The loneliest black holes may also be the hungriest

JMU Headlines

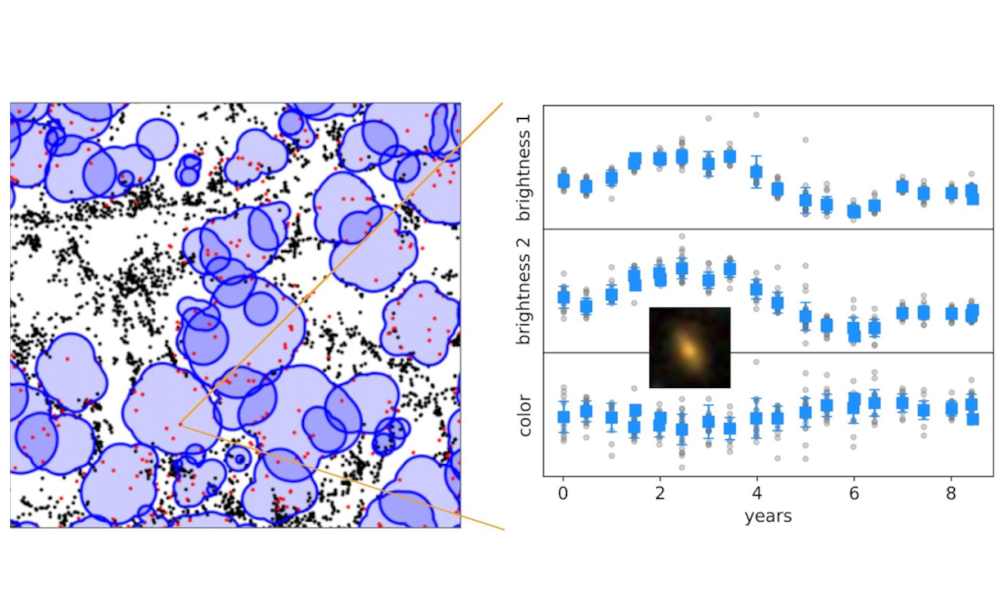

A “slice” about 30 million light years wide in the distribution of galaxies in the universe (left). Voids are shown as blue shaded regions, with galaxies within marked with red dots. The thumbnail on the right shows a void galaxy that harbors an actively accreting supermassive black hole in its center; such activity is revealed by its fluctuating mid-infrared brightness measurements. Credit: K. Douglass (University of Rochester), SDSS, A. Aradhey (Harrisonburg High School & James Madison University)

Harrisonburg, Virginia — Actively growing monster black holes — with masses millions to billions of times that of our sun — are more common within midsize and dwarf galaxies that live in the sparsest regions of the universe than in more crowded regions, a study of more than 290,000 galaxies shows.

The study, conducted by Anish Aradhey, a student at Harrisonburg High School, and Anca Constantin, a professor of astrophysics at James Madison University, used data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and more than eight years of measurements from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (AllWISE/NEOWISE) space telescope.

The findings, announced June 6 at the 242nd Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, shed light on how galaxy interactions influence galaxy evolution, suggesting that in the sparsest cosmic environments, where galaxies rarely interact, supermassive black holes are at least as adept at devouring closely surrounding gas and dust as their counterparts in more dense “urban” environments.

Voids are nearly empty three-dimensional regions of space that are hundreds of millions of light-years across and fill half of the universe. Less than 20 percent of all galaxies live in these bubble-like regions. The other 80 percent of galaxies live in crowded clusters and filaments, which one might call the cities and suburbs of the universe.

Past studies and simulations suggest that interactions between galaxies — like gravitational dances that may end in merging events, generally changing the shape of galaxies and causing them to strip matter from one another — cause the monster black holes at the centers of the galaxies to begin snacking on surrounding matter. However, this relationship is vigorously debated.

“Since these interactions are more common in crowded, urban environments, studying hungry black holes in lonely galaxies allows us to better understand the connection between galaxies’ environments and how they evolve,” said Aradhey, who plans to attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the fall.

The researchers noted that previous studies of hungry galaxies in void regions rely mostly on traditional identification methods, which examine galaxies’ mid-infrared colors and optical spectra. However, these traditional methods can miss black holes because dust can obscure the center of galaxies and because light from stars and star formation in the galaxy can outshine light from matter accreting onto the black hole. Lonely void galaxies are particularly challenging to identify because they generally have higher star formation rates.

“Quantifying variations in the mid-infrared light of galaxies has the potential to detect black holes that traditional methods miss,” said Aradhey.

Using this method, the researchers uncovered more than 20,000 actively growing supermassive black holes that remained unidentified in previous searches. Mid-infrared variability measurements revealed actively accreting black holes in more than seven percent of previously overlooked galaxies — these galaxies exhibit blue mid-infrared colors associated with vigorous star formation rather than a black hole “snacking.”

“Failure to detect actively accreting supermassive black holes may really not be due to their rarity, but to the method by which astronomers are trying to hunt for them,” said Shobita Satyapal of George Mason University, whose studies of active galactic nuclei via multi-wavelength observations — particularly mid-infrared variability — inspired this work.

Aradhey and collaborators found that for galaxies whose mid-infrared light fluctuates over time, traditional methods would miss detecting signs for accretion onto their central supermassive black holes as much as 80% of the time.

“These findings challenge our current understanding of how galaxies evolve,” Constantin added. “They show that in these reclusive galaxies, the fuel generally available for star formation is channeled towards the central black hole somewhat more efficiently than in similar galaxies in the more crowded environments,” she said.

The fact that such activity is not readily observed using more conventional methods suggests that it happens at lower levels. Constantin speculated that this might be because these rugged individuals in voids do not need to compete for fuel with their neighbors, making their life cycle less hectic.

Interestingly, galaxies in crowded environments showed a greater overall tendency to produce fluctuating mid-infrared light emissions than galaxies in the sparse voids, suggesting that actively-growing monster black holes are more common in “urban” galaxies. The trend reverses when only midsize and dwarf galaxies are compared. This offers additional support for previously proposed ideas that the life cycle of monster black hole growth in voids is delayed or slower compared to that in denser regions.

# # #

Contacts:

Eric Gorton

Media Relations Coordinator

University Communications

James Madison University

gortonej@jmu.edu

(540) 908-1760

Anish Aradhey

Student

Harrisonburg High School

anish.aradhey@gmail.com

(540) 282-7825

Anca Constantin

Professor

James Madison University Department of Physics and Astronomy

constaax@jmu.edu

(540) 568-5630