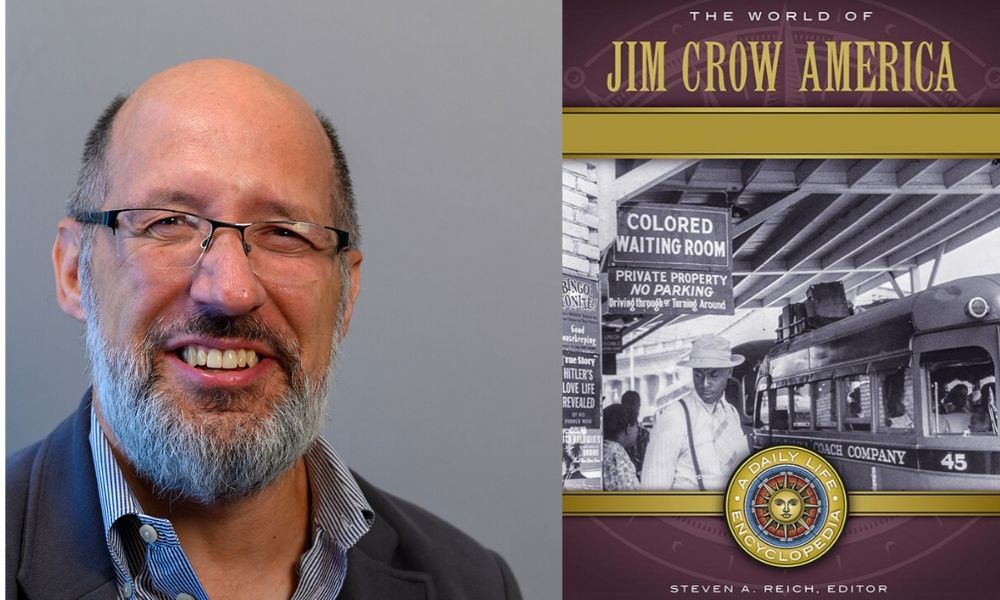

History professor Steven Reich publishes encyclopedia on Jim Crow America

Research

After completing a Ph.D. at Northwestern University, Steven Reich joined the JMU Department of History in 1999. An expert on American labor history and African American history, Reich teaches a variety of courses, including: African American History since the Civil War, the American South since the Civil War, American Working Class History, a U.S. History Survey, and the General Education Cluster One course -- Critical Issues in Recent Global History.

Director of Research Development & Promotion, Ben Delp, sat down with Professor of History Steven Reich for a conversation about his new work -- The World of Jim Crow America: A Daily Life Encyclopedia.

R&S: You recently served as Editor for The World of Jim Crow America, which covers the social, political, and material culture of America during the Jim Crow era. What is the Jim Crow era and when did it happen?

Reich: Jim Crow is a colloquial term for segregation in the United States – racial segregation, legalized racial segregation – roughly a period from the late 1880s until the Civil Rights Movement. Another word for segregation in a way is the phrase “Jim Crow Laws,” so these were the laws that would segregate black people in southern states in public spaces, for example, trains, street cars, buses, waiting rooms, restrooms, drinking fountains, jails, cemeteries, balconies in movie theaters and playhouses, and telephone booths. It was particularly an urban phenomenon. Because there’s more public space in a city there’s more public space to segregate. When buses replaced street cars, the buses carried the segregation. When airplanes were introduced and you had airports constructed in the South, they were segregated as well. They even had Jim Crow Bibles, so when African Americans had to swear in a Court of Law they had special bibles. One of the things about Jim Crow Laws was that not only were they meant to segregate or separate certain waiting areas and dining areas, but these were intended to keep white women away from black men. Some historians have pointed out that the more likely that a public space was to be integrated by sex, the more likely it was to be segregated by race. Single-sex places tended to be less segregated – coal mines and male workspaces.

There are other laws that go along with Jim Crow. These are the laws that exclude African Americans from participating in politics through eliminating their access to the vote. We hear the phrase voter suppression today. The classic period of voter suppression is the Jim Crow era, when southern states passed statutes or revised their state constitutions in order to exclude certain people from having access to voting. To register to vote you had to pay a poll tax or you had to demonstrate your literacy, that you understood a particular reading passage, and this was often done just to intimidate people from voting. They were not racially specific because that would have been an overt violation of the 15th Amendment, but they had an unmistakable racial intent and an unmistakable racial outcome. Certainly white people who did not pay their poll tax wouldn’t have been able to vote, but the understanding test was much easier for white people than it was for black people. And of course, one of the principal sites of racial segregation was schools, public education.

With respect to the name – Jim Crow – the volume’s introduction explores its origin: “The term ‘Jim Crow’ originated from a popular nineteenth-century minstrel show created by the white playwright and entertainer Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice (1808–1860). Rice invented the persona of Jim Crow, a groveling, comical, and simple-minded plantation slave, whom he featured in hundreds of song-and-dance routines that mocked and caricatured the dialect and behaviors of blacks. In the post–Civil War years, the Jim Crow character became the icon of segregation whose image embodied white America’s demeaning attitudes toward black people. Jim Crow was thus the very servant of society that Frederick Douglass feared and as such was a fitting term for the social, cultural, economic, and political subordination of African Americans.”

R&S: Why did you choose to examine this time period of American history?

Reich: It’s a period that I’ve done my own scholarship in, particularly African-American working class history. I’ve always been interested in the both the long-term legacies of Jim Crow and also the ways in which people resisted and fought against Jim Crow – how people acted politically in a world that denied them access to formal politics. I had completed a similar project for Greenwood Press several years ago, a multi-volume reference work on the great black migration of the 20th century, and they encouraged me to take on this subject matter. One of the nice things about a project like this is that it enables me to have to catch up on scholarship. I have to think about what are the different entries that are going to be covered in a Jim Crow daily life encyclopedia, and then I have to find out who are some new scholars and what is the recent scholarship on the period. When I started the project, I was on educational leave, and I was able to use the time to conduct the research necessary to design to the volumes and to identify the topics that I wanted covered and the scholars whom I wanted to contribute to the project. This is also the kind of the work that helps to infuse my classes with new material.

R&S: As you stated, this work connects with your scholarly interests and past publications. Given this is not new territory for you, was there information that you discovered that you were unfamiliar with or that surprised you?

Reich: The series itself is daily life, so the structure of the volumes have these categories, and I had to populate each category with topics. You have arts, economics and work, family and gender, fashion and appearance, food and drink, housing and community, politics, warfare, recreation and social customs, religion and belief, science and technology. I was pretty familiar with most of these topics, but fashion and appearance and food and drink I knew very little about. That got me reading and familiarizing myself with scholarship that I had very little knowledge of – cookbooks, canning, moonshining, restaurants and cafes, bars and bartenders, cooks themselves, and then beauty pageants, beauty salons, and the way in which clothing and dress shaped racial identity, the ways in which whites expected blacks to dress in a certain way, and the ways in which blacks fought against that by trying to fashion their own identities through their own creative use of dress. Those were things that I realized I knew very little about, and that I will make more central to when I teach African American history in the spring semester.

The volumes have an appendix of about 40 primary sources. Some of the interesting things I discovered were great sports pages in some black newspapers in the very early 20th century, the ways in which black newspapers advertise their own kind of beauty pageants and beauty shows.

This research provided me with access to interesting things that I wouldn’t necessarily encounter in my studies of workers and political activists.

R&S: Who should read this work? Students, academics, those who might not be all that familiar with the Jim Crow era and its impacts?

Reich: It’s largely intended for students, student researchers, and it should have a place in public libraries, college libraries, and high school libraries. The hope is that students doing research or trying to familiarize themselves with this period while looking for topics, that this is a place to start – provide an overview of the topic and then point you to further reading to go investigate. Additionally, I could imagine other scholars going to this work when in need of a quick orientation. For example, I have to give a lecture on disenfranchisement laws and I need a quick orientation. The essay on disfranchisement laws will give you the basics you need to know to be conversant when walking into the classroom.

R&S: As a historian, you probably recognize patterns of societal behavior over time, and that many present-day issues are not unique to our current era. Our politics are hyperpolarized and there seems to be increasing levels of anger and distrust in our political discourse. Can history as a discipline provide us some perspective, and potentially some strategies or examples to improve our current state of affairs?

Reich: Absolutely. The Jim Crow period should alert us to the consequences of a society that consciously excludes talent from access to wealth, opportunity, governance, and the ability to contribute to the life of society. It impoverishes the entire nation. When we see our political leaders arguing for voter suppression, when we see political leaders arguing for exclusion of people of different races and ethnicities, sexual orientations, wanting to ban people of certain dispositions from the workplace or in the military, we can look to the Jim Crow period. What did the United States look like when the United States consciously and overtly did this by law?

One of my favorite historians has a line from one of her books that has always stuck with me – The Jim Crow period was a colossal waste of talent. When you read in the Jim Crow period you find all kinds of men and women of talent who were Black, who because of the law could not go to medical school, could not go to law school, could not get loans, could not buy houses where they wanted, could not be promoted at work, could not vote, could not sit on juries, could not contribute their insights to the making of our laws, and that impoverishes the whole. If we want to look at the consequences of mass exclusion – that was Jim Crow America.

R&S: Thank you for sharing information about this important work. What’s your next research project?

Reich: I have a couple projects that I’d like to finish. One is a story about black land loss, and another is about a riot in the south that has virtually no scholarship, also about black land loss. It happened in 1910 in a rural area of Texas. Several hundred black residents were basically wiped out or banished from the southern part of the county. I have some things to say about these events that I haven’t finished saying. Rather than do another work where I'm editing other people's work, I want to write my own scholarship.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Access the condensed interview