Innovative Finance for Mine Action

Needs and Potential Solutions

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.3 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Danielle Payne [ Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining ],

Camille Wallen, and Chris Loughran [ Symbio Impact Ltd ]

Chronic underfunding has significantly impacted the mine action sector, undermining its stability and predictability. This funding shortfall hampers both the efficiency and effectiveness of operations. This trend is further compounded by the nature of today’s operating environment in mine action; as new conflicts emerge while others are characterized by their protracted nature, the demands on the sector are multiplying. These conflicts not only prolong the threat of landmines but also introduce new hazards, such as the rising use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by non-state armed groups. With the nature of conflicts evolving, the variety of threats grows, necessitating a broader and more adaptive response. Yet, without a significant increase in funding, the sector will continue to struggle to keep pace with these challenges. The mine action community is therefore at a critical point; the sector risks falling irreparably behind unless a holistic commitment to substantial, sustainable support is undertaken.

The recent study “Innovative Finance for Mine Action: Needs and Potential Solutions” published by the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) assesses the current mine action funding landscape.1 This analysis not only details the dire financial needs of the sector but also explores how innovative finance mechanisms, already proven successful in other relevant sectors, could be adapted and applied to mine action. The study provides more broadly an overview of potential solutions that could help to revitalize funding and enable more effective responses to the evolving challenges in mine action. The main findings of this study are outlined in this article.

Introduction

The need for long-term, predictable, stable funding streams has been and will continue to be a recurrent focus for mine action as well as for broader humanitarian aid and development assistance sectors. While the diverse stakeholders in the sector, from traditional donors to those working in mine action recognize the validity of and urgency to fulfill this need, current funding modalities are often limited in their capacity to provide long-term guarantees of support at the fully required funding levels; this is where innovative finance can play a role. Although around for several decades now and initially developed with the aim of accelerating the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals,2 innovative finance remains nascent in the mine action sector. Innovative finance was referenced in Action 42 of the 2019 Oslo Action Plan, yet so far has seen just a handful of small-scale initiatives implemented in Lebanon and Cambodia.

The context in which the sector currently operates is, however, a game changer, creating the enabling environment needed to accelerate innovative finance for mine action. With new and protracted conflicts creating a greater funding need than ever before, funding to mine action is not keeping pace. The sector is faced with the reality that it needs to adapt the way it is funded. To this effect, this article seeks to provide an overview of the current funding landscape for mine action, a brief overview of innovative finance including concrete examples of two innovative finance mechanisms that could be pursued, and recommended next steps for the sector to urgently pursue.

Mine Action Funding Trends and Needs

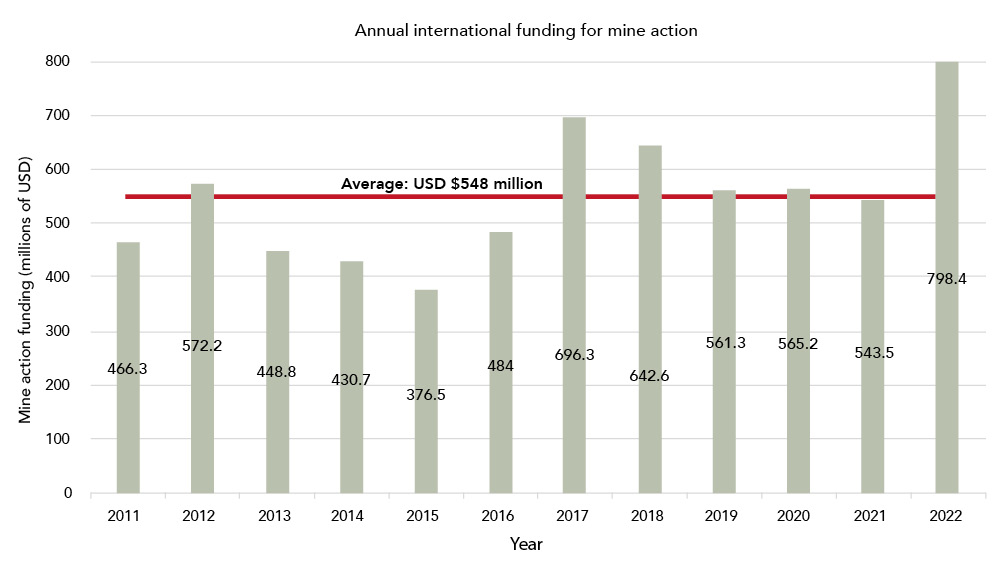

Regarding funding allocations for mine action, there was an all-time high in 2022 at over US$700 million; approximately 20 percent of this funding, however, was allocated for Ukraine alone, with other affected countries receiving funding that was collectively below the levels for 2017 and 2018.

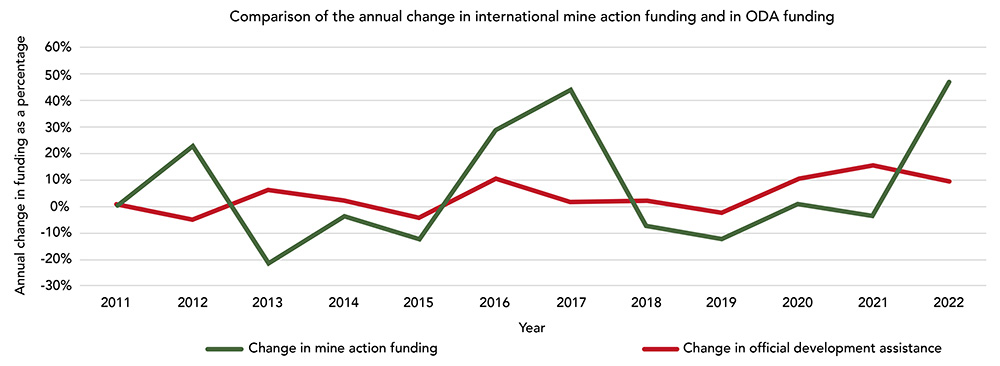

Mine action funding represents a small portion of overall official development assistance (ODA), with annual international mine action funding representing just 0.4 percent of total ODA funding for the period 2011–2022.3 Another notable trend is that mine action funding experiences higher volatility regarding its annual changes than ODA, and experiences particularly short-lived (one to two years maximum) peaks in funding.

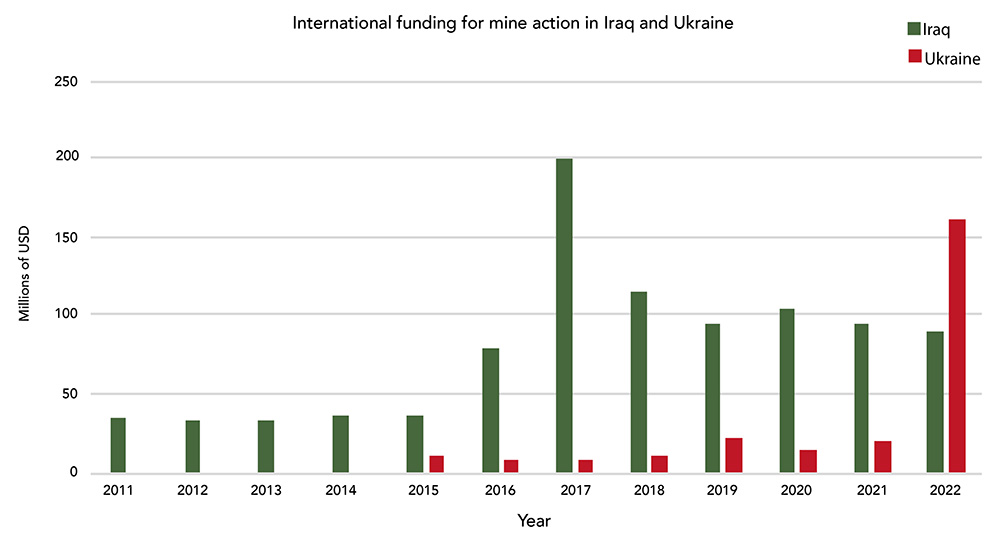

These short-term funding spikes, often influenced by new crises or significant developments in ongoing conflicts, have been witnessed in Somalia in 2012, Colombia and Iraq in 2017, and currently in Ukraine (see Figure 3). These spikes challenge the sector’s sustainability and stability, as countries struggle to effectively absorb and utilize sudden increases in funds. Operations require time to scale up, which means that the intended impact of increased funding may not be achieved during operational adjustment periods. Conversely, abrupt funding cuts, experienced by both those countries from whom funding may have been diverted to respond to a new crisis as well as countries experiencing a new crisis where political interest has waned, force operations to scale down quickly, disrupting planned activities and reducing overall effectiveness.

In terms of funding distribution, while sixty countries and territories are reported to remain contaminated by landmines, between 2011 and 2022, more than 70 percent of the total funding recorded per year went to the top ten recipient countries and territories. Over the same period, each year, the top five recipients—including Iraq, Afghanistan, Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Colombia—received over 50 percent of the total funding.4

Regarding funding sources, the main donors to mine action are primarily governmental donors from high-income countries, including the United States, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. While the donors interviewed in the study acknowledged that the current funding system was imperfect, they also explained the challenges they face, including the need to link mine action to a variety of drivers (such as development outcomes, humanitarian aid, or stabilization). This causes the mine action portfolio to fall under different governmental ministries depending on the specific donor country, which can further complicate coordination amongst donors. Other challenges noted were competing funding priorities, including geographical priorities and government procurement cycles, and budget cycles that can limit funding commitments to the short-term.

Funding needs for mine action were assessed across seventeen mine-affected countries,5 which were selected on the basis that these were the only countries having produced publicly available cost estimates for completing land release commitments under Article 5 of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC). The combined reported cost to fulfill land release commitments for these seventeen countries totals US$1.69 billion. Comparing this estimated funding need with the average annual mine action funding from 2018 to 2022 for these same countries, there emerges an annual shortfall of US$115 million if these countries are to meet their land release commitments within five years.

Furthermore, funding received by these seventeen countries and territories accounted for only 40 percent of the total mine action funding during the same period, with the remaining 60 percent going to countries that had not reported their completion costs. This figure of US$115 million is useful in providing an initial indication of the funding gap based on funding needs communicated by affected countries and territories verses how much funding they are actually receiving. The actual funding gap for the sector as a whole is however undoubtedly much higher; this aforementioned funding gap estimate does not include several highly contaminated states like Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Yemen, which lack detailed cost assessments for completion and for which it is thereby impossible to currently calculate the funding gap.

Why Innovative Finance?

The trends present in the mine action funding landscape demonstrate that while traditional donor funding streams are critical for the sector, they remain insufficient and need to be complemented by other funding sources if the sector hopes to keep pace with the multiplying demands it faces. In addition to addressing the reported funding gap alongside traditional funding mechanisms, innovative finance can create long-term stability and predictability for mine action. This can ultimately help mine action to plan for more efficient and effective interventions that are able to more meaningfully deliver the desired long-term impact.

While no one singular definition exists for innovative finance, the authors of this article have opted to define innovative finance for mine action as initiatives that make use of financial mechanisms to channel public and private funds to help narrow the funding gap for mine action and complement existing funding arrangements in a way that fosters equity, sustainability, efficiency, and effectiveness.

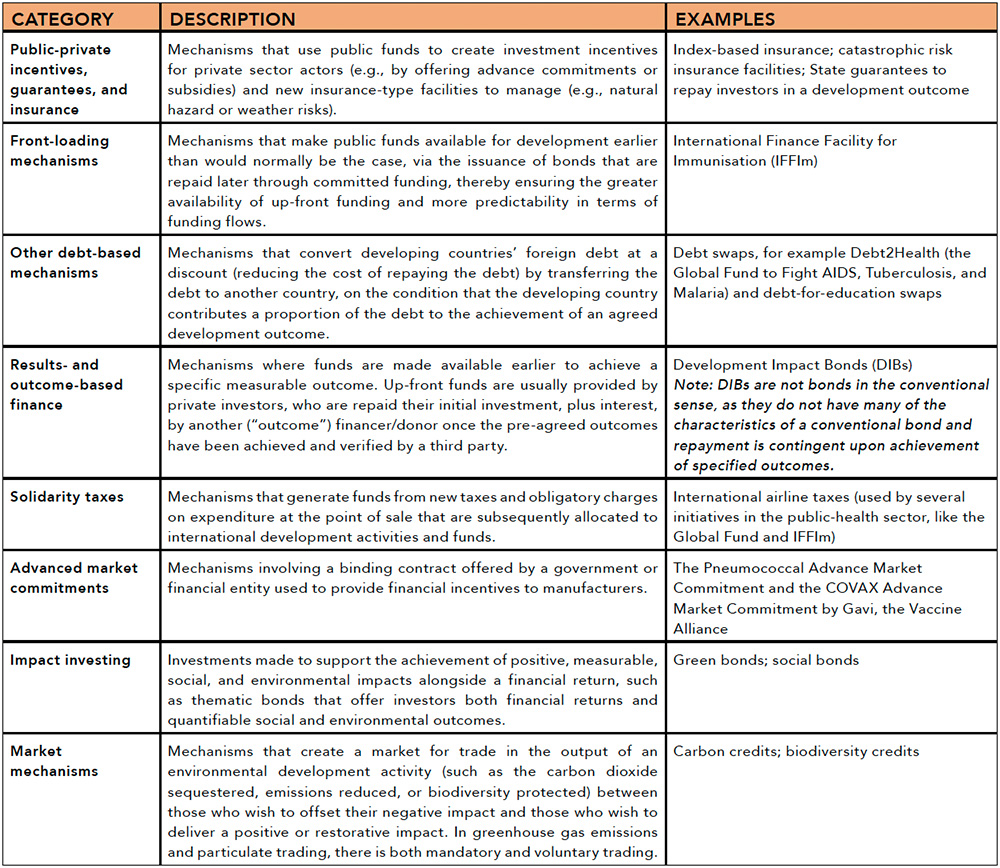

Innovative finance is not a synonym for financial innovation. Innovative finance makes use of a broad range of existing financial instruments and assets. The innovation arises from the application of existing financial instruments to new markets or to involve new investors and mobilize sources of new funding that have not previously been directed to the identified development or humanitarian needs. There are a wide range of potential innovative finance mechanisms used in other sectors that could be applied to mine action, with examples of the main categories provided in Table 1.

The broader study on which this article is based detailed furthermore how two of the categories, as referenced previously, of innovative finance mechanisms that have been successful in other humanitarian aid and development assistance sectors could be applied to mine action: a front-loading mechanism and thematic bonds (a form of impact investing). The application of such mechanisms to mine action will notably require the design and implementation of clear governance structures. These should be developed using an inclusive, cross-sectoral approach, adhere to existing sector principles, and complement existing sector norms, standards, and guidelines.

Mechanism 1: Front-Loading

The front-loading mechanism allows for public funds to be available earlier than they would be through traditional funding mechanisms. It uses long-term, legally-binding government pledges to issue bonds on the capital markets, directing the proceeds to fund the targeted humanitarian or development issue at hand. The main example of front-loading is derived from the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm) approach for vaccines, as shown in Figure 4.

In terms of structure, the front-loading mechanism of IFFIm uses legally-binding, long-term pledges of funding from eleven donor governments, eight of which also currently fund mine action. The funds pledged by these donor governments originate from a variety of sources, some of which can be considered innovative finance mechanisms themselves. For example, the second largest donor to IFFIm, the Government of France, has committed to funding the mechanism in three installments via its Solidarity Fund for Development, which is financed by the tax imposed on air passenger transport between 2006 and 2021, on the model of a solidarity tax, and its Programme 110 budget program, which provides economic and financial development assistance originating from the French Treasury.6

IFFIm uses the World Bank as its treasury manager, which issues bonds based on these long‑term binding commitments from donor governments. This means that the World Bank borrows from private investors and uses the donor governments’ long-term binding pledges to repay the investors their initial investment (principal repayment), along with interest (coupon payment), once the bonds mature at the end of the pre-agreed investment period. The funds raised by the IFFIm bonds are disbursed to immunization programs implemented by Gavi, itself a public-private partnership that brings together a range of actors, including implementing countries, donor countries, UN-affiliated agencies, the World Bank, and private sector partners, and who is the sole recipient of the funds.

In terms of benefits, the use of a front-loading mechanism would essentially enable quicker achievement of mine action goals by allowing donors to “act now and pay later,” crucial for addressing the immediate threats to life and development posed by land contamination. This front-loading approach has accelerated impacts, as seen with IFFIm’s role in vaccinating eighty million more children since 2006 compared to traditional funding methods.

Front-loading also promotes economies of scale and would enhance value for money in mine action. For instance, IFFIm’s vaccine front-loading results in significant savings in healthcare and productivity losses for each dollar spent on immunization. IFFIm equally operates at a global scale necessary for mine action; IFFIm has secured US$9.5 billion in pledges from 2006 to 2023, issuing US$8.7 billion in bonds over the same period. The front-loaded fund disbursements are overseen through an inclusive governance structure that ensures accountability and transparency to both donors and affected states, while providing stable and predictable funding to be drawn down when it is most needed. If applied to mine action, this setup would benefit and empower mine-affected countries by giving them a significant role in fund allocation, enhancing national ownership efforts within the mine action sector.

Mechanism 2: Thematic Bonds

Thematic bonds can come in many different shapes and forms but are also a type of impact investing. This overarching category includes investments made to support the achievement of positive, measurable, social, and environmental impacts alongside financial returns. The establishment of peace bonds7 in the peacebuilding sector constitutes one such practical example of thematic bonds, however no similar instrument exists for mine action today.

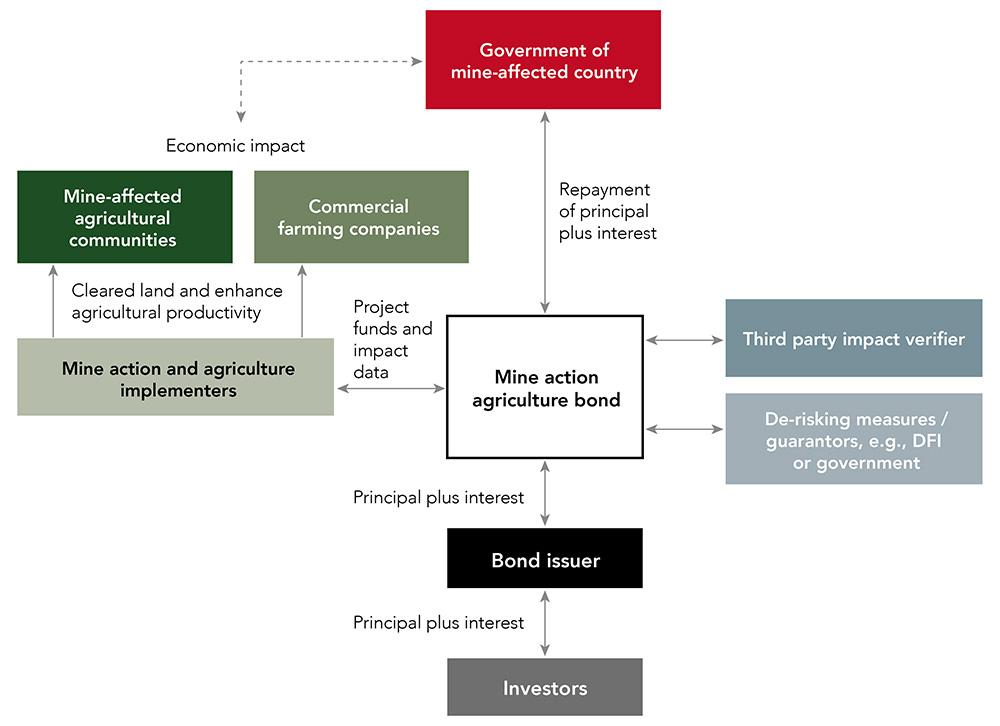

The authors of this article have envisaged the potential development of a mine action agriculture bond as a type of thematic bond that could correspond to the sector’s particular needs.

In terms of structure, this approach involves using bonds to fund land clearance activities that prepare the land for farming. The money invested in these bonds can be paid back through the financial gains from the agricultural activities that take place after the land is cleared. This approach also includes different participants: the mine-affected country, a commercial company, a Development Finance Institution (DFI), or a mix of these entities. They all play various roles in a combined structure that can also include safety nets, such as guarantees from a DFI or a government to reduce risks.

Given the diversity in types of land cleared, the funding from the bonds needs to be organized to support land of varying economic value. More profitable projects might support less profitable ones, which, while not financially lucrative, still reap diverse social benefits. It is furthermore critical to establish clear rules and criteria for the projects and those managing them to make sure that the land clearance does not lead to negative outcomes like land theft, increased conflict, or the exclusion of certain groups.

Having a third party verify the results of the projects funded by the bonds is considered best practice. This ensures accountability and transparency for all parties involved. This verification should enhance and utilize the existing monitoring and evaluation efforts by national authorities responsible for mine action.

In terms of benefits, a mine action agriculture bond could strengthen and advance development outcomes. Such outcomes can be further enhanced when additional criteria are set for agriculture projects eligible to be covered under the bond (such as being engaged in sustainable, environmentally friendly agricultural practices). This mechanism can also reinforce national ownership, with the mine-affected country or territory at the center of the mechanism, and ultimately reduce reliance on ODA. Such a mechanism should also be tailored to the country’s or territory’s specific needs.

Conclusion

Overall, a range of innovative finance mechanisms that are complementary to traditional funding mechanisms have proved themselves effective when applied in other humanitarian aid and development assistance contexts. Such mechanisms can and should be explored for the mine action sector, particularly the front-loading mechanism, which operates at the scale needed to address the significant funding gap across the sector.

The political will to develop large-scale innovative financial mechanisms has also been identified as a critical requirement. The current context in Ukraine provides the mine action sector with a moment of opportunity; given that funding needs and political interest are so high, they could prompt the exponential increase in awareness of and appetite for the application of innovative finance mechanisms to mine action at the global level. The recent roundtable “Developing a Front-Loading Mechanism for Mine Action”8 demonstrated interest from both mine action and external actors (including several of those who developed and launched the front-loading mechanism for IFFIm) to harness front-loading’s potential for mine action.

While the sector’s current focus on Ukraine may help feed the overall appetite, innovative finance solutions must continue to be sought for all interested affected countries and territories, the funding needs of which are equally important. The future of mine action needs innovative finance, and there is a critical role as well as dire need for collaboration across various sectors.

In terms of recommended next steps, the article’s authors have anticipated three main areas of effort:

Develop an enabling framework to drive innovative finance for mine action: This includes ensuring all relevant mine action stakeholders, including for example national mine action authorities, operators, and donors, are informed about innovative finance solutions and are engaged in complementary efforts to help collectively drive this work forward. This would include, for example, having more comprehensive, reliable data from affected countries and territories on funding needs; advocating for more consistency in donor reporting (including from private and philanthropic donors) on annual funding for mine action; and mainstreaming guidance on innovative finance in relevant on-going capacity enhancement efforts in the sector.

Develop agreed principles and guidelines for the governance and implementation of innovative finance within the mine action sector: Prioritizing transparency, inclusiveness, and accountability is paramount for this endeavor. This should furthermore make use of existing good practice and relevant guidance from diverse sectors, including for example guidelines for environmental, social, and governance investment, humanitarian principles, and the International Mine Action Standards.

Systematically and transparently engage with the private sector and international finance institutions (IFIs): Collaboration with the private sector and IFIs are essential for the successful development and implementation of innovative finance mechanisms. Extensive outreach and exchange, including making the effort to “speak the language” of the private sector, is crucial for all stakeholders within mine action.

The authors would like to conclude this article with a call for action to the mine action sector as a whole—join us in this effort to advance innovative finance for mine action and ultimately develop impactful solutions from which we all, and particularly all those that we serve, will be able to benefit.

To access the full study, “Innovative Finance for Mine Action: Needs and Potential Solutions,” please visit https://bit.ly/4cadp0w.

See endnotes below.

Danielle Payne joined the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) in February 2022, and currently works as Mine Action Programmes Coordinator. In this role, she leads the GICHD’s work on innovative finance while also working with the Chief of Mine Action Programmes to support the coordination of efforts and continued development of the Mine Action Programmes Directorate at the GICHD. She provides support on matters related to institutional development, donor relations, and partnerships with diverse stakeholders. Prior to joining the GICHD, Payne worked for the International Organization for Migration in Côte d’Ivoire with a focus on cross-cutting program support, border management, and counter-trafficking. Additionally, she worked in emergency preparedness for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She holds a Master of Arts in International Relations from the Université Jean Moulin in Lyon, France and a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies from the State University of New York at Cortland.

Danielle Payne joined the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) in February 2022, and currently works as Mine Action Programmes Coordinator. In this role, she leads the GICHD’s work on innovative finance while also working with the Chief of Mine Action Programmes to support the coordination of efforts and continued development of the Mine Action Programmes Directorate at the GICHD. She provides support on matters related to institutional development, donor relations, and partnerships with diverse stakeholders. Prior to joining the GICHD, Payne worked for the International Organization for Migration in Côte d’Ivoire with a focus on cross-cutting program support, border management, and counter-trafficking. Additionally, she worked in emergency preparedness for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She holds a Master of Arts in International Relations from the Université Jean Moulin in Lyon, France and a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies from the State University of New York at Cortland.

Camille Wallen is Co-Founder and Director of Symbio Impact Ltd and Co-Founder and Global Head of Mine Action Strategy and Funding Innovation of the Mine Action Finance Initiative. She has over twelve years’ experience working with the mine action sector, most recently as director of strategy for The HALO Trust until 2022. She has pioneered the exploration of large-scale innovative financing solutions for the mine action sector. Her experience is in senior leadership, developing and delivering complex organizational strategy, impact monitoring and evaluation, development finance, and resource mobilization strategies. Wallen has lived and worked across Europe, South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America and holds a Bachelor of Arts with Honors and a Master of Science in International Development Economics from the University of Bath.

Camille Wallen is Co-Founder and Director of Symbio Impact Ltd and Co-Founder and Global Head of Mine Action Strategy and Funding Innovation of the Mine Action Finance Initiative. She has over twelve years’ experience working with the mine action sector, most recently as director of strategy for The HALO Trust until 2022. She has pioneered the exploration of large-scale innovative financing solutions for the mine action sector. Her experience is in senior leadership, developing and delivering complex organizational strategy, impact monitoring and evaluation, development finance, and resource mobilization strategies. Wallen has lived and worked across Europe, South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America and holds a Bachelor of Arts with Honors and a Master of Science in International Development Economics from the University of Bath.

Chris Loughran is Co-Founder of Symbio Impact Ltd and Co-Founder and Global Head of Mine Action Governance at the Mine Action Finance Initiative. He has over twenty years’ experience in the not-for-profit and public sectors, including at senior leadership levels. His expertise is in disarmament processes, mine action policy, and diplomacy. He has extensive experience in strategy governance and organizational change, policy and public affairs, and income diversification involving the private sector. He specializes in the development and implementation of policy, advocacy, and campaign strategies that inform decision makers and influence positive change. Loughran has lived and worked in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and worked extensively in Asia. He holds a first class degree from the University of Oxford and a master’s degree from the School of Oriental & African Studies in London.

Chris Loughran is Co-Founder of Symbio Impact Ltd and Co-Founder and Global Head of Mine Action Governance at the Mine Action Finance Initiative. He has over twenty years’ experience in the not-for-profit and public sectors, including at senior leadership levels. His expertise is in disarmament processes, mine action policy, and diplomacy. He has extensive experience in strategy governance and organizational change, policy and public affairs, and income diversification involving the private sector. He specializes in the development and implementation of policy, advocacy, and campaign strategies that inform decision makers and influence positive change. Loughran has lived and worked in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and worked extensively in Asia. He holds a first class degree from the University of Oxford and a master’s degree from the School of Oriental & African Studies in London.