Using PowerPoint Effectively

Center for Faculty InnovationMarch 29, 2018

“Power corrupts. PowerPoint corrupts absolutely.”

—Edward Tufte

We’ve all found ourselves attending a lecture, only to be distracted by an irrelevant word bouncing onto the screen, or frantically trying to read dense text on one slide while ignoring the presenter’s explanation before she rushes on to the next slide. Such experiences may cause us to sympathize with the sentiment Tufte expressed above. It’s true that PowerPoint and other presentation software such as Keynote and Prezi can add little to, or even subvert, our intended outcomes when used improperly. However, like any tool in our toolbox, when used intentionally, they help us help students learn.

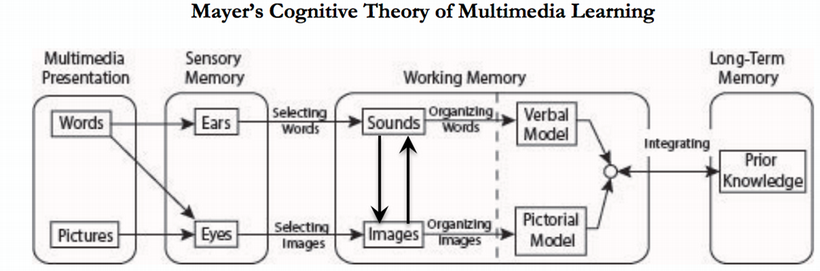

Often, the goal of a PowerPoint (or any other slide-based) presentation is to deliver information to the listeners and for it to be stored in their long-term memories. The role of our slides in this process can be understood through the “Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning” (Mayer, 2008). This topic could fill a Teaching Toolbox of its own, but the basic principles are:

- Students process information through distinct auditory and visual channels. Learning is maximized when students create both auditory and visual models that reinforce each other. Interestingly, printed text is processed through the auditory channel (because we read the text to ourselves, and it is processed the same as if it were read by someone else).

- Each channel has a limited capacity. When too much information is presented at once, it is detrimental to learning as it overloads working memory and can’t all be processed correctly.

- Not all content has the same impact on a learner. Students filter, organize, and integrate new material based on their prior knowledge.

Fig 1. Schematic representation of Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

How can we use this theory to make sure our PowerPoints advance our instructional goals rather than undermine them? There are many sources that use this framework to make specific recommendations for slide design (Daniel in Perlman et al., 2005; Cardwell et al., 2014; Berk, 2011). Common suggestions include:

- Slides should have simple and informative titles. The main point of the slide should be immediately obvious with just a glance. 30 point font or larger is recommended.

- Use images that connect directly to your point. Avoid extraneous images that can overload the visual channel or divert attention toward irrelevant information.

- Use text sparingly. Text on slides competes with our verbal explanations and place additional load on the auditory channel.

- Provide a verbal explanation to supplement the images on your slides instead of large amounts of text on slides to convey information. Students learn better from text and pictures than from either one in isolation; however, the results are best when the text is spoken, not written.

- Minimize distractions. Backgrounds and fonts should be clean and simple. Don’t use unnecessary sounds, animations, or transitions.

JMU psychology professor David Daniel, who specializes in translating psychology research into effective classroom practices, has written extensively about PowerPoint and offers a few suggestions in addition to those provided above. Daniel advises, “Don’t use PowerPoint to replace your lecture notes. PowerPoints are for your students and should be designed for their learning, not to aid your memory. You should bring separate lecture notes for your reference or use the presenter view feature.” This advice ensures we can follow the tips above without leaving out what we intended to say. He also notes that instructor style, learning objectives, and presentation mode all interact. Therefore, we should experiment using PowerPoint in different ways in different situations to learn what works best for us and our students.