Ben Shahn Exhibition Benefits JMU Students, Madison Art Collection

College of Visual and Performing Arts

By Jen Kulju (M’04)

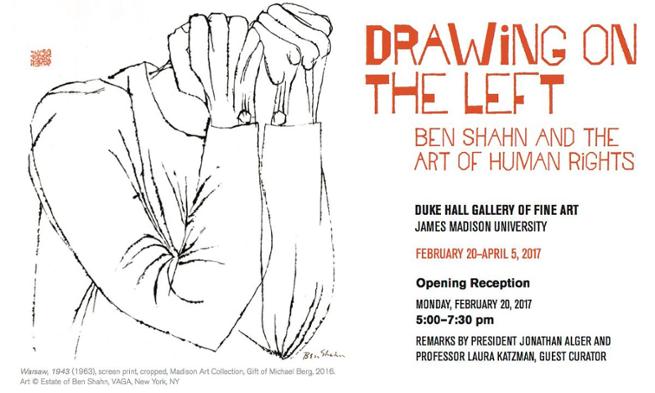

An art history major with a museum studies concentration, Meagan Stuck learned she needed one more internship credit to graduate in May 2017. That’s when art history professor Dr. Laura Katzman stepped in. Stuck had taken classes with Katzman and had gotten to know her, so when Katzman offered Stuck the opportunity to be her curatorial and research assistant for the exhibition, Drawing on the Left: Ben Shahn and the Art of Human Rights, Stuck “was happy to take it.”

Stuck is no stranger to museums. She interned at the student-run artWorks Gallery in her freshman year and the Duke Hall Gallery of Fine Art in her junior year. At artWorks, she worked with students to hang their art, and at Duke Hall Gallery, she assisted gallery director Gary Freeburg with professional installations. Stuck says these internships, as well as knowledge obtained from her museum studies coursework about art galleries and how they run, prepared her for the Ben Shahn exhibition.

An Artist with a Purpose

Born into a poor Lithuanian-Jewish family, Ben Shahn (1898-1969) was an American social realist artist and left-wing political activist who devoted his life to fighting injustice and promoting the human rights of marginalized and persecuted people. One of five children, Shahn emigrated with his family from Lithuania in 1906 and settled in the immigrant neighborhoods of Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Both Shahn and his father worked with their hands from a young age—Shahn’s father was a woodcarver and Shahn was a lithographer from age 14. He was taken out of school so that he could work to help his family survive.

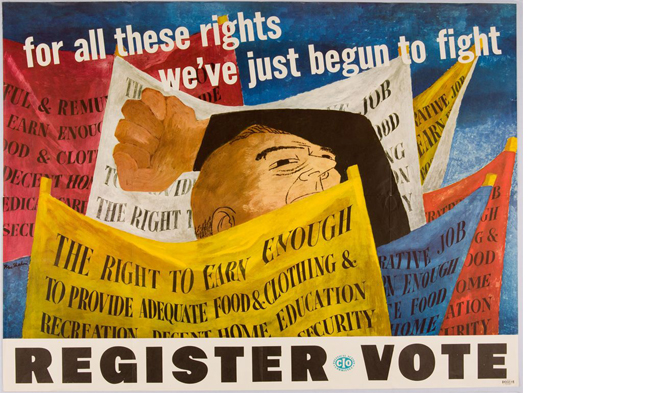

Influenced by his father’s socialistic ideals and the traditions of Orthodox Judaism, Shahn rose above his poverty-stricken childhood to become an artist of international prominence—but never forgot his roots. From the 1930s through the 1960s, he created prints, drawings, photographs and paintings that focus on issues of poverty and unemployment, racial and ethnic discrimination, the civil rights movement, and the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, among others. He worked for U.S government agencies, labor unions, political campaigns, and civil rights and peace organizations. According to Katzman, “Shahn believed in collective bargaining and in the importance of workers uniting to improve their conditions. He supported efforts to register voters, promote unions, and encourage union members to vote for presidential candidates who were pro-union.”

During the 1950s, Shahn reached the peak of his career, with his art being exhibited across the globe. At the same time, Shahn faced serious opposition to his socially charged work and political beliefs. Some influential New York critics rejected Shahn’s work in favor of art forms like Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Dada and Pop Art—and Shahn himself was blacklisted for suspected communist activity during the Cold War era. Despite the ups and downs of his life as an artist, Shahn became a champion of “humanist” content, creating art that stimulated the social conscience of a wide-ranging audience.

The Catalyst for an Exhibition

The idea for a Ben Shahn exhibition at JMU first came about after Katzman was contacted in 2012 by Fairfax-based attorney and art collector Michael Berg. Berg grew up in Roosevelt, New Jersey, the same community where Ben Shahn and his wife Bernarda lived. Berg’s parents owned the town’s only grocery store, and the Shahns were regular customers, according to Berg. “[Ben Shahn] would come into the store almost every day. He was stately and always commanded the respect of people around him.” Berg adds that the town of Roosevelt was an intellectual one, due in part to the Shahns decision to live there. The couple had first moved to Roosevelt in 1939, when [Ben] Shahn was hired to paint a government-funded mural in the local elementary school that Berg attended.

In addition to seeing Shahn’s work at school, Berg saw Shahn’s Alphabet of Creation (the Hebrew alphabet) every day in his parents’ home. In his parents’ grocery store, he saw another work, Supermarket, a print depicting shopping carts that was given to Berg’s father by Shahn when the store reopened after burning down one night. “The Shahns were people who cared about the community and cared about the well-being of others,” shares Berg. “That shows through his work.” The art given to his parents would become part of Berg’s significant collection, which today includes well-known posters and prints as well as rare and more valuable works.

Building an Exhibition

Katzman was negotiating a gift from the Ben Shahn Estate when Berg (pictured in the forefront above) reached out to her with an interest in donating work from his Shahn collection to a Virginia institution that was committed to teaching and that would use the work for various kinds of student-faculty collaborations. “The timing was serendipitous,” says Katzman. “The coincidence of these [gifts] coming together at the same time meant that the Madison Art Collection was going to have a critical mass of work around which I could build a show.” Working with Katzman, Freeburg and Madison Art Collection director Kathryn Stevens, Berg donated 10 works to the Madison Collection between 2012 and 2016. The Berg family lent a total of 31 more works for the Spring 2017 exhibition, including the Alphabet of Creation and [Michael] Berg’s Haggadah (the Jewish prayer book for Passover), which Shahn had given to him inscribed with a personal message for his bar mitzvah on February 20, 1966—51 years ago to the date of the opening of the exhibition, Drawing on the Left: Ben Shahn and the Art of Human Rights.

The Ben Shahn Estate works out of Roosevelt, New Jersey, and is largely run by Shahn’s children. The works in the Estate are those that are not in museums, galleries or private collections. Katzman, who started studying Shahn’s art for her Ph.D. dissertation at Yale University back in the 1990s, had come to know the Shahn family well, so it was only a matter of time before the Madison Art Collection would see a gift from the Estate. That gift came in 2015: 68 works including screen prints, lithographs, wood engravings, but also original drawings in pencil and ink, which are “rare and precious and often the first stages of thinking for another work of art,” reveals Katzman. “Incomplete works are useful for a teaching collection because students get to see the working process. While museums often seek signed works of art, teaching institutions consider all the pedagogical possibilities and therefore approach collecting and acquiring art with a different mindset.”

Filling in the Gaps

With gifts from Michael Berg and the Ben Shahn Estate, Katzman (pictured with Freeburg above) realized that she had the foundation for an exhibition—but needed additional works to fill in the gaps. Katzman taught at Randolph Macon Woman’s College (now Randolph College) from 1995-2007 and helped that institution to build a substantial Ben Shahn collection, so Katzman made a “natural connection” when reaching out to the Maier Museum and its director Martha Johnson. “[Laura] Katzman is one of the world’s leading Ben Shahn scholars, and we owe a debt of gratitude to her for helping to encourage collectors to place their works in our collection. So, when she contacted me, I was delighted to cooperate in any way I could,” says Johnson. The Maier Museum lent 13 works to the exhibition, including a major anti-nuclear painting called It’s No Use to Do Anymore, one of 10 in Shahn’s last series of paintings entitled The Saga of the Lucky Dragon.

In a bold move, Katzman also reached out to the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden to borrow works. The Smithsonian had not lent to JMU’s galleries before; however, Katzman had borrowed works from the Smithsonian when curating Ben Shahn exhibitions elsewhere, so she was familiar with its high standards for lending works of art. “Proper humidity, temperature, and lighting controls are important, as are security and insurance,” says Katzman. “Shahn’s works tend to be on paper, which make them particularly susceptible to humidity and light.” According to Katzman, after a year of negotiations, we “passed muster.” (Once the Hirshhorn conservator arrived at the Duke Hall Gallery to oversee the installation of its works, the lights had to be brought down to very low levels to meet the Hirshhorn’s conditions. Freeburg and his graduate student Sam Posso implemented the solution of placing on the lights handmade mesh filters to solve the lighting issue and allow for a successful installation.) The Smithsonian lent four works to the exhibition, including Shahn’s famous post-World War II era painting, Brothers, which shows two family members reuniting after one of the men miraculously escaped and survived a concentration camp in Estonia. Katzman stresses Shahn’s use of hands in this painting. “The hands are enlarged and signify comfort, reconciliation and love.”

Drawing on the Left: Ben Shahn and the Art of Human Rights

While civil rights and human rights are the main themes of the Ben Shahn exhibition, hands are a recurring motif in Shahn’s work. The signature image for the show, Warsaw, 1943, captures—with fists clenched—the anguish of the Jews who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Katzman says the image also represents a more universal message of human suffering, which is particularly poignant for an exhibition on human rights and social justice. According to Katzman, Shahn pairs the image with a Hebrew text, the 10 martyrs’ prayer, which refers to the 10 Jewish sages killed by the Romans in the second century C.E. Warsaw, 1943 is a screen print and a gift from Berg to the Madison Art Collection. The Maier Museum also loaned a version of Warsaw, 1943 (without the Hebrew text) to the exhibition. The Warsaw, 1943 pieces are two of more than 90 paintings, prints, posters, drawings, illustrated books and magazine covers in a stunning exhibition that also includes a 10x10-foot wall mural that simulates a section of one of Shahn’s well-known government-commissioned murals made for the Social Security Administration Building in Washington, D.C. between 1940 and 1942.

Demonstrating Shahn’s incisive and compassionate response to the most pressing issues in American life from the New Deal through the civil rights era, according to Katzman, this exhibition reveals the subjects that concerned Shahn and his fellow leftists: poverty, fascism, war, labor unions, the nuclear arms race, civil liberties, and racial, ethnic, and class discrimination. “The exhibition shows how the artist moved from a documentary aesthetic to a more reflective, allegorical and universal vision, where his inimitable line varies from the schematic to the lyrical.” Later in life, Katzman says Shahn “turned to philosophical and spiritual themes—drawing on Old Testament stories, the Hebrew language, and classical mythology to fuel his social commentary.” Berg’s Alphabet of Creation and Haggadah are both included in this final section of the show.

The chronology of the exhibition was purposeful. “I wanted to give audiences a clear, concise narrative in order to introduce them to Shahn. I also structured the show to be a laboratory for my museum studies students, so they could understand the making of a major exhibition from behind the scenes—and use it as a foundation for their coursework,” explains Katzman. Students were asked to brainstorm on ways to incorporate technology into the exhibition and to come up with their own public programs to coincide with the exhibition.

Katzman and research assistant Stuck worked with departments across campus to organize five public programs that were designed to complement the show. “[Stuck] has been involved in every stage of the show since September, and has been an incredible asset” says Katzman. In addition to programming, Stuck was involved in deciding what works from the Madison Art Collection would be exhibited and where they would be laid out in the show. She also helped to display the rare books in the exhibition and was able to observe the installation of paintings when the conservator from the Hirshhorn came to JMU. Katzman’s museum studies students (pictured with Katzman, Freeburg, Stuck and the Hirshhorn conservator Briana Feston-Brunet) as well as Duke Hall Gallery undergraduate interns had a chance to witness the installation as well—and to learn from the conservator about the install process, the role of a conservator, and internship possibilities at the Smithsonian.

“This experience has cemented my interest in museum work,” declares Stuck. “I’ve gotten to taste and see what curation is really like, and working with Professor Katzman has been invaluable.” Stuck admits that her knowledge was limited about Shahn before this exhibition, but says what she has learned most about his work is how politically involved he was and how his voice and ideas carry through to today. Katzman had no way of predicting the 2016 presidential results when she started thinking about the exhibition more than four years ago. However, she knew that in the spring of 2017 “issues debated in the election would still be fresh in the minds of our community.” She couldn’t have been more right. And now, thanks to Katzman’s efforts and generous donations from Michael Berg and the Ben Shahn Estate, both the JMU and Harrisonburg communities can appreciate Shahn’s culturally relevant yet timeless artwork for many years to come.

Photos by Gary Freeburg, Jen Kulju, Amelia Schmid and Greg Versen.

Artworks: Ronny Jaques, Ben Shahn (ca.1945), National Portrait Gallery; Ben Shahn, For All These Rights (1946), Madison Art Collection. @Estate of Ben Shahn, VAGA, New York, NY.