Working to Prevent and Reduce the Impact of Armed Violence in Coastal West Africa

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.1 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Clément Meynier [ Mines Advisory Group ]

In recent years, West Africa has experienced an alarming escalation in violence, leading to dramatic cost to human life and political instability in the region. The Sahelian states, encompassing Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, have seen a surge in deaths and injuries due to armed conflicts and violence, with a majority of violent events happening within 50 kilometers of their shared borders.1 Conflicts and unrest have caused widespread displacement, with millions fleeing their homes. As part of his New Agenda for Peace, in July 2023, the United Nations Secretary-General highlighted how the proliferation, diversion, and misuse of small arms and light weapons (SALW)2 “undermine the rule of law, hinder conflict prevention and peacebuilding, enable criminal acts, including terrorist acts, human rights abuses and gender-based violence, drive displacement and migration, and stunt development.”3 Countries in the West Africa region, particularly in the Sahel, are harsh testimonies of how weapons contribute to the destabilization of societies, and how their proliferation fuels and prolongs conflict, hindering humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding assistance.

The Problem: Spillover of Violence

Coastal West African states, namely Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, and Benin,4 are now increasingly witnessing the effects of the Sahel's crisis in their territory. Violent events in the subregion have increased by more than 200 percent between 2018 and 2022,5 with a particular increase in armed clashes, attacks, and use of improvised landmines in border areas. While the coastal West African countries are not as fragile as the Sahel, they nonetheless exhibit structural vulnerabilities, perpetuated by a north-south divide in development and economic opportunities.6 Non-state armed groups (NSAGs) are exploiting mounting grievances among disenfranchised groups in peripheral communities, especially in the north of the littoral region, capitalizing on socioeconomic marginalization, intercommunal violence, and illicit supply chains.7

Sahelian countries’ relationships with their southern neighbors is steeped in history, demography, economics, and politics. Transnational links facilitate regular movement of migrants, herders, and merchants, including illicit smugglers moving artisanal gold, narcotics, and arms. Transhumance—the migration of people and their livestock between grazing land in tandem with the seasons and their respective weather conditions—has been cited in Benin as one of the major problems to be tackled in the fight against the proliferation of weapons. As an extension of the Sahel, these border areas have practical benefits to NSAGs, serving as a rear base for rest and logistics. The region’s topography and border characteristics play a particular aggravating role due to their remoteness and lack of physical demarcation.8 Climate change, the reduction of arable and grazing land, and climate-driven migration increases movement and exacerbates tensions between farmers and herders.9 Border communities, in areas where the government has a governance deficit10 and where it offers fewer services, are particularly susceptible to the influence of NSAGs and criminal networks navigating between the Sahel and coastal countries.

Proliferation of Weapons

The aftermath of conflict in Libya has left a significant impact on the proliferation of weapons in West Africa. Putting an accurate number of weapons in circulation in the region is nearly impossible. Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) estimates that about 10 million illegal SALW are in circulation in West Africa.11 The Small Arms Survey estimates that 10,972,000 of the 40 million firearms outside of government control in Africa are spread across West Africa (2.9 firearms per 100 persons).12 Research by Small Arms Survey explored the link between the spread of insecurity and instability across the Sahel region and the increase in the demand for SALW.13 This now seems to be the case for coastal countries, where states’ security providers seek to acquire new weapons to counter insurgencies and where civilians seek to protect themselves against insecurity in areas where governments are less present.

Acquisition by states. Given how the security situation developed in the Sahel, Coastal West African governments are rightly worried about the changing situation. Significant efforts have been deployed on border security and increased military presence in border zones.14 Cooperation between states is increasing, as is the demand for military assistance, equipment, and training.15,16 Faced with increasingly frequent attacks, states are seeking to speed up acquisition of military equipment17 to be deployed in border areas.18 The increasingly lucrative armament market is not immune to geostrategic influence and expanding links with new commercial partners, such as China or Russia and private groups.19

In addition to arming their own military forces, Sahel states have also sought support and have legalized20 and provided weaponry to self-defense groups to compensate for limitations in their military operations against NSAGs in some areas.21,22 While coastal states have not mobilized such groups, patterns of collaboration between state security forces and pre-existing self-defense groups23 or traditional hunters' associations24 have emerged progressively in these regions,25 with risks that they further involve transfer of state-owned weapons.

Demand for weapons by civilians. Growing insecurity in the region has prompted states as well as residents to arm themselves,26 initially with hunting rifles and then with more sophisticated weapons.27 Smugglers and traffickers respond to demand for weapons from communities along smuggling routes and in border areas who have increasingly sought to arm themselves in response to community tensions, civil conflict, the presence of NSAGs, and banditry.28 It is estimated that weapons held by civilians account for more than 95 percent of weapons holding in coastal countries.29 However, this does not inform about the type of firearms possessed, how they are produced, and how they circulate.

Seized weapons in several Sahelian countries originated from Ivorian state stockpiles, which poured out of Côte d’Ivoire in the aftermath of its civil war from 2002–2007.30 After the post-election crisis, the trust between communities and between the population and authorities remained tenuous, leading to a substantial number of civilians preferring to retain their weapons rather than disarm.31 To some extent, this is also the case for Liberia and Sierra Leone, where conflicts have had a profound impact on the circulation of weapons among civilians. The high demand for arms and ammunition has given networks, particularly in Libya, an opportunity to continue a lucrative trade. Stocks gathered in southwestern Libya are still sold to civilians for self-defense.32 But civilians in the region also have other options to choose from outside of this illicit market.

The production of craft firearms is deeply embedded in West Africa’s culture and history with reported craft production in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, and Benin. Fabrication of craft artisanal weapons has been reported as a concern in nearly all countries of the sub-region. In some contexts, the increasing demand for weapons seems to have contributed to the development of a profitable market for craft firearm production.33 Craft firearms are no longer exclusively rudimentary items, and in several instances, their sophistication appears comparable to military-grade equipment.34 Reports suggest that gunsmiths in Ghana have the ability to manufacture semi-automatic or fully automatic weapons. The supply and demand for both craft and industrial weapons evolves according to the security context.35 Inter-communal conflict, between farmers and herders for example, may also contribute to increased demand for craft weapons.36 The ease of access to and affordability of craft weapons has made them particularly attractive possessions.37 However, the demand for craft weapons is also influenced by cultural and ceremonial practices associated with firearms. Additionally, traditional gender roles affect the demand for weapons. In numerous cultures, firearms serve as an important marker of masculinity, both as a tool for exercising protection and as a sign of men's adherence to the masculine warrior ideal. Craft weapons are no less dangerous and deadly and do contribute to fueling banditry, organized crime, and inter-communal conflicts. It was reported in both Ghana and Benin that a large majority of robberies were carried out with locally manufactured weapons.39

Diversion of SALW, Ammunition, Parts, and Components

Accumulation of weapons in the subregion means more potential sources of diversions are available. Despite African states' increasing efforts since 2020 to collect data on diversion, many states face challenges in recognizing diversification patterns from national stockpiles or international transfers.40

Conflict Armament Research (CAR) classifies causes of weapons diversion into six categories:41 battlefield capture; leakage due to ineffective physical security and stockpile management (PSSM); loss from national custody by undetermined means; state-sponsored diversion; state collapse where states lose or withdraw their control over stockpiles; and unknown causes. Unknown causes is when diversion is “confirmed at a specific point in the transfer supply chain; however, the cause cannot be identified with any certainty.”42 Evidence shows that the diversion of weapons from national armed forces—whether through capture on the battlefield, theft from armories, or purchase from corrupt elements in the military—is the primary source of non-state held firearms in the Sahel countries.43 The majority of industrially produced conventional weapons and ammunition in illicit circulation within the region were initially manufactured and exported legally.44 Diversion tends to occur further down the chain.45 Weapons circulating in the region can largely be traced back to the breakdown of physical stockpile security following state collapse (e.g., Libya) or to the capture of government arsenals by non-state actors or peacekeeping missions (Mali and Burkina Faso).46,47

Diversions from national stockpiles are a growing concern in coastal countries where military posts in remote areas represent increasing sources of divertible weapons and ammunition for NSAGs and criminal networks. In one of the countries where Mines Advisory Group (MAG) works, it was reported that due to the lack of proper infrastructures, military units had to bury their weapons underground at night to protect them from theft.48

States have particularly highlighted recurring issues in this context. One such issue is the lack of capacity to manage and safely store seized SALW in border areas, a shortfall that increases the risk of these weapons being diverted again. Another significant concern is the availability of parts and components that can be used to fabricate improvised explosive devices (IEDs). A recent study conducted by Small Arms Survey found that most IED incidents involved explosives and precursors made for commercial extractive and construction sectors.49 Chemicals used in mining explosives are often sourced from Ghana and Nigeria and diverted to illicit markets, including for IED construction. Additionally, captured, stolen, or recovered explosive ordnance (EO)—including mines trafficked from Chad, Libya, and possibly Sudan—have been identified as serving as IED components.50

Current Solutions and Challenges

SALW remain the primary tool for armed conflict in West Africa. The increasing recognition of the challenges posed by the illicit proliferation of SALW and their impact on security, development, and peace has been accompanied by the establishment of initiatives at the local, national, regional, and international levels. Effective SALW control initiative activities coupled with other initiatives relating to inclusive governance, conflict resolution, poverty reduction, education, etc. will play a critical role in reducing and preventing armed violence.

What resources can states mobilize? Effective weapons and ammunition management (WAM) by coastal West African states has and continues to reduce the number of illicit arms and ammunition in circulation, prevent weapon diversion, and mitigate the risk of unplanned explosions of munitions, thereby contributing to peace and socioeconomic and development efforts in the subregion.

The following are examples of progress made by coastal countries in SALW control efforts and areas where ongoing efforts of collaboration should continue to be prioritized:

National WAM baseline assessments have been used in the subregion to assist states in their efforts to comprehensively assess WAM institutions, policies, and operational processes and capacities.51 They consist of a national consultative process led by the host government that facilitates dialogue and decision-making among all relevant national stakeholders on WAM and related issues. In Coastal West Africa, national WAM baseline assessments were conducted in Cote d’Ivoire (2016/2022), Ghana (2019), Togo (2021), and Benin (2022). States should continue to update those baseline assessments on a regular basis to further inform prioritization and policy making.

Physical Stockpile and Security Management is crucial as states increase military equipment investments amid growing insecurity. However, there's a notable deficit in securing this equipment within the subregion, leading to risks of diversion and explosions.52 Coastal states, recognizing the expansive and technical nature of physical security and stockpile management (PSSM), frequently earmark it for assistance. Yet, challenges persist due to a scarcity of trained personnel and limited resources, hampering effective stockpile management and appropriate PSSM measure implementation. At the highest state levels, PSSM is often undervalued as a critical security measure, resulting in financially unattractive positions that elevate corruption risks. Integrating PSSM training with anti-corruption initiatives in partnership with other stakeholders and enhancing the stature and appeal of storekeeper and store managers’ roles can help to mitigate these issues. National focal points, such as National Commissions (NATCOMs), must persist in gaining traction in the prioritization of and investment in robust PSSM policies, procedures, and training. This commitment is essential for managing the accumulating weapons and ammunition and should form a key component of a broader national SALW control strategy.

For the past decade, MAG has sought to develop diverse solutions to ensure safe and secure storage for weapons and ammunition. Initially underestimated for their perceived "temporary" and "frail" nature, containerized armories have become one of the preferred ways forward. These refurbished containers are not only versatile in design, catering to a wide range of needs, but also offer significant advantages in the West African context. They are mobile, allowing for rapid deployment within three to four weeks from contract signing to key handover, and flexible, meeting the urgent demands of the region. Moreover, these containerized armories are cost-efficient, with expenses minimized to essential equipment and security features, and they boast a lower environmental footprint compared to traditional construction, often utilizing recycled, second-hand containers. This approach also addresses land ownership concerns, as the containers can be easily dismantled and relocated. MAG's implementation of this strategy has led to the delivery of sixty-five containerized armories across Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Cote d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo, Chad, Gambia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, proving especially valuable in remote or provisional settings. The adoption of containerized armories has accelerated, driven by their ability to meet MAG's needs for accessible, quick-response solutions in areas with limited access and for short-term projects, reinforcing their standing as a robust solution to the region's storage challenges.

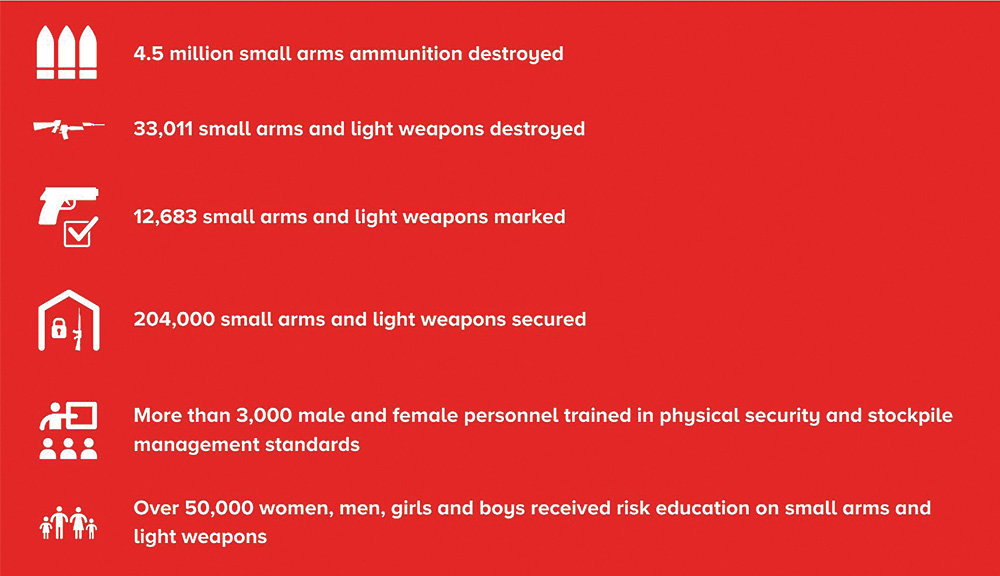

MAG has developed a vast array of trainings to respond to states’ needs. Training packages cover critical areas including weapons and ammunition store house and depot management, explosive and hazardous material handling, bulk ammunition disposal, explosive transportation, standard operating procedures (SOPs) for seized and confiscated weapons, SALW marking, and recording and disposal. In collaboration with Mauritania and Benin, MAG recently developed a training to enhance states’ capacities to lead technical evaluations of armories in line with international standards and to identify safety and security improvements. Training provided by MAG includes guidance and coaching on how to plan (design) and implement (deliver) either new infrastructure or improvements to existing infrastructure. Training needs are jointly identified with the representatives of security actors. The content is then tailored to the specific contextual needs and challenges. MAG conducts the training at central level and in locations where infrastructures are delivered to ensure sustainability of the response. Since 2014, MAG has conducted 395 training sessions across sixteen countries in West Africa, benefitting over 3,900 men and women. On average, women represent 3 percent of participants and although generally low, this rate has increased significantly in the last three years, reaching 6 percent in 2023.

Disposal and destruction. Due to resource constraints and limited technical expertise, obsolete and surplus material is frequently stored in inadequate facilities, elevating the risks of diversion and accidents. As an example, it was reported to MAG that in Benin, weapons and ammunition have been accumulated in depots since at least 1972.53 However, challenges arise not only from a lack of capacity and technical expertise but also from insufficient awareness at the highest levels about the broader benefits of proper disposal. NATCOMs and their partners can have a significant impact in garnering internal support in states to promote disposal and assist other government agencies with procedures for the handling of weapons and ammunition seized. In 2022, all coastal countries had requested technical and funding assistance to support destruction efforts.54

Each accident in the region has been a harsh reminder of the critical and lifesaving importance of disposing of obsolete and surplus ammunition.55 To prevent further risks of accidents and diversion, MAG has supported states in the safe destruction of over 998 tons of ammunition since 2014 (125 tons in 2023 only) and 33,000 SALW.

Marking. Effectively and thoroughly marking weapons supports accountability, helps maintain accurate national inventories, is a prerequisite for tracing, and is therefore a critical measure against diversion. With international assistance, West African countries in the sub-region are making remarkable progress on this in line with the ECOWAS Convention obligations.56 Imported and state-owned weapons are typically marked before distribution or dispatch. However, if this is not done, mobile marking teams are mobilized, as exemplified by the practices in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, which are considered models of good practice in the sub-region. Although marking for state-held weapons has progressed, the marking of civilian weapons, craft weapons, or seized weapons (before they are disposed of) is falling behind. Policy, SOPs, equipment, technical expertise, and resources to mark weapons are common challenges for states needing continued assistance. Policy makers, NATCOMs, and security actors need to closely cooperate to broaden marking strategies and foster in-country capacities to align practices with internationally recognized standards and commitments.

Recordkeeping. Despite the focus on marking, progress in recordkeeping has been comparatively slow. The ECOWAS Convention, aligning with international standards, mandates the creation of national and sub-regional computerized registers and databases for state-held SALW. While accounting systems for states are generally in place across the sub-region, the recording and storage of weapons and ammunition data predominantly remains paper-based. Countries like Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana have initiated steps toward digitizing and centralizing their weapons registers but are hindered by a lack of resources and technical expertise. Further cooperation to provide trusted, simple, and affordable solutions is crucial to prevent diversion.

Seeking to provide a more comprehensive response to Armed Violence Reduction, MAG has established strategic partnerships with global stakeholders in the sector. For instance, MAG has teamed up with the Centre for Armed Violence Reduction (CAVR) to assist national authorities in implementing ArmsTracker, a user-friendly, cost-free arms record-keeping system that meets global standards and is especially suited for countries with limited resources and high needs. Moreover, MAG works closely with the Small Arms Survey in several areas, including in the development and review of National Action Plans, and in undertaking research activities in various countries, which inform and refine MAG's policy and strategic focus. These new collaborations have proven to be mutually beneficial and have opened new avenues for addressing armed violence more effectively.

Weapon-collection programs play a crucial role in reducing the quantities of unwanted, illegal, and illicit weapons that could otherwise fuel armed conflicts or violence. In Cote d’Ivoire, two voluntary weapons collection initiatives were established following the end of the conflict in 2011, as part of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration efforts. Across West Africa, countries including Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Niger, Liberia, and Togo have participated in the African Union's "Amnesty month" initiative, aiming to encourage the surrender of illicitly-owned weapons without facing prosecution. While the results have been modest to date, when integrated into broader peacebuilding and development initiatives, weapon collection campaigns can effectively convey messages regarding the harmful consequences of weapons proliferation. States can work with various actors to ensure that these campaigns are conflict-sensitive, prioritizing community safety and security, while considering the specific needs of local communities.

Institutional arrangements and good governance assume a pivotal role in facilitating effective collaboration in the implementation of SALW control efforts. The ECOWAS Convention requires states to establish a NATCOM for the fight against the illicit proliferation and circulation of light weapons. In 2021, Nigeria became the most recent member state of ECOWAS to establish a NATCOM, bringing all member states in line with article 24 of the convention. NATCOMs are of paramount importance as they bring together diverse government entities to supervise and foster the implementation and coordination of arms control initiatives. Hence, it is crucial that they receive ample resources and are strategically positioned within the governmental architecture and equipped with a sufficient mandate to facilitate their role. All NATCOMs in the region have highlighted that they would need a larger mandate to operate effectively.57 This is significant because NATCOMs can bridge the gap that often exists between government leaders and military affairs. They facilitate effective collaboration between those who wield influence among high-level political actors and national security agencies to garner support for advancing SALW control priorities.

National action plans. National efforts to address the proliferation of illicit small arms are expanding in scope from PSSM to wider initiatives that consider the entire life cycle of weapons and ammunition. National Action Plans (NAPs) elaborate national priorities and outline the needs and focus of the country’s priorities in SALW control. As states strive to fulfill their obligations under the convention and integrate the Arms Trade Treaty, all subregional states, excluding Ghana, have formulated, endorsed, and assessed their NAPs. As states progressively recognize the importance of NAPs, they must ensure that their development and validation process58 is conducted in collaboration with the relevant ministries59 and civil society actors. NAPs require significant resources and technical expertise. Consultations held in the sub-region highlighted the interest of states to expand the scope of future NAPs to firearms and ammunition held and produced in the civilian sphere, as well as IEDs. In particular, issues pertaining to the licensing of firearms and to the production of artisanal weapons have been identified as key priorities.

National legal framework. Countries in the region exhibit distinct approaches to national weapons regulations and have all identified the need to implement a review of their existing national legal frameworks governing weapons and ammunition to align with international instruments and technical guidelines. States often highlight the difficulty to receive sustainable and dedicated technical assistance to develop, draft, and adopt national legislation and regulations. Regulations in countries are generally outdated and do not adequately address current challenges related to SALW control. For example, in Benin, although under revision, the current legislation only covers civilian weapons. The slowness and complexity of the licensing system and the process for obtaining a license tends to discourage civilians from taking steps that would enable them to comply with the law, perpetuating the illicit procurement of weapons.60 Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire emphasized the necessity of developing or enforcing legislation to safeguard lands in proximity to storage areas from encroachments, given the urban population expansion drawing nearer to these storage facilities. Continued collaboration among states in the region would streamline regulatory frameworks, raising public awareness and promoting compliance among security forces.

Focus on craft weapons. Despite their prevalence among various groups, the inclusion of craft weapons in laws and decrees is often ad hoc and subject to interpretation.61 The ECOWAS Convention does not distinguish between types of production. Aside from Benin, member states seeking to regulate the production of weapons and ammunition tend to adopt an indiscriminate approach that implicitly includes both industrial and artisanal production. This inevitably raises concerns as to the feasibility or relevance of legislative requirements (including licensing, marking, and recordkeeping) for many craft items produced, which are likely to deter craft producers to comply with the law. However, in regions where weapons production capacity comes from artisanal production, and where their demand and supply are on the rise, states could better account for these weapons in their regulatory frameworks, including by developing a licensing and registration system for artisanal producers and by defining procedures for marking civilian weapons. Ghana and Benin have already taken steps with sensitization workshops on the topic. Progress can be made through regional collaboration with countries in the region, such as Sierra Leone, where recent research will likely inform future regulatory approaches.

Why Collaboration Between Local Civil Society and Communities Should not be Overlooked

Civil society in West Africa is rich and the number of civil society organizations (CSOs) is growing exponentially.62 The effective policy shifts regarding SALW in West Africa can be largely attributed to the dedicated efforts of CSOs, which emerged as a key catalyst in evolving the non-binding ECOWAS moratorium into a legally enforceable convention.63 The regional network of International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA),64 known as the West Africa Network on Small Arms (WAANSA),65 collaborated effectively to spearhead the movement for a more robust arms control framework in the region.

Today, the role of civil society in SALW control efforts is well recognized in the ECOWAS Convention, as well as in international instruments. In the complex landscape of weapons proliferation in coastal West Africa, regional CSOs—such as WANEP,66 MALAO,67 or WANSAA—and local organizations, have emerged as indispensable allies for the implementation of SALW control efforts:

Grassroot connections and access to populations: CSOs have strong connections at the community level. This allows them to effectively disseminate information about laws and raise awareness about the dangers of SALW proliferation within communities. Due to their understanding of regional contexts, CSOs can discern the most relevant resources and mobilize community leaders to advocate SALW control efforts and build local capacity. As an example, in December 2023, Ghana’s National Commission on Small Arms and Light Weapons (NACSA) embarked on an awareness campaign to address the growing threat of illicit trafficking of SALW in partnership with schools, bus companies, CSOs, and the Narcotic Control Commission.

Advocacy and lobbying: CSOs are skilled in advocacy and lobbying, enabling them to influence policy and legislative changes. They act as a bridge between communities and policymakers, voicing the concerns and needs of those most affected by SALW proliferation. The WANSAA network has been particularly active in recent years, especially in Cote d’Ivoire, around the implementation of the Arms Trade Treaty in national legislation.

Research and data collection: CSOs have also largely contributed to research and data collection in the subregion. Through their community connections and understanding of regional contexts, they can provide insights into the factors driving civilians to arm themselves, as well as the socioeconomic impact of this proliferation on local communities. This information is crucial for shaping effective control strategies at the national level.

Policy-making: Based on their insights and presence on the ground, CSOs are essential to inform evidence-based policies. The inclusive processes of NAPs’ development and review are examples that show how states in the region consider CSOs as essential stakeholders for policy making and monitoring.

Representing diversity: Local organizations have the capacity to bring together a wide range of stakeholders, including marginalized and often overlooked communities. This is essential, as to be effective, SALW control initiatives should be inclusive of specific needs and experiences of all segments of the population.

Integration of SALW into local conflict resolution and peacebuilding initiatives: SALW practitioners should explore opportunities and tap into larger local or regional peacebuilding networks outside of the SALW community of practice. Incorporating SALW capacities into peacebuilding processes can more effectively address root causes and develop more context-specific solutions. Addressing the factors that lead to armed violence in the first place can help reduce the demand for weapons. This approach can also help bridge existing gaps between national agendas, such as SALW controls and the Women, Peace, and Security agenda.68

A bridge between communities and security actors: Due to the nature of their work, CSOs working in the SALW sector will inevitably develop relations and trust with security sector actors. In regions where government presence is weakened or nonexistent, CSOs within the SALW community can also serve as vital conduits of trust and communication between local communities and government entities.69 For example, in 2021, WANSAA Cote d’Ivoire conducted a study on security governance to inform policy makers about the risks of the widening gap between local communities and security sector actors, which has largely informed measures taken by the government.70

The growing expertise of civil society and grassroots connections are invaluable resources that national governments, ECOWAS, and the international community should invest in. In 2020, Ghana’s Executive Secretary of the NATCOM declared “CSOs could improve the quality of policy making by providing state agencies with a wider spectrum of information, views and suggestions on how to deal with illicit SALW and voice the concerns and needs of the minority groups who might otherwise not be heard, including women and youth.”71

MAG’s engagement and partnership approach with local CSOs in the region has greatly evolved in the past five years and continues to do so. We are working with a diverse range of local civil society actors who possess deep insights of local communities and contexts. Their presence and credibility enhance the acceptance and impact of all our initiatives, especially risk education activities, and help MAG ensure activities are sensitive to conflicts dynamics, whilst contributing to peace. They often establish networks that facilitate access to vulnerable populations, ensuring that life-saving information reaches those who need it most. In Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria, we have witnessed the growth and development of our local partners, watching them become stronger, more influential, and increasingly professional in their technical capacities to deliver tailored and safe messaging. This not only reflects the efficacy of our partnership but also holds significant implications for our broader mission. MAG is currently expending this localization strategy to Coastal West African states.

Why an Integrated and Coordinated Regional Response is Essential

Given the intertwined nature of conflicts and trafficking dynamics in the region, effective SALW control efforts inevitably require an integrated and coordinated regional response. The legally-binding ECOWAS Convention on SALW, adopted in 2006, was a progressive and innovative step to respond to a growing regional concern. The convention mandates member states to implement comprehensive SALW control measures, including establishing NATCOMs and developing action plans, while also encouraging public awareness and civil society engagement.

Under the Convention and ECOWAS’ leadership, an active SALW community of practice emerged in the region. Escalating insecurity in the past decade has spurred a multitude of initiatives aimed at addressing a multidimensional crisis. However, the risk of overlap or operating in isolation can limit effectiveness. Coordination and integrated response among the multiplicity of actors is needed in an environment where resources are ever more constrained. Following are a few non-exhaustive examples of regional initiatives and stakeholders that can foster collaboration and coordination of SALW control efforts:

ECOWAS and its SALW division play a vital role in coordinating efforts across member states to ensure a unified and effective approach to SALW control. The division supports the implementation of regional and national projects by working and liaising closely with NATCOMs and stakeholders implementing SALW activities in line with its WAM road map. But the multiplicity of challenges (trafficking, criminality, IEDs, violent extremism, climate) means that ECOWAS must ensure coordination between its own divisions and provide them with the required leadership.

The NATCOMs network operate under a common set of goals under the ECOWAS Convention. Although they operate within their national context, NATCOMs form a network that fosters collaboration, exchange of information, good practice, and streamlines approaches. Under ECOWAS leadership, NATCOMs meet annually to review the implementation of the Convention. This platform facilitates coordination between ECOWAS, NATCOMs, implementing organizations, and donors. However, political instability in recent years and the suspension of countries from ECOWAS poses a risk to the convention’s implementation, as it de facto limits regional cooperation and coordination. Although invited to the annual meeting in Dakar in December 2023, NATCOMs from Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea did not participate.

A pool of PSSM experts, in partnership with Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies in Germany, ECOWAS has been developing national and regional PSSM capacities through the training of national focal points, as well as instructors able to design and deliver training across the region and the continent.

Similarly, the Centre de Perfectionnement aux Actions post-conflictuelles de Déminage et de Dépollution (CPADD)72 in Benin has established itself as a regional center of excellence, providing training and capacity-building in PSSM activities. As an Ecole Nationale a Vocation Regionale,73 CPADD serves not just Benin but also extends its expertise and training programs to other countries in the region. This fosters collaborative efforts, uniformity in skills and standards throughout the region, enhances stability and safety, and ensures that training is relevant to the specific context. This fosters regional collaboration, consistency in skills and standards across the region, promotes regional stability and safety, and ensures trainings are contextually relevant.

Kofi Annan International Peace Training Centre (KAIPTC) builds upon Ghana’s experience supporting peacekeeping operations on the continent. KAIPTC runs training courses as well as academic programs on conflict, peace, and security, and provides a regional platform for projects and inter-agency collaboration. The center also has a research program and is strengthening its engagement with civil society organizations.

The multiple crises the region is facing have prompted the development of a multitude of platforms, mechanisms, and programs to assist states in navigating difficult issues. However, despite the overlapping nature of these challenges, there's a tendency among stakeholders to address these issues in isolation, resulting in a significant gap in coordination and cross-sectoral collaboration. While there is potential to build upon past experiences and lessons learned, there is also a concrete risk of inordinate duplication of efforts. While strategies must be nationally and regionally owned, and the primary responsibility for a coordinated and effective response lies with the affected states and ECOWAS, the international community has a key role to play.

How the International Community Can Further Support

In resource-constrained contexts where there are competing national priorities, international support is not only crucial but required by international instruments. Beyond providing much needed funding and technical assistance, this community could play the role of facilitator by bringing diverse experiences, expertise, and perspectives to the table, enabling a more comprehensive response to the multifaceted aspects of armed violence.

Supporting affected states in taking part in policy formulation and norm setting. The international community has a key role in bringing the diverse experiences and voices of affected states and communities in the sub-region to the forefront, ensuring that their perspectives inform policy development at the international level. SALW fora must ensure inclusive policy development, integrating insights from those directly impacted by SALW proliferation to ensure that policies are both effective and reflective of the nuanced realities of affected regions.

Further integration of SALW into development frameworks and assistance. Over the years, growing understanding of the negative consequences of insecurity on development was accompanied by the recognition of the role played by the proliferation of SALW in fueling insecurity, conflict, and armed violence and, thus, impeding development.74 The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides the international policy community the opportunity to approach SALW control through a developmental lens. However, SALW control is still largely considered a matter of arms control or disarmament, and existing assistance mechanisms focus too often on the instrument of violence rather than on the violence itself. For western coastal countries, addressing SALW proliferation is not simply a matter of arms control, but is a critically important component that should be embedded within conflict prevention, peacebuilding, and development of national strategies. To more effectively address the issue of armed violence in the sub-region, it is imperative that the international community seeks to better operationalize the link between conventional arms control and sustainable development within their assistance policies and funding decisions.

Cross-sector pollination. Addressing the multifaceted challenges of armed violence necessitates a multisectoral response. Too often, there is a tendency for experts to operate in isolation. Breaking down these silos is essential for developing coherent, evidence-based approaches to prevent and reduce armed violence. Integrating considerations of gender, age, diversity, human rights, and conflict dynamics into SALW control efforts is crucial. Programs must be more adaptive and better reflect the realities on the ground. By seeking to understand the drivers of armed conflict, the SALW community can better visualize contexts in which solutions may exist.

In the sub-region, MAG has joined forces with various partners under the Organized Crime: West African Response to Trafficking project led by ECOWAS. This project has been an opportunity for partners to learn from one another and to mutually reinforce each other. So has been the case with International Alert, another strategic actor MAG has developed a global partnership with to support and consolidate our progress made on gender75 and conflict sensitivity in the region.

Monitoring and reporting. Countries in the sub-region have been relatively successful with reporting with regards to their SALW international commitments. Reporting acts as a confidence-building measure, helps identify needs for international assistance, and reaffirms states’ commitment to its obligations. But the quality and accuracy of these reports differ. Given the complexity and often overlapping nature of reporting requirements, states have indicated reporting fatigue. NATCOMs in the region report difficulties monitoring and consolidating all data related to SALW control initiatives implemented on their territory. This lack of institutional memory is partly due to the lack of institutional capacity within the NATCOMs, but also because of the scope of their mandate or how they are positioned within the government architecture. It’s important that the international community maintains support to those states with their reporting practices while simplifying the reporting framework across various instruments to encourage more consistent and comprehensive compliance.

Forgotten fragile neighbors. The situation in the Sahel starkly illustrates the severe humanitarian costs of conflicts driven by the widespread proliferation of SALW and highlights the extensive efforts needed at all levels to mitigate their consequences. The recent power shifts in Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger are not only eroding democratic values but are also hindering international assistance. While it is critical to continue finding ways to support Sahelian states grappling with the impact of ongoing conflicts, the case of Coastal West Africa highlights the importance of not neglecting neighboring states. As the conflict spills southward, the international community should therefore ensure that it does not forget fragile neighbors in the region that are still working hard to prevent the spread of violence within their own borders.

Conclusion

The escalation of violent incidents in the region is undeniably putting pressure on the resilience of coastal states and local communities. Lessons-learned from the Sahel, especially concerning states' responses to rising insecurity, are invaluable. In instances where a military and security response might be unavoidable in the short term, this should not lead to indiscriminate actions or violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.76

Coastal states recognize the recent conflicts in the sub-region and the profound long-term effects that SALW have on societies. The significant progress achieved in SALW control, led by states and ECOWAS, needs to be sustained and advanced, especially with the increasing demand for weapons. Prioritizing SALW control measures is essential for policymakers at the highest political and military levels, necessitating political will, ownership, investment, and enhanced collaboration and coordination between states and ECOWAS. NATCOMs are key and strategic allies in these internal and external mobilization efforts.

However, in this context, the issue of SALW proliferation cannot be solely viewed through a security lens. SALW are both drivers and manifestations of violent conflict. The international and SALW communities' support for coastal states in their efforts to prevent and mitigate violence requires an understanding of the reasons behind weapon acquisition. The dynamics of SALW in the region are influenced by both demand and supply factors. Operating SALW activities in isolation will limit effectiveness; applying an armed violence reduction lens could deepen our comprehension of the broader context of armed violence, facilitating the incorporation of SALW control into holistic development and peacebuilding frameworks.

See endnotes below.

A very special thanks to Hélène Kuperman, Regional Head of Programmes for MAG Sahel and West Africa, for helping me in my reflections during the writing of the article. Many thanks to MAG’s Weapons and Ammunition technical experts Philippe Cima, Yacouba Kone, Arnaud Beyaert, and Brahima Coulibaly for bringing field experience to the article.

Clément Meynier is Regional Programme Support Manager at Mines Advisory Group (MAG) for Sahel and West Africa. He has fourteen years of experience working in the humanitarian and development sector in program management. Before joining MAG in 2019 as Country Director in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Clement worked for Humanity & Inclusion and the Danish Refugee Council in Morocco, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, and the Sahel.

Clément Meynier is Regional Programme Support Manager at Mines Advisory Group (MAG) for Sahel and West Africa. He has fourteen years of experience working in the humanitarian and development sector in program management. Before joining MAG in 2019 as Country Director in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Clement worked for Humanity & Inclusion and the Danish Refugee Council in Morocco, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, and the Sahel.