Emergency Explosive Ordnance Risk Education

Lessons Learned from Ukraine

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.1 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Nick Vovk [ Danish Refugee Council ]

Following the Russian Federation military offensive launched on 24 February 2022, the context and extent of Ukraine’s explosive ordnance (EO) contamination drastically changed, leaving mine action (MA) operators with the need to provide emergency explosive ordnance risk education (EORE). Faced with scarce up-to-date guidance and good practices on the topic, the global EORE Advisory Group (AG)1 produced a refreshed document to support implementation. In September 2023, the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) also surveyed the entire MA community in Ukraine and organized a joint Lessons Learned Workshop to review the past eighteen months of emergency EORE programming. The workshop addressed various aspects of the latter, as prioritized by EORE practitioners: coordination and monitoring, informational materials, provision of EORE for persons-on-the-move and those in hard-to-reach areas, digital EORE, as well as the integration of EORE with the broader humanitarian response. This article is dedicated to summarizing the results and public discussions to inform both the global and Ukrainian EORE community of practice.

Introduction

After relocating from Donbas to Kyiv on 23 February 2022, my evacuation flight was booked for the next day. In the early hours of 24 February 2022, a Notice to Airmen was circulated as the first shelling hit Boryspil airport. Despite telltale signs, a war between Ukraine and the Russian Federation in the proportions we know today was unforeseen. In the weeks and months thereafter, millions of Ukrainians became displaced or trapped in besieged cities. The indiscriminate attacks that ensued brought about “a severe disruption of family life and community services that overwhelm[ed] the normal coping capacities of the affected people.ˮ2 From the twelfth floor of a central Kyiv hotel, I watched the emergency unfold before my eyes.

As Russian armed forces advanced through eastern, southern, and northern Ukraine, pitched battles led to the extensive use of EO by both sides.3 Reports of cluster submunitions, anti-personnel (AP) mines (including the first documented use of seismically-fused POM-3),4 and other EO surfaced daily. Exposure to shelling, armed violence, and landmine contamination quickly emerged as the top protection risk for civilians.5 In April 2022, DRC completed a rapid EORE needs assessment across fourteen conflict-affected oblasts. The results revealed that 44 percent of respondents perceived EO contamination in their areas as either dangerous or very dangerous. Almost half (49 percent) had personally encountered EO, mostly identifying long-range munitions such as artillery projectiles, guided missiles, and aircraft bombs.6 The incredible scale and scope of new EO contamination made it evident that the EORE programming used before February 2022 was no longer fit-for-purpose.

Yet, when EORE practitioners turned to academic publications, guidelines, standards, and reports on emergency EORE delivery for guidance, they were few and far between. Among the community of practice, emergency EORE programming is commonly understood to be the same as the standard EORE provision with certain context-dependent emergency exceptions. The International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) 12.10 give some general directions on the latter.7 Perhaps the most comprehensive resources on the topic are UNICEF’s IMAS Mine Risk Education Best Practice Guidebook 98 and Emergency Mine Risk Education Toolkit;9 however, both were published more than fifteen years ago. The Education in Emergencies sector has likewise been suggested as synergetic with emergency EORE, particularly when it comes to needs assessments, mass media campaigns, and coordination.10 For EORE practitioners in Ukraine, Jones’ and Crowther’s article “Provision of Emergency Risk Education to IDPs and Returnees in Ukraine” in The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction also provided contextually relevant findings from the 2014 conflict in eastern Ukraine.11

While these resources proved advantageous, there was a growing need for more updated information; in March 2022, that is what DRC proposed to the EORE AG. The EORE AG’s collective efforts culminated in the publication of the Questions & Answers on EORE for Ukraine in a matter of weeks.12 While the existing literature remains a vital, step-by-step guide to emergency EORE programming, this document offers significant updates and good practices from the past decade. These insights could be valuable for the entire MA community, but especially in the context of Ukraine.

Since February 2022, the war in Ukraine has left behind massive casualties and EO contamination, particularly affecting men in southern and eastern parts. From February 2022 to the end of 2023, the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) recorded 29,330 civilian casualties with 10,191 killed and 19,139 injured. While many more incidents await corroboration, 91 percent (or 26,717) resulted from explosive weapons with wide area effect, 1,096 (4 percent) from landmines and explosive remnants of war, and 1,517 (5 percent) from other incidents (i.e., small arms and light weapons).13 Despite ongoing survey, the national mine action authority (NMAA) already recorded 174,000 square kilometers of EO contamination (92 percent on land and 8 percent in water)14 and 2,136 hazardous areas.15 The accounts for the number of various ammunitions found in Ukraine differ—ranging from 176,16 360,17 to 40018 —but all suggest that it is vast. These include AP, anti-vehicle, and sea mines, cluster munitions, thermobaric weapons, and other unexploded and abandoned EO. The wide range and especially the quantity of explosive hazards have particularly “hampered Ukraine’s ability to maintain previous levels of agricultural production”19 as one of the world’s largest exporters of products such as sunflower oil, barley, maize, and wheat.20 The importance of the agricultural sector for the livelihoods of Ukrainians is also reflected in the casualty statistics.

Most EO-related accidents happen in the afternoons between spring and early autumn when Ukrainian people work their lands (both commercial and subsistence), spend leisure time and forage in forests or rural areas, or repair roads. Pressured by economic necessity, many accidents transpired as people tried to remove dangerous items without proper safety measures (e.g., storing or dismantling EO at home)21 in areas that were clearly marked with mine warning signs. According to casualty data, men and boys are most at-risk (87 percent), especially those working in the agricultural and transportation industries (such as farmers and tractor drivers), public sector (i.e., teachers), as well as the unemployed.22 However, the Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviors, and Practices (KABP) survey, executed by DRC and Humanity & Inclusion (HI) from August to October 2023 across six oblasts in the north, east, and south of Ukraine, showed that people with disabilities—particularly adult males, young female adults, and elderly males, respectively—display the highest propensity to engage in risk-taking behavior.23 Thus far, Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Kherson oblasts cumulatively accounted for 68 percent of recorded accidents,24 but the KABP survey identified the highest percentage of risk-taking behavior in Kyiv oblast.

However, the EORE community in Ukraine has also made significant strides in responding to the emergency. By the end of 2023, the mine action area of responsibility (MA AoR) recorded EORE activities reaching 2,962,664 people25,26 by thirteen EORE-accredited international, national, and commercial MA partners (eight more than before 2022).27 The State Emergency Services of Ukraine (SESU)—the largest provider of EORE—reported an additional 300 thousand people receiving EORE by the end of September 2023.28 The Ministry for the Reintegration of Temporary Occupied Territories also supports these efforts, primarily via small media (e.g., distribution of EORE informational materials, etc.). Accounting for 56.4 percent of all MA activities, EORE is currently implemented in twenty-three oblasts of Ukraine, a considerable scale-up since the pre-2022 times of Luhansk and Donetsk.29 The donor community has likewise substantially increased funding for MA overall: from a combined USD$31.5 million reported between 2015 and 2021 to a total of USD$262 million between 2022 and 2023 alone (a 731 percent increase).30 However, more is needed as the war continues to affect the lives, limbs, and livelihoods of Ukrainians.

In response to the evolving challenges of delivering emergency EORE activities in Ukraine, DRC organized a Lessons Learned Workshop in September 2023.31 Its content was collaboratively shaped by the EORE AG and the EORE working group in Ukraine. In preparation, DRC conducted a survey of key EORE personnel in Ukraine from the nine EORE-accredited MA operators at the time. The workshop not only featured MA operators sharing their specific practices but also fostered a platform for broader discussions. Building on these experiences and mirroring the structure of the workshop, lessons learned in five major topics are discussed next: 1) EORE coordination and monitoring in emergencies, 2) emergency EORE materials, 3) EORE for persons-on-the-move and those in hard-to-reach areas, 4) digital EORE during emergencies, and 5) integration of EORE with the broader humanitarian response.

EORE Coordination and Monitoring in Emergencies

Five years ago, Ukraine lacked the national MA structures present today. These include a mine action law, National Mine Action Standards (NMAS), an inter-ministerial NMAA, and several mine action centers (MAC) responsible for information management, quality assurance and control, monitoring, planning, and accrediting MA operators.32 As before February 2022, the MA AoR and its working groups support them in the latter. Furthermore, the MA operators engage in regular coordination with respective oblast authorities and routinely conduct community liaison during field work. During the DRC survey, the MA community evaluated the level of coordination at 3.43 on a scale of five, but only 57 percent believed that these mechanisms also provide information on the emergency context and existing humanitarian capabilities. On the topic of accreditation, while DRC can attest that it can be arduous, 71 percent of operators did not find it detrimentally affecting their emergency EORE response.

However, all nine MA operators unanimously agreed that there is a gap in the monitoring of non-accredited EORE organizations as well as options to build their capacities. By not ensuring EORE programs are aligned with NMAS and engaging in coordination mechanisms, such organizations face doing more harm than good. On the other hand, these mostly national organizations with deep-rooted local networks could benefit from a simplified and cost-exempt accreditation process coupled with support from established MA operators. Moreover, MACs shared that the NMAS on EORE require some work which affects their monitoring processes, there is a lack of training procedures and documentation, as well as insufficient testing of EORE activities.33

Emergency EORE Materials

As per good practices, all MA operators (100 percent) reviewed and amended emergency EORE materials after February 2022, very often using social and behavior change theory (86 percent). All nine MA operators attested to making their materials gender, age, disability, and diversity inclusive as well as compliant with the Do No Harm principle. The EORE community did not find that process to be expensive, but six out of nine operators claimed it took longer than expected or desired. Adjusting materials should also be a frequently iterated process, as civilians’ informational needs and preferences change over the course of an emergency just as much as the context (e.g., Kakhovka dam destruction in Kherson Oblast). The EORE community tailored emergency EORE materials to a variety of social groups: children, adolescents, adults, students, internally displaced persons (IDPs), farmers, teachers, caregivers, and social workers. As an example, the HALO Trust (HALO) included information on how to request clearance of agricultural land in their materials for farmers34 while UNICEF increased their practicality by providing a planting calendar. Many EORE materials integrated QR codes that link the people of concern with more MA information or other humanitarian services (e.g., victim assistance or legal and economic recovery aid). Large quantities of materials were needed in the Ukrainian emergency, and they were best disseminated en masse via the logistics cluster or various humanitarian convoys, especially for hard-to-reach areas.

Among the challenges related to EORE materials, operators reported diminished production capacities of printing companies due to frequent power outages and destroyed paper stocks caused by ongoing shelling. In the first months of the war, field testing was nearly impossible due to safety concerns, resulting in the use of social media surveying as an alternative to allow for rapid, albeit superficial, testing.35 Existing literature supports practices of ‘mini’ field testing in emergency settings.36 However, distributing such large quantities of printed materials may also have negative environmental consequences which further substantiates the general need for more collaboration between MA operators and environmental partners.37

EORE for Persons-on-the-Move and Those in Hard-to-Reach Areas

By the end of 2023, 5.9 million Ukrainians continue to seek refuge in European countries38 and 3.5 million remain IDPs.39 Displacement flows over a large territory and constant pendular movements between European Union states have been recognized as challenging for 57 percent of the EORE community. One respondent noted the slow population return to areas where the Government of Ukraine regained control, stating, it is “difficult to find and gather people for EORE sessions, especially in Mykolaiv.” Several operators (43 percent) engaged in EORE at refugee and IDP transit points (e.g., collections centers and border crossing points), both inside and outside of Ukraine (29 percent). DRC, for one, launched EORE programs in Poland and Moldova40 and disseminated small media to Ukrainian refugees in Greece, Italy, and Denmark. Five out of nine MA operators reported evaluating their EORE methodologies and materials for conflict sensitivity and noted that all have been well-received by people on-the-move.

The EORE community in Ukraine has found it difficult to operate in areas where the Government of Ukraine regained control (71 percent), not least due to the ban on all MA activities within 20 kilometers of the frontline.41 Therefore, reaching those most at-risk has been assessed as insufficient (57 percent), but the speed of the response as satisfactory (71 percent). SESU, HI, and UNICEF described their experience with mobile EORE teams as a solution to access issues. Targeting those most in need has a higher impact, although it will come at a cost of time, funding, reach, and staff safety. As per IMAS 12.10, “EORE during conflict must bear the security of the EORE teams in mind.”42 Operating in hostile environments has indeed pushed the EORE community in Ukraine to bolster its safety mechanisms, with additional security and medical trainings, ex-ante community desk assessment, deploying after survey, personal protective equipment, trauma first-aid kits, etc. Access to regular psychosocial support is also highly encouraged.43

Digital EORE During Emergencies

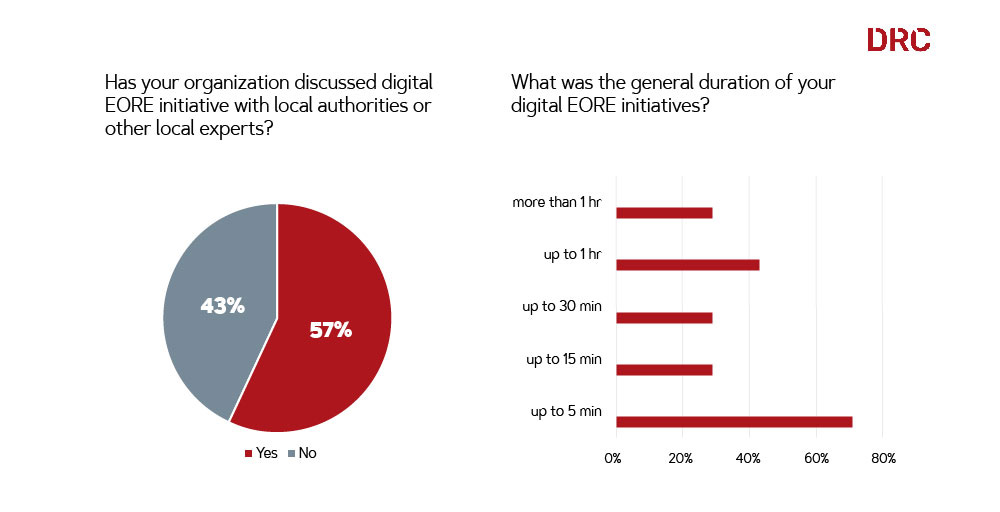

In the first month of the military offensive alone, digital EORE already reached 3.6 million Ukrainians,44 proving itself a formidable tool for emergencies. Note that the Ukrainian context is specific—with reliable internet connectivity, marketing quality, ubiquity of Web 2.0 technologies, and high digital literacy favoring these types of EORE modalities. In Ukraine, Youtube, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have been the most popular digital channels. For safety messaging, however, the Ukrainian public has heavily relied on Telegram and Viber. The most oft-used device for receiving information was a smartphone. The EORE community in Ukraine deployed several digital EORE initiatives: radio, EORE-dedicated webpages, social media and television messages, mobile applications, chatbots, online courses, augmented reality, and more. Digital EORE initiatives in Ukraine varied in length, ranging from up to five minutes to one hour long (see Figure 1). A large majority of practitioners have tailored messages and content to different medias, as attested to in the DRC survey: “creating radio ads and presenting on the local news has required us to give EORE messaging without any visual aids (…) and on television we focused our messaging on people going on holiday, as it was June at the time of year.”

There are negative aspects of using digital EORE in Ukraine as well—such as vulnerability to external hacking, hate speech, or spreading (often propagandist) misinformation. All those engaged in digital EORE should hence ensure that data privacy and other digital safety mechanisms are adequately in place since failure to do so can put both people of concern and organizations at substantial risk. Furthermore, the joint DRC and HI KABP survey showed that, in fact, “a significant proportion of survey participants express a preference for in-person communication from an expert.”45 This signals the increasing need for more critical engagement with digital EORE in the face of its growing application. To date, standards and research publications on digital EORE—especially in emergencies—remain nascent46 (e.g., references to digital EORE continue to be missing even from IMAS 12.10). That is why the EORE community in Ukraine also encountered other well-known challenges: measuring impact and behavior change,47 double counting and inflated reporting, coordination, etc.

Integration of EORE with the Broader Humanitarian Response

In Ukraine, MA operators sought integrations of EORE with both governmental and nongovernmental responses, as well as between and within humanitarian and development programs. On a scale of one to five, MA operators rated the support to government stakeholders (e.g., regional and local authorities) at 3.86. Since “[t]he primary responsibility for mine action lies with the Government of an affected state,”48 more efforts should be invested in supporting Ukrainian authorities so that they may assume the full responsibility for EORE.49 However, no emergency EORE guidance to date describes these capacity-building efforts in-depth. Currently, the community depends on adapting strategies used in post-conflict settings.50 On the other hand, integrating EORE with other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) has been a good practice for strengthening the safety of aid workers, generally, and increasing the reach of EORE, specifically. In Ukraine, MA operators rated the support to other humanitarian organizations at 4.0 on a scale of five. It is noteworthy that the demand for EORE for humanitarian workers has been overwhelming and continuous in Ukraine—the MA AoR helped produce and widely disseminate options for NGO-specific EORE sessions.51

Finally, seven out of nine MA operators had integrated EORE with multi-sectoral emergency and developmental responses and sought useful information from them. One good practice amidst an ongoing war was to integrate EORE with conflict preparedness and prevention (CPP) messaging, as was done by DRC, Norwegian People’s Aid, HI, and HALO.52 At DRC, EORE informational leaflets were also distributed in all non-food packages, as well as by the protection and legal assistance teams. EORE sessions were additionally provided to construction workers of DRC shelter and settlements programs and people of concern who received economic recovery aid, especially when part of the agricultural economy.

Conclusion

In summary, the following lessons learned arise from emergency EORE in Ukraine over a period of eighteen months (February 2022 to September 2023), as collected by the MA operators at the DRC Lessons Learned Workshop on emergency EORE:

- Globally, emergency EORE remains under-explored, with often outdated guidance. It is commonly understood that in such situations standard EORE programming with context-specific adjustments should be practiced. However, more critical and current publications, as well as training on emergency EORE should be promoted by the entire community of practice;

- Emergency coordination mechanisms not only play a critical role in coordination; they should also regularly compile and share information on the emergency context and existing EORE and other humanitarian capabilities;

- As the need for EORE increases, non-accredited EORE organizations will emerge. In Ukraine, MACs need to ensure a simplified and cost-exempt accreditation process for them as well as conduct regular monitoring. MA operators should support the capacity building of local EORE organizations;

- The process of revising EORE materials in times of emergencies will be lengthy and needs to be frequently reiterated to ensure a people-centered, context-specific design; however, field testing will be limited due to safety issues. Online ‘mini’ field-testing modalities may be employed to bridge this gap;

- Large quantities of EORE materials will be needed in emergency situations but the private sector may not be capable of producing them. In such circumstances, producing materials in neighboring countries could be a viable option. The environmental impact of this modality at such a scale, however, merits consideration;

- International displacement and pendular demographic movements may necessitate regional EORE responses to adequately inform and educate individuals before they return to EO contaminated countries;

- Operating in newly accessible areas will be challenging, resulting in obstructed access to those most at-risk. Targeting the latter has a higher impact, but it will come at a cost of time, funding, reach, and staff safety. Strengthening safety mechanisms for EORE staff in emergencies is highly recommended;

- Digital EORE has proven to be an effective tool in emergency EORE response due to its safety, cost-effectiveness, and reach potential. It is, however, open to external hacking, hate speech, or spreading misinformation. Data privacy, inter alia, is therefore a key consideration to ensure the principle of Do No Harm. Moreover, there are unaddressed challenges when it comes to digital EORE due to generally underdeveloped frameworks;

- There will be a high and continuous demand for the provision of EORE to other humanitarian workers, from the start of emergencies onward. It is prudent to develop NGO-specific EORE sessions to best cater to this need in advance and widely disseminate these options among the engaged humanitarian sector;

- Integrating CPP messaging (as well as non-MA humanitarian aid options) with EORE will prove advantageous, especially during the ongoing armed conflicts;

- In Ukraine, more EORE capacity-building efforts ought to be invested in supporting Ukrainian authorities in assuming their primary MA duties. This, in turn, may also lead to a greater integration of EORE in both humanitarian and development activities (e.g., formalization within the educational system). Globally, the EORE community of practice necessitates more precise guidance on and good practices of EORE capacity building of national stakeholders in emergency contexts.

See endnotes below.

Disclaimer: This article and workshop were possible thanks to the financial support of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. The contents of this document are the responsibility of the author. The views expressed in this document should in no way be regarded as the official position of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands or DRC. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and DRC are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained in this document.

Nick Vovk worked for DRC in Ukraine from 2019 to 2023. During this time, he was responsible for grants management and fundraising, integrated humanitarian mine action and development projects, as well as explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) and victim assistance (VA) portfolios across Ukraine. He has also technically managed DRC’s EORE programs in Poland and Moldova. He served as DRC’s standing member in the EORE AG and was the Ukraine VA working group founder and coordinator. Prior, he was supporting research projects at the Slovenian Research Agency and was the assistant director of an academic think-tank in Slovenia. He also worked for the United Nations Development Programme in Kosovo. He holds a Master of Philosophy in development studies from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom) and two Bachelor of Arts degrees in cultural anthropology and philosophy from the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. He is qualified in explosive ordnance disposal IMAS level 3, non-technical survey, and EORE.

Nick Vovk worked for DRC in Ukraine from 2019 to 2023. During this time, he was responsible for grants management and fundraising, integrated humanitarian mine action and development projects, as well as explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) and victim assistance (VA) portfolios across Ukraine. He has also technically managed DRC’s EORE programs in Poland and Moldova. He served as DRC’s standing member in the EORE AG and was the Ukraine VA working group founder and coordinator. Prior, he was supporting research projects at the Slovenian Research Agency and was the assistant director of an academic think-tank in Slovenia. He also worked for the United Nations Development Programme in Kosovo. He holds a Master of Philosophy in development studies from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom) and two Bachelor of Arts degrees in cultural anthropology and philosophy from the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. He is qualified in explosive ordnance disposal IMAS level 3, non-technical survey, and EORE.