Harnessing the potential of AI

Artificial intelligence’s potential to spark fear and confusion can easily overshadow its potential for improving lives

Featured Stories

SUMMARY: Philip Frana, professor of interdisciplinary liberal studies and independent scholars, says “the notion that there is a fixed amount of work to do and that AI will inevitably lessen demand for human employment ... is one of many ways in which AI is being misunderstood.”

|

|

It’s a common refrain in media portrayals — the idea that artificial intelligence will take our jobs. As the field of AI makes significant progress and achieves landmarks of historic importance, its potential to spark fear and confusion can easily overshadow its potential for improving lives. The so-called “lump of labor” fallacy — the notion that there is a fixed amount of work to do and that AI will inevitably lessen demand for human employment — is one of many ways in which AI is being misunderstood. Despite the rapid uptake of AI by a broad swath of industries and subfields, there remains considerable media fearmongering about AI. It has become a scapegoat for nearly every cultural anxiety, from inequality to apathy. Some commentators even suggest the dislocations between humans and their jobs will be so great that we will need to implement a universal basic income for vulnerable people. This is one of many reasons it’s important to educate on the topic of AI. To prepare students for a changing world, we must foster truth and dispel unfounded fears.

Fast track to the future

AI is having a very busy year, with significant growth occurring along many of its branches. Most notable are achievements in the subfield of generative AI, which uses artificial neural networks to identify patterns and structures within collections of information, as well as train machine learning models and create artificially generated text, code, art, music or video. These machine learning models are rapidly becoming the engines for addressing real-world problems. Dozens of companies and nonprofits are launching a wide range of applications with generative AI, from question-answering services and conversational chatbots to text-to-image generators and computational creativity tools. In only two months this past spring, ChatGPT reached 100 million monthly active users — an astonishing show of how quickly large language models can transition from blackboard concepts to practical applications. Today, much of the alarm surrounding AI perpetuates sensational narratives, unrealistic predictions and past overpromising. The bugaboos of AI — given ominous labels like “unfriendly AI” and the “control problem,” “paperclip maximizers” and “gray goo,” “artilects” and “terminators” — bear striking resemblances to our most ancient fears of fiendish monsters and apocalyptic catastrophes. Besides the threat of lost jobs, superintelligence has been a hotly debated topic in the media, perpetuating a fringe scientific notion about machines becoming conscious and out-witting humanity. Regrettably, the most sensational claims about AI as some kind of “final invention” of humankind have spread like wildfire. Elon Musk famously likened AI to “summoning the demon,” while Stephen Hawking once warned it “could spell the end of the human race.” For now, however, creating an AI that reaches general human intelligence, let alone superintelligence, remains out of reach. For more than a century, Americans have worried about automating themselves out of jobs and similar robot-induced indignities. However, the great majority of AI developers offer a more optimistic and hopeful message. They argue that AI will create new job opportunities, increase human productivity and lead to growth in traditional and creative industries. Will jobs disappear? Yes. McKinsey & Co. estimates that 400 million to 800 million jobs are at stake in the current round of workplace automation around the world. History shows that technology has led to substantial changes in employment and industries, but also creates new sources of labor demand. College graduates are landing entry-level jobs as labelers who train AI to understand data sets by categorizing source information and as fairness auditors who provide feedback on machine learning architectures to reduce the likelihood of biased outcomes. Additionally, prompt engineering involves designing and testing prompts for virtual assistants and other generative AI tools. Prompt engineering is so new that, as recently as this summer, OpenAI’s famous generative pre-training transformer chatbot, which scours the internet for information that will answer user questions, knew nothing about it.

A history of AI

Taking the long view is crucial when evaluating the usefulness of AI. No fewer than three generations of AI researchers have come and gone since John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester and Claude Shannon convened the first workshop on AI in the 1950s. In several ways, the first generation bears the closest intellectual kinship to the current crop of researchers. They were the pioneers who hoped to simulate the brain’s organic processes and neural pathways, but they had limited computational power to achieve their ambitions. The second generation coded ingenious symbolic and statistical AI systems. These engineers of knowledge-based expert systems had success in narrow specialties.

But companies founded in the 1980s failed to make money, and enthusiasm dwindled. Today’s generation of developers, having abundant computing resources and massive pools of public and private data at its fingertips, has revived neural network models reminiscent of those in AI’s earliest conception. Great leaps are being made in deep learning, a particular branch of machine learning that involves training interconnected layers of artificial neurons that mimic the agile and adaptable architecture of the human brain. The large learning models and transformer architectures prominently featured in popular media represent just one of the many breakthroughs in generative AI.

Working toward progress

The declared purpose of AI is to support human capabilities by building software and hardware tools that can imitate human cognition and behavior. AI programs are already embedded in various common technologies, and AI developers are constantly focused on identifying patterns in the world and making models that are useful to accomplishing difficult tasks. Consumer AI software can play competitive chess or translate languages. Helpful virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Google Assistant depend on AI algorithms, as do personalized recommender systems in video streaming apps, such as Netflix and YouTube. Some applications, like fraud-detection software, medical image tumor detection (radiomics) and continuous glucose-monitoring systems, exemplify vital technologies by playing mission-critical or life-preserving roles. In research labs, AI is being adapted to make anti-terror surveillance cameras, turn smart TVs and mobile devices into personalized digital advertising ecosystems (LensAI, Equativ), and aid in the decoding of ancient languages (Ugaritic and Linear B) and animal communication (Earth Species Project, Project CETI). PwC, also known as Price Waterhouse-Coopers, estimates that within the next seven years, AI technologies alone could contribute $15.7 trillion to the global economic bottom line. Yet, for all that AI can do, there’s still a lot that we don’t know how to facilitate yet. The dream of some research groups and companies is to use deep learning to create artificial general intelligence, the sort of adaptable, meaning-making intelligence possessed by humans. Smart robots are getting better at running assembly lines and sorting packages, but the most optimistic timetables for AI innovation have not been achieved. For instance, predictions of full autonomy for cars and trucks on the open road by the 2020s remain unrealized. Instead, we are seeing more semi-autonomous technologies in human-monitored environments, such as sidewalk delivery robots, geofenced taxi services and automatic coal trains. Giving AIs the ability to seamlessly move among us and interact effortlessly, like androids do in science fiction, is going to be difficult. For now, it’s been useful for programmers to focus on ways that AI can excel in our current society and how people can benefit most from AI assistance. There is a growing consensus that the kinds of work people perceive as easy — or imagine is very hard — may be exactly the right tasks to automate with AI. The sweet spot in the future of work is where artificial and natural intelligence, creativity and compassion, harmoniously intersect — such as occupations like counseling, social work, nursing, peace-making and environmental conservation. In a world with ubiquitous AI, those who dedicate their lives to helping people and nature will become ever more invaluable.

Photograph by Elise Trissel

AI’s critical importance

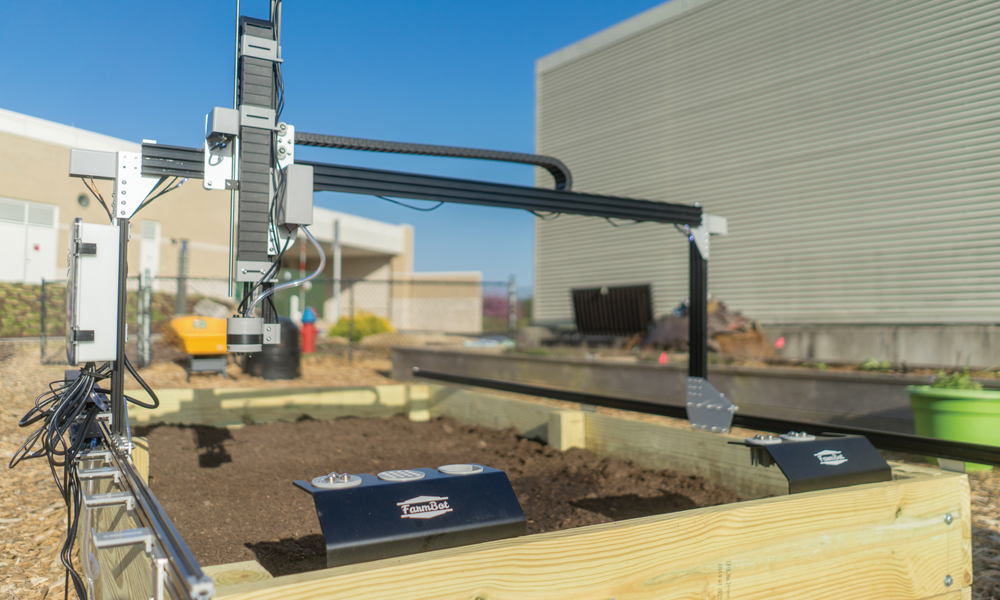

As the world urgently needs smarter technologies, AI is becoming increasingly crucial. The human need to efficiently analyze vast troves of data has never been greater, and AI can play a significant role in managing our information-based society by generating valuable insights and enhancing decision making capabilities. AI technology also holds the potential to improve our judgment at critical moments and support us in thinking more strategically, even when we lack the bandwidth to do so. Additionally, AI can address some of the shortcomings of smartphone and internet use. It can find important patterns in data we cannot see or hold in our heads when we passively scroll through websites and social media posts. Imagine if an electronic helpmate observed what we say and do, then whispered in our ear and gave us great advice. Despite its many benefits, AI will have disproportionate impact in some areas, like in sustainability, entrepreneurship and education. It can help environmentalists apply smart technologies to create an ecologically sensitive circular economy, allowing AI to identify intricate patterns of material and energy flow in complex systems of production and suggest action plans for eco-conscious resource extraction, materials use, recycling and nature restoration. In business, collaborative robots (“cobots”) are working with humans to handle high-volume and tedious tasks, improve quality control, and predict maintenance schedules and inventory bottlenecks. Smart computing in agribusiness is optimizing crop yields, reducing water and chemical usage, and improving market delivery schedules. Machine intelligence is being used to create a marketplace for behavioral prediction products that analyze human attention and engagement, anticipate human behavior, and design personalized goods and services. We can also expect to see major changes in how organizations manage human resources, customer support, and budgeting and visioning in the age of AI.

|

|

Historically, the technical feasibility of automating education has been low and for good reason. Education is one of the most human of endeavors; it certainly involves more than assignments, testing and grading. Good learning — the kind that sticks with us and shapes our character — requires social interaction, adaptation and development of future-proof skills like critical thinking, empathy and ethics. Until recently, it was assumed that no machine could teach strategies for conceptual thinking, creativity or judgment. And, as of 2021, an EDU-CAUSE quick poll of institutional leaders, IT professionals and other staff found that only 12% had contemplated the use of intelligent-teaching systems in their work. However, the landscape of education has shifted, and the impact of AI on learning could exceed that of every other service sector. There are immediate opportunities for using AI chatbots in higher education admissions, advising, tutoring and mental health support. Certainly, homework will never be the same. Today, tens of millions of students are learning to use personalized and adaptive “intelligent education” platforms like ALEKS, Squirrel, MATHia, Duolingo and Toppr. Perhaps even more radically, AI will change the way we close access and completion gaps, make higher education affordable, and promote global awareness. This past summer, Emad Mostaque, a prominent figure in open-source AI, announced a project aimed at training adaptive learning models for use as “intelligent tutors” for children in Malawi, where rates of literacy and numeracy remain stubbornly low.

Photograph by Olive Santos (’20)

Ethical and civil obligations

AI technology should not be viewed as a herald of bliss or portent of doom. More probable is a middle path of moderately accelerated transition, innovation and change. The development of AI is also not like the making of the atom bomb; it is fundamentally different in nature, purpose and contextual circumstances. The scientists of the Manhattan Project determined that their efforts were necessary to turn the tide of World War II and identified some of the ethical questions related to its devastating power. Scarcely could they imagine that their work would unleash human productivity, and only later did political leaders fully recognize the potential of “atoms for peace.” This is not to say there are no moral or existential implications of AI. Among the concerns are implausible visions of post-scarcity societies, simulated realities, artificial oracles and a technological singularity that fundamentally alters the material basis of civilization. In the near future, the chief dangers of AI technology are pervasive but subtle risks like bias, misinformation, over-optimization, weaponization, practical de-skilling and harm to human uniqueness, privacy and accountability. We need to reflect and make changes now to ensure a successful future with AI. What could AI mean for democracy, economic well-being and civic engagement? The application of AI in the creation of more responsive and stakeholder-centered governance could become a hallmark of our national development plans. An emphasis on serving the public interest ensures that AI solutions will align with people’s needs. Public-private collaboration focused on combining AI resources, expertise and other capabilities will safeguard the nation’s adaptability as economic, political and intellectual marketplaces continue to change. Universities will need to work closely with the private sector to meet the state’s specific needs for AI infrastructure, workforce development, startup culture and technology adoption. AI’s value lies in empowering humanity with tools that extend physical and mental capabilities while mitigating risks and hazardous situations. They can improve quality of life, promote economic prosperity and cultivate eco-friendly habits. Americans should consider embracing the most remarkable aspects of artificial intelligence as a paradigm-shifting “cultural technology” — a novel set of powerful, creative tools for transmitting our collective wisdom, expressing civil liberties and advancing prosperity.

|

|

AI for Good — a recent call to action for teachers, students, entrepreneurs and public officials — requires a multidisciplinary human effort. AI draws knowledge and inspiration from mathematics, computer science, psychology, biology, economics, education, political science, linguistics and philosophy. Creative AI initiatives worldwide are fostering collaborations across an even more diverse range of fields and vocations. These initiatives will offer meaningful opportunities for people keen to comprehend the problems, patterns, and complexities of cities and regions. In this way, everyone can become producers, consumers and users of new AI technologies. Human beings should worry less about an “AI takeover” and instead address the immediate consequences of AI, which have everything to do with ordinary human tendencies — like making our society and economy too brittle by excessive streamlining, endangering our lives through military aggression, and creating attention-grabbing platforms for mass distraction that prioritize profit over human fulfillment. Ultimately, AI is a mirror reflecting human nature. When we worry about positive and negative AI outcomes, we are really thinking about our own redeeming and destructive capabilities. When we ask if an AI is intelligent, creative or dangerous, we are really asking those things of ourselves.