting estrogen, a hormone that will trigger female pheromone production, even in males. The technique has worked in garter snakes and brown tree snakes, so it should work in pythons, Parker says. The male snakes that smell like females will attract other males and increase the number of snakes that can be trapped.

|

| Parker and his students are extracting lipids from shed python skins to isolate sexual chemical cues. The goal is to make male snakes smell like females to attract other males and increase the number of snakes that can be trapped. |

If the results are good, Parker says the approach could be used with other invasive species because hormones such as estrogen and testosterone are found in almost all vertebrates.

The project will begin with Parker’s colleagues from the U.S. Geological Survey collecting pythons. The snakes will be tracked during the mating season, which in Florida typically occurs between February and May.

“I think it’s promising,” Parker says. “Anything that increases detectability is a very useful tool, and if we can make males attractive and make other males come out of their hiding, that could crack this detectability issue, or at least help it.”

|

# # #