An Analysis of HMA Localization Efforts and a Proposed Pathway for Future Projects

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.2 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Mark Wilkinson, PhD [ DanChurchAid ], Lisa Mueller-Dormann, Camilla Roberti [ Danish Refugee Council ], and Lene Rasmussen [ DanChurchAid ]

This paper aims to address the relevance of localization in humanitarian mine action (HMA), delineating principles, challenges, and advocating for increased attention. Drawing upon evidence from localization initiatives from DanChurchAid (DCA) and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) programming, we discuss tenets we believe should guide future project design and development. Contrary to the perception that localization offers limited value in mine action, this paper argues that applying it to HMA projects is both urgent and highly beneficial. As discussions on localization in the humanitarian sphere progress, so too should the implementation of localized approaches in HMA, driven by the evolving landscape and good practices within the sector. The goal for this article is to drive further discussion and research as well as encourage the implementation of localized mine action projects more widely.

Introduction

Whilst there has been some appetite for discussion on localization in mine action, this initiative has been more broadly applied across the wider humanitarian sector. Of particular note is the Grand Bargain, an agreement that was launched during the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul.1 This agreement recognized the ever-growing need for, and evolving nature of, humanitarian needs. It also acknowledged that a key element of improving the effectiveness and efficiency of humanitarian action was in developing mechanisms to “get more means into the hands of people in need.”2 Through successive reviews, by 2021, the Grand Bargain had sixty-seven signatories (including twenty-five member states, twenty-six nongovernmental organizations (NGOs),3 and twelve UN agencies). Central to the concept of localization is increased support and space for local responders, acknowledging they are better placed to understand and address contextual challenges. But why is localization widely recognized in the humanitarian sector, yet so limited in its application in HMA?

Despite the good practices identified in the Oslo and Lausanne Action Plans, anecdotal evidence suggests the persistence of mine action direct delivery, especially clearance, by international stakeholders. This dominance is attributed to several factors: substantial investments needed to enhance technical and leadership skills, lengthy knowledge transfer processes that often exceed project timelines, and safety concerns associated with capacity development. It is probably for these reasons that localization has often translated at the operational level into nationalization—in simple terms, the employment of local staff around an international technical leadership core. But nationalization not only prevents the recognition of the potentially significant advantages in terms of efficiency and effectiveness that localization can offer to mine action, but it also falls short of the genuine commitments to the localization agenda made within the Grand Bargain. Put simply, nationalization is not localization.

Localization and the Humanitarian Sector

In 2016, when countries launched the Grand Bargain, a key aspiration was to be as local as possible and as international as necessary. Since then, localizing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been a high priority for many countries and organizations. This includes advocacy and cooperation with municipalities, local and national governments, as well as the private sector, particularly under SDG 174 and 17.9.5 In 2023, the UN Secretary General identified localization as a “key approach […] towards greater inclusion and sustainability” to ensure improved SDGs performance in its 2023 report on SDGs.6

In the same vein, with over 150 organizations as members, the Core Humanitarian Standards (CHS) have set up a system of standards within humanitarian operations aimed at strengthening accountability to affected communities—local capacity building, as well as locally-led efforts, feature strongly to foster resilience and enhance coordination. DCA and DRC are the only HMA operators that are part of the CHS alliance, further underlining the challenges encountered as well as the different approaches to localization outside of the technical realm within the mine action sector: HMA practices in ground operations that go beyond national and international standards vary significantly and localization is no exception.

Localization As a Strategy

The mine action community underscored the importance of strengthening local and national capacities at the first review conference of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention in Nairobi in 2004. Attention continued to be focused on the Maputo Action Plan (2014) and the Oslo Action Plan (2019) until full recognition of the importance of national ownership and capacity building to ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of cooperation and assistance and to reduce reliance on external expertise was given to the Lausanne Action Plan (2021). Nonetheless, the sector has not yet agreed on an overarching strategy beyond the consensus that national ownership and capacity are key for sustainable mine action efforts.

The mine action sector has only recently gone beyond its focus in clearance of contaminated square meters, and predominantly quantitative indicators, toward enhanced efforts to measure impact and outcomes. In this process, localization endeavors have taken different shapes. However, the increasingly constrained funding environment, as well as an ongoing push toward localization, too often translated into the nationalization of international positions and national/international staff ratios. This conflation risks underselling localization, neglecting the additional resources that are needed to implement trainings, and failing to provide any additional information regarding the sustainability of national actors in the long run. Further, if the aim of localization is recognizing the better contextual knowledge of local actors and fostering their independence, nationalizing international nongovernmental organizations' (INGO) staff won’t contribute to the overall localization agenda but rather slow it down, setting up potentially less viable/sustainable structures.

DRC and DCA aim at putting conflict and explosive ordnance (EO)-affected communities at the center of their activities, seeking cooperation with local actors to ensure solutions and responses meet actual needs and capabilities of local communities. By 2030, DRC’s vision is one where it systematically supports, facilitates, and strengthens local actors in their lead role in crisis response and in the advancement of durable solutions for people affected by conflict and displacement. DCA, as one of the founding organizations of Charter for Change and signatory to the Grand Bargain, has an equally strong commitment to the localization agenda enshrined within its strategy and demonstrated across the range of humanitarian activities it is delivering.

Funding and Sustainability

Obtaining dedicated funding for mine action projects which seek to pursue a localization agenda has proven extremely challenging. Whilst some donors have supported these activities—the United Nations Mine Action Standards’ (UNMAS) Partnership Project in Iraq being one important example—the construction of pathways to provide money directly to the local actor had, until very recently, been elusive. A central tenet of localization must be the financial independence of the local partner, and a key element of that is the provision of overheads directly to them. A major obstacle here is the procurement rules of many donors which often define a structural relationship between the donor and the international partner leading the localization project. This represents a bilateral relationship that provides little automatic right for the local partner to influence this power balance, nor to interface directly with project donors. It is difficult to see how a project delivery methodology that is anchored within restrictive procurement rules that controls funding transfer so tightly can be reconciled with a true localization agenda.

Funding agreements which place an international organization as the implementer and signatory to a donor agreement might also be seen as excluding the national partner from important donor interactions. Localized mine action projects must develop mechanisms to allow the INGO to facilitate international networks that give true visibility and means of engagement to the local partner. This change would be an important step in driving the necessary shift in the established norms for funding mine action to ensure localization stands a real chance of success. To give the local partner a seat at the table would be invaluable in terms of visibility, advocacy, relationship building, and ultimately, credibility and trust.

Sustainability is another element of localization that closely relates to funding. The realities of many mine action project delivery environments can place extreme pressures on international actors and local partners. Central to this issue is that the current system of funding for mine action projects often sees the donor providing funds for operational implementation based upon unpredictable available funding levels year on year. This makes it difficult for all parties to make true, long-term commitments to localization projects. Commitments to funding in the longer term are critical to build confidence and commitment to the true localization of mine action. They are also vital to provide the job security needed by local mine action staff to truly commit, with confidence, to working for local mine action actors on anything other than an ad hoc and short-term basis. Whilst localization offers significant benefits, those benefits do not come for free. Investment in localization projects by donors can pay dividends in the longer term but there must be true commitment to funding for the timescales necessary for capacity development activities to transition to true localized capacities.

The National Mine Action Authorities (NMAAs) and national authorities also have clear responsibilities in the localization agenda—this goes far beyond facilitating an environment where local actors can be seen playing a role in operational implementation. In the first instance, the NMAA must commit via its own strategic plans to recognizing the role of local actors and playing its role in helping to secure any national funding for local mine action actors. Even a commitment to managing and developing the prioritization of mine action activities and subsequent land release aligned with the activities of local mine action actors would do much to show the international audience just how seriously localization is taken and how well it can work within specific countries. Whilst for some NMAA this may require considerable attention, support, and influence, it is key in shaping the enabling environment for future localization projects.

Key Components of Localization

A conflict-sensitive, inclusive, principled, and rights-based approach should underpin localization efforts in the mine action realm. Conflict sensitivity goes beyond the Do No Harm approach and provides actors the necessary framework and tools to maximize positive impacts on conflict by strengthening local capacities for peace, building on connectors that bring communities together, and reducing the divisions and sources of tensions that can lead to conflict.

Acknowledging power imbalances, particularly in finance and material positions, and the consequent power dynamics is crucial in interactions with national and local actors working in mine action. Local counterparts are integral to society, and partnerships with INGOs may exacerbate pre-existing imbalances. Neither party, nor the interaction between them is neutral, and conflict analysis should therefore be the starting point, combined with mutual assessment of our mandates and alignment of our strategic objectives, of any localization efforts. Tensions can arise over financial control, miscommunication, legitimacy, and project design. It is likely that these power imbalances may encourage hesitation in donors considering taking localized approaches to demining. Without a clear understanding of these power imbalances, particularly in places experiencing ongoing conflict, donor funding committed to localization may therefore continue to be difficult to secure. Open communication, feedback loops, mutually agreed upon red lines, and avoidance of exacerbating conflicts in localized mine action projects may be key elements of upholding minimum standards, and encourage donors to overcome possible hesitations in supporting them.

Similarly, the importance of humanitarian principles cannot be over-emphasized. Any partnership should be assessed and pursued only if it is in the best interest of EO-affected populations and not in contradiction with the humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality, humanity, and independence. HMA, and localization efforts within it, must be rights-based, protection-oriented, and sensitive to age, gender, and other diversity factors such as ethnicity, religion, or displacement status.

Frameworks for Localization

With the focus often on quantity over quality in HMA, the documentation of good practices, training, and outcomes measurement related to localization has been sparse, and at best, taken place only at an internal organizational level. DRC and DCA teams have adopted different partnership modalities and approaches across countries and regions choosing options depending on their specific conflict/post-conflict context, strategic alignments with partners, and programmatic preferences. Despite some variations, there is a shared understanding that partnerships within HMA should revolve around capacity enhancement (technical, programmatic, support, and administrative skills); equitable relationships; visibility; funding; as well as advocacy and external engagement. What is most effective depends on the program, context, partners’ preferences, existing capacities, and experiences, and should be based on a needs assessment to understand what capacity building is needed, when, why, and for whom.

HMA quality management systems and technical qualifications are areas that deserve significant attention when it comes to partnerships. A frank discussion around risks and safety is urgently needed to transfer risks to local partners in a logical, productive, and sound manner. In our experience, offering on-site and international training opportunities is an essential step early on in localization projects that should go hand in hand with a clear split of responsibilities and accountabilities, standardized information management systems, and medical training. Programmatic and administrative/management training are often neglected and thus under-budgeted. Nonetheless, administrative and programmatic capacities are a core block of the localization architecture, and without them, the structure is not sustainable.

DCA and DRC identified challenges from an analysis of their experiences in localization projects that encompass various aspects:

- Prioritizing safety over efficiency is vital to prevent unacceptable risk transfer to local partners. Balancing efficiency, safety, and localization requires frank discussions on risk-taking and management, focusing on standards like International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) and National Mine Action Standards, as well as a duty of care toward partners.

- Localization efforts can face challenges due to the lack of a formalized supporting financial environment. Overheads are a key element to sustain organizational structures, yet the split of overhead costs poses dilemmas that require clarity to avoid skepticism from INGOs if perceived too low, or donor rejection if perceived too high.

- Partnering with government bodies or local actors affiliated with a political party, or connected to a party to the conflict, may damage an organization’s neutrality and lead to reputational risks, loss of access, and safety risks for deployed staff. Mitigating risks involves thorough conflict analysis and a sensitive approach to conflict, gender, and diversity throughout project implementation, with INGOs retaining the option to refrain from working with local actors if principled action is endangered.

National staff conduct clearance operations in Iraq. - Limited time can hinder partnership building and localization efforts, leading to rushed agreements or inadequate capacity building. Addressing these challenges requires dedicated staff with appropriate skills, mindsets, and tools, along with clear practical guidance and training opportunities, donors’ flexibility, and multi-year funding.

- Existing monitoring and evaluation indicators are not good enough. Establishing mutually-agreed qualitative and quantitative indicators, comprehensive and tailored monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning (MEAL) frameworks, at the partnership's onset are essential to effectively measure joint results and agree on joint measurement for outcomes.

Offering a New Construct: Identifying the Key Ingredients of a Viable Localized Model for HMA

In Iraq, DCA worked for three years in the delivery of a capacity development and localization project funded by UNMAS. This project forged a partnership between DCA and Health and Social Care Organization (IHSCO), a relatively new Iraqi national NGO, with the intention of supporting the localization and development of IHSCO as an Iraqi organization that could effectively engage in HMA clearance activities as an independent actor. This project saw DCA and IHSCO work toward the systematic development of organizational capacities as the same time as IHSCO operational standard operating procedures were created and implemented. IHSCO ultimately achieved operational accreditation early in year two of the project and became authorized by the NMAA (Iraqi Directorate of Mine Action) to deliver a range of operational activities. Whilst the project provided ample opportunity for learning and reflection—particularly on the relationship between donors and the international and national partner in localization projects—it also provided considerable success. In its fourth year, IHSCO is now directly funded by UNMAS to continue its mine action activities in Iraq.

In Iraq, DCA worked for three years in the delivery of a capacity development and localization project funded by UNMAS. This project forged a partnership between DCA and Health and Social Care Organization (IHSCO), a relatively new Iraqi national NGO, with the intention of supporting the localization and development of IHSCO as an Iraqi organization that could effectively engage in HMA clearance activities as an independent actor. This project saw DCA and IHSCO work toward the systematic development of organizational capacities as the same time as IHSCO operational standard operating procedures were created and implemented. IHSCO ultimately achieved operational accreditation early in year two of the project and became authorized by the NMAA (Iraqi Directorate of Mine Action) to deliver a range of operational activities. Whilst the project provided ample opportunity for learning and reflection—particularly on the relationship between donors and the international and national partner in localization projects—it also provided considerable success. In its fourth year, IHSCO is now directly funded by UNMAS to continue its mine action activities in Iraq.

Key ingredients: project planning, effective communication and relationships, strong technical leadership when required, careful risk management, and effective MEAL indicators.

![]() In Afghanistan, the DRC supported the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) implementing partners (IPs) and provided training that included Gender Equality Social Inclusion, MEAL, and livelihoods and protection assessment. In addition, DRC organized advocacy and resource mobilization training and capacity-strengthening activities for MAPA implementing partners in HMA leadership, as well as sending candidates on the explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) Level 2/3 course in Lebanon in 2024. In addition to training open to all MAPA IPs, DRC and the Mine Clearance Planning Agency (MCPA) engaged in a series of advocacy activities to ensure technical and financial support is guaranteed for mine action in Afghanistan, a country increasingly neglected due to political sensitivities. DRC and MCPA co-published the study “Localization in Humanitarian Mine Action in Afghanistan.”7 DRC and MCPA co-designed and cooperated on these efforts, ensuring active participation and visibility of both parties.

In Afghanistan, the DRC supported the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) implementing partners (IPs) and provided training that included Gender Equality Social Inclusion, MEAL, and livelihoods and protection assessment. In addition, DRC organized advocacy and resource mobilization training and capacity-strengthening activities for MAPA implementing partners in HMA leadership, as well as sending candidates on the explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) Level 2/3 course in Lebanon in 2024. In addition to training open to all MAPA IPs, DRC and the Mine Clearance Planning Agency (MCPA) engaged in a series of advocacy activities to ensure technical and financial support is guaranteed for mine action in Afghanistan, a country increasingly neglected due to political sensitivities. DRC and MCPA co-published the study “Localization in Humanitarian Mine Action in Afghanistan.”7 DRC and MCPA co-designed and cooperated on these efforts, ensuring active participation and visibility of both parties.

Key ingredients: partners mapping, vetting, due diligence, open communication, joint design of project and activities, joint planning and implementation, and focal point.

In Libya, DRC committed to cooperate with a Libyan organization to build HMA capacities from scratch. After the selection of the partner, including undergoing vetting and due diligence procedures, DRC and Libyan Peace Organization (LPO) agreed on a series of trainings to further the localization plan. These included Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) Core, basic life support (BLS), safety, cybersecurity, EOD refreshers, casualty evacuation (CASEVAC), and nontechnical survey (NTS) training held in Libya and Tunisia and organized by DRC, as well as other training delivered by external partners such as those on human resources (HR), finance management, post-clearance monitoring, and governance delivered by the Libya INGO Forum; age, gender, and diversity training delivered by Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining in Tunis; and the IMAS EOD Level 1 & 2 training delivered in Lebanon by the Regional School for Humanitarian Demining in Lebanon. At the time of writing, LPO explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) teams are deployed and tasked to deliver EORE sessions in Misurata, Tawergha, and Zletin. The LPO and DRC EOD teams are working together to conduct EOD training under the DRC EOD Task Orders in Tripoli and Tawergha. DRC will continue to work with LPO and deliver training in resource mobilization and proposal writing, as well as supporting functions such as equipment and logistics management. In only three years, DRC and LPO moved from exploratory talks to an established partnership through which LPO obtained accreditation to conduct NTS, EORE, and EOD, with teams deployed together or autonomously. Capacity strengthening, funds transfers, secondments, and continuous communication, combined with the support of LIBMAC, were instrumental.

In Libya, DRC committed to cooperate with a Libyan organization to build HMA capacities from scratch. After the selection of the partner, including undergoing vetting and due diligence procedures, DRC and Libyan Peace Organization (LPO) agreed on a series of trainings to further the localization plan. These included Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) Core, basic life support (BLS), safety, cybersecurity, EOD refreshers, casualty evacuation (CASEVAC), and nontechnical survey (NTS) training held in Libya and Tunisia and organized by DRC, as well as other training delivered by external partners such as those on human resources (HR), finance management, post-clearance monitoring, and governance delivered by the Libya INGO Forum; age, gender, and diversity training delivered by Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining in Tunis; and the IMAS EOD Level 1 & 2 training delivered in Lebanon by the Regional School for Humanitarian Demining in Lebanon. At the time of writing, LPO explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) teams are deployed and tasked to deliver EORE sessions in Misurata, Tawergha, and Zletin. The LPO and DRC EOD teams are working together to conduct EOD training under the DRC EOD Task Orders in Tripoli and Tawergha. DRC will continue to work with LPO and deliver training in resource mobilization and proposal writing, as well as supporting functions such as equipment and logistics management. In only three years, DRC and LPO moved from exploratory talks to an established partnership through which LPO obtained accreditation to conduct NTS, EORE, and EOD, with teams deployed together or autonomously. Capacity strengthening, funds transfers, secondments, and continuous communication, combined with the support of LIBMAC, were instrumental.

Key ingredients: partners mapping, vetting, due diligence, capacity enhancing and training on technical, programmatic, and administrative skills, joint deployment for EORE and EOD, and focal point.

![]() In Lebanon, DCA partnered with the Lebanese national organization Lebanese Association for Mine and Natural Disaster Action to develop their capabilities as an HMA NGO. Over a period of several years, DCA established a clear baseline of capabilities and went on to develop a comprehensive capacity development plan that focused on operational HMA activities as well as broader organizational-related functions, such as leadership and management. The capacity development element of this project resulted in the successful deployment of multiple HMA teams engaged in EORE and clearance activities—indeed, technical capacity development was probably one of the biggest achievements of this project.

In Lebanon, DCA partnered with the Lebanese national organization Lebanese Association for Mine and Natural Disaster Action to develop their capabilities as an HMA NGO. Over a period of several years, DCA established a clear baseline of capabilities and went on to develop a comprehensive capacity development plan that focused on operational HMA activities as well as broader organizational-related functions, such as leadership and management. The capacity development element of this project resulted in the successful deployment of multiple HMA teams engaged in EORE and clearance activities—indeed, technical capacity development was probably one of the biggest achievements of this project.

Key ingredients: partner mapping, baseline analysis, capacity development planning, effective communications between partners, and strong technical capacity.

Whilst each of these examples represents a stand-alone localization project within HMA, both DCA and DRC have captured considerable learning from them. Whilst some of this is contained within internal review documentation, others have already been published.8 The research conducted for this paper aims to further contribute to the body of knowledge relating to localization within HMA via the development of a proposed pathway that can be used as a guide in the development of future localization projects. This pathway draws key findings from the analysis of DCA and DRC localization activities, presenting a model that is intended to be of use in the design and development of future localized HMA projects.

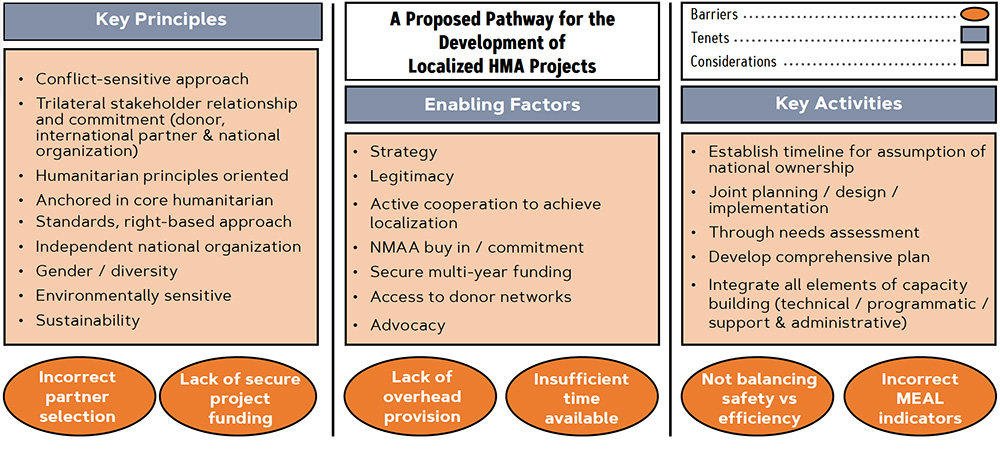

The proposed pathway is built around three tenets: key principles, enabling factors, and key activities. These three tenets might be considered to reflect the necessary project development activities at the inception phase (the key principles), the development phase (the enabling factors), and the delivery phase (the key activities) of HMA projects. Whilst specific risks might be identified at each phase of project design, implementation, and delivery, analysis of the projects delivered thus far by DCA and DRC suggests that a number of specific barriers might be seen to have significant impacts—these are represented here as errors, i.e., activities that if omitted or done improperly, might have significant effect on the overall project outcome.

It is important to note that this model has been developed in an attempt to suggest at least the basics of a comprehensive framework to support future localization project development. It is not intended as a complete instruction workflow, merely as a model reflecting experiential learning from previous DCA and DRC projects.

Conclusions

There is clearly a strong case to be made to support the implementation of localization within HMA activities. Strong commitments have already been made to the localization agenda across broader humanitarian activities and the time is right for the HMA community to both recognize the opportunities that localized responses offer and begin to address the challenges to effective localization that must be addressed. It is evident that there are a number of clear messages that should underpin ongoing discussion and action in furthering the localized HMA agenda:

- Distinction Between Nationalization and Local-ization: Clarify that nationalization of workforces does not equate to localization.

- Design and Analysis: Use conflict-sensitivity analysis to inform the initial design of localized HMA projects.

- Funding Regulations: Advocate for donor procurement regulations that enable direct fund allocation to national actors.

- Capacity Building as Investment: Treat capacity-building activities as a long-term investment essential for successful localization, despite their impact on initial work outputs.

- Risk Management in Localization: Emphasize the importance of risk management, including effective risk identification, ownership, and transfer, as a vital component of effective localization.

The Way Forward

Promoting the commitments made to the Grand Bargain agenda, DCA and DRC believe that localization and national ownership are vital to the effective and efficient delivery of future HMA activities and that localization efforts must be further strengthened. To this effect, we call on states, donors, and organizations with HMA commitments to promote localization, equitable partnerships, and inclusion within the mine action sector by the following means:

States / Donors

- Enhance donor coordination and alignment on localization commitments across the sector via harmonized MEAL frameworks, policies, and funding modalities to ensure overhead coverage and training, as well as promote clarity and shared accountability on risk sharing.

- Encourage the exchange of good practices among states and implementing partners.

- Incentivize the establishment of long-term and strategic partnerships via the provision of multi-year and flexible funding via humanitarian and development channels.

- Establish a standing agenda item at the Mine Action Support Group meetings to discuss localization and national ownership.

INGOs

- Develop organization-wide localization strategies and participate in joint learnings and exchanges of good practices.

- Commit to equitable partnerships and transfer a fair share of their project budgets to national partners, ensuring clarity and shared accountability on risk sharing, as well as committing to work on solid quality management structures.

- Facilitate the participation and exposure of national staff and national partners at international fora for HMA.

- Engage in active consultations with other NGOs to identify and map training and capacity building needs.

- Agree on joint MEAL frameworks to evidence the causal linkage between capacity building, localization, and increased national ownership.

National Actors

- Demand a seat at the HMA decision making fora.

- Join forces to develop and demand for a fair share of funding, including overhead and training budgets.

- Coordinate with INGOs and UN agencies to participate in joint advocacy efforts for localization in mine action vis a vis donors and other international stakeholders.

National Mine Action Authorities

- Facilitate an enabling environment for localization by recognizing the role of local actors in strategic plans and helping to secure any national funding for local mine action actors.

- Play an active role in supporting localized mine action projects.

See endnotes below.

Mark Wilkinson, PhD, has over twenty years of professional experience in the military and humanitarian mine action (HMA). As a former British Army Ammunition Technical Officer, he worked as a high threat improvised explosive device disposal (IEDD) operator in multiple operational environments before transitioning to HMA. In his previous post as the Chief of Operations for United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) in Iraq, he gained extensive experience in developing localization projects for HMA. Dr. Wilkinson has an active research agenda focused around IED clearance in HMA environments as well as localization in HMA.

Mark Wilkinson, PhD, has over twenty years of professional experience in the military and humanitarian mine action (HMA). As a former British Army Ammunition Technical Officer, he worked as a high threat improvised explosive device disposal (IEDD) operator in multiple operational environments before transitioning to HMA. In his previous post as the Chief of Operations for United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) in Iraq, he gained extensive experience in developing localization projects for HMA. Dr. Wilkinson has an active research agenda focused around IED clearance in HMA environments as well as localization in HMA.

Lisa Mueller-Dormann manages the DRC's advocacy on mine action and peacebuilding in Geneva and also serves as the Global Mine Action Area of Responsibility Co-Coordinator as part of the Global Protection Cluster. She has worked on disarmament, peacebuilding, and security sector reform at field- and headquarter-level for the past six years, managing project implementation in South Sudan for DRC and Mines Advisory Group (MAG), as well as for the German Federal Foreign Office in Berlin and the German Development Agency (GIZ) in Addis Ababa. Mueller-Dormann holds a dual master’s degree in international relations and human rights from Sciences Po in Paris and the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University.

Lisa Mueller-Dormann manages the DRC's advocacy on mine action and peacebuilding in Geneva and also serves as the Global Mine Action Area of Responsibility Co-Coordinator as part of the Global Protection Cluster. She has worked on disarmament, peacebuilding, and security sector reform at field- and headquarter-level for the past six years, managing project implementation in South Sudan for DRC and Mines Advisory Group (MAG), as well as for the German Federal Foreign Office in Berlin and the German Development Agency (GIZ) in Addis Ababa. Mueller-Dormann holds a dual master’s degree in international relations and human rights from Sciences Po in Paris and the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University.

Camilla Roberti advises, coordinates, and works on policy, evidence, and learning with a focus on localization and integrated approaches. Prior to her work with DRC, Roberti worked with the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation in Tunisia and the oPt, and DG NEAR and Humanity & Inclusion in Brussels. Through her professional experience, she gained field and headquarter experience in working with local civil society on governance and migration as well as disarmament, peacebuilding, and protection of civilians.

Camilla Roberti advises, coordinates, and works on policy, evidence, and learning with a focus on localization and integrated approaches. Prior to her work with DRC, Roberti worked with the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation in Tunisia and the oPt, and DG NEAR and Humanity & Inclusion in Brussels. Through her professional experience, she gained field and headquarter experience in working with local civil society on governance and migration as well as disarmament, peacebuilding, and protection of civilians.

Lene Rasmussen leads, advises, coordinates, and supports country programs at DCA with resource mobilization, strategy, program development, and management with a focus on humanitarian interventions within a nexus approach. Rasmussen’s experience and expertise has been gained through multiple years of international service on overseas missions in MENA and Central Asia in roles as diverse as regional manager, program manager, grants and finance manager, and logistic manager with responsibilities covering strategic program development and management, fundraising and representation within the HMA and development aid spheres, as well as in monitoring and evaluation and capacity building of local partners, stakeholders, and staff.

Lene Rasmussen leads, advises, coordinates, and supports country programs at DCA with resource mobilization, strategy, program development, and management with a focus on humanitarian interventions within a nexus approach. Rasmussen’s experience and expertise has been gained through multiple years of international service on overseas missions in MENA and Central Asia in roles as diverse as regional manager, program manager, grants and finance manager, and logistic manager with responsibilities covering strategic program development and management, fundraising and representation within the HMA and development aid spheres, as well as in monitoring and evaluation and capacity building of local partners, stakeholders, and staff.