Overcoming great odds, refugee alumnus imagines a greener future

Entrepreneur Tan Nguyen (’92) pioneers food-waste solution

Featured Stories

SUMMARY: An innovator in food-waste recycling and distribution, Tan Nguyen’s (’92) journey is a powerful testimony of resilience, perseverance and adaptability.

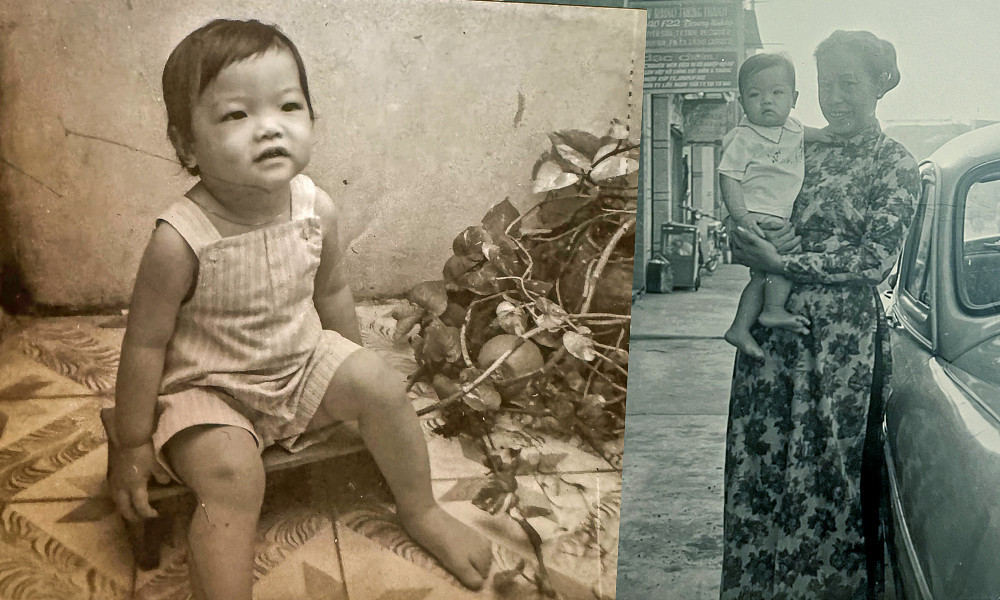

Tan H. Nguyen (’92) relies on cultural memory to paint a picture of his earliest years in South Vietnam during the 1970s.

“The collection of these stories that my mom and aunts would tell me was always filled with a lot of fun and a lot of love,” he said. “It wasn’t until close to the fall of Saigon, when it was chaotic, that there was uncertainty.”

As North Vietnam’s communist regime progressed further into the south, those opposed to the movement risked political imprisonment or death. Frantic and facing the possibility of great suffering, Nguyen’s mother decided to flee with Nguyen and his siblings aboard a cargo ship to Guam in 1975.

During the fateful journey to America at age 5, Nguyen’s full memories locked in. “To be whisked away on a boat, find our way to an island, all of a sudden be in this giant tent city with thousands of people waiting in line for each meal and then working toward placement in the U.S. into a refugee camp — for a child, that was very confusing,” he remembered.

|

“Wherever I go, whatever I do, I’m aware that I represent JMU.” — Tan Nguyen (’92), entrepreneur and CEO |

Starting from zero

After a lottery system relocated his family to Pennsylvania, Nguyen witnessed his single mother struggle to integrate into a new country with a foreign language. In Saigon, she had worked as a bank teller and was fluent in Chinese and French; in America, she supported the family through odd jobs, such as cleaning houses and altering clothing.

Nguyen’s generation of immigrants grew up in an environment where their parents came from nothing, stripped of previous education and trades, and built livelihoods in the face of racism. “And in my mom’s case, sexism,” he said.

“There was a backlash of hatred toward Vietnamese refugees, because a lot of people in America did not like the idea of the Vietnam War. I watched the refugee adults bear that weight from society, but they were resilient. They continued to push forward and work harder. They continued to be creative, and they were persistent about it.”

For the rest of his youth, the message of resilience and perseverance stayed with Nguyen. “There’s nothing I can’t overcome — you just gotta work harder. There’s nothing beneath you — be grateful,” he said. “Being a refugee of the war molded a big part of who I am.”

A welcoming atmosphere

As a member of a low-income minority group, Nguyen qualified for the Milton Hershey School in Pennsylvania, founded in 1909 by chocolatier Milton S. Hershey and his wife, Catherine. Nguyen spent four years at the cost-free, private boarding school, where he experienced the power of compassion and philanthropy firsthand.

But it was at JMU where Nguyen felt at home. He applied as a transfer student from Old Dominion University and was accepted in 1989. “I wanted to be part of this legendary, mythical place in Harrisonburg that everyone kept talking about,” he said. “I worked hard my freshman year to make sure I stood out and could make it to JMU.”

“I felt so welcomed,” Nguyen continued. “The culture of JMU was everything I thought it was going to be — the staff, incredible professors, student body.”

At first glance, Nguyen’s resume and career resembles the path of a College of Business graduate. His six-year stint at Sprint telecommunications during the early 2000s led to the acquisition of two startups at the forefront of wireless technology. In 2007, he took a calculated risk, establishing his own multimillion-dollar mobile media company: NuWin Enterprises. His most recent venture, NuWin FWRD (Food Waste Recycling and Distribution), focuses on reducing food waste and methane gas from landfills.

A closer look into what drives the serial entrepreneur and CEO reveals a self-proclaimed “fascination” with human behavior. Without hesitation, Nguyen pursued a Psychology degree at JMU. “Psychology is a thread through everything, especially business,” he said. “If you don’t know your consumer, if you don’t know behaviors, you cannot provide that customer with what they’re looking for.”

“In business, we’re dealing with all kinds of personality types that have different agendas, needs and wants,” said Nguyen, a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon. “My Psychology major is counseling applied in the real world that gets a result, where everyone is participating in this mission of trying to clean up the planet.”

While he was raised to persevere and practice resiliency, Nguyen credits his Madison Experience with directly shaping the third quality of his personality: adaptability. “At JMU, I was put in an environment that was diverse and inclusive,” he said, explaining that this dynamic fosters a “growth mindset” — a key component of being an effective leader and successful businessperson. “When we have a growth mindset, we’re adapting to the world as it evolves, and we become part of the solution.”

Closing the loop

With the gift of adaptability comes the ability to examine a traditional model and change it for a better future. As a parent, Nguyen realized designing apps wouldn’t improve the Earth for his daughter. A personal journey in 2015 led him to pivot and question the state of garbage in America — an economic opportunity to innovate the landfill.

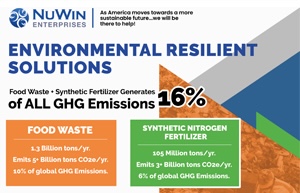

“When I looked into climate change, the narrative was dominated by electric vehicles and renewable energy,” Nguyen said. “What I discovered was the third-largest culprit of greenhouse-gas emissions was food waste, and no one was talking about it.”

Globally, humans discard 40% of all food produced, and food waste remains the largest, single product in a landfill. Once the food is tossed in the trash bin or goes down the garbage disposal, Nguyen says it’s part of the “throwaway” culture not to worry about where the waste goes next.

Launched from the social sustainability efforts of NuWin Enterprises, NuWin FWRD patented an enzyme-based formula that accelerates nature’s decomposition process. Composting takes three to four months before it is used as fertilizer. Nguyen’s thermal aerobic digestion technology can break down 5 tons of food waste in 24 hours, removing methane from the atmosphere and sequestering carbon dioxide into its compost output.

“When we put these metrics and data in front of lieutenant governors, state assembly leaders and Congress, they can’t believe the technology exists,” Nguyen said. “We have been going through a very long process — resilience and perseverance — seven years of meeting with lawmakers from as many states as we can, and at the federal level, explaining how this works. We’ve collected a number of leaders who support what we’re trying to do, and now we’re trying to navigate the funding part.”

While Nguyen waits for financing to funnel through government agencies, he envisions building food-waste recycling centers across the U.S. He says the first flagship center will most likely be in Los Angeles. “The California Department of Transportation needs 390,000 tons of compost each year to beautify the landscape and roads,” he said.

In an offtake agreement, California will stamp the compost produced from NuWin FWRD’s industrial-size machine as a certified, high-nutrient fertilizer, enabling Nguyen to sell it to agriculturalists and gardeners. “We’re trying to figure out a process where farmers grow the food, it gets shipped to the stores, people buy it, they create the waste, it goes into our machines, we produce fertilizer and give it back to the farmers. We’re trying to close that loop,” Nguyen said.

Additionally, he hopes to provide waste-pickup and drop-off services to restaurants, hotels, grocery stores, schools and private homes. Nguyen’s machines can sift and grind organic debris ranging from chicken bones to tree limbs, before the enzymes break it down further. “The only thing we don’t want is the plastic and Styrofoam packaging,” he said.

NuWin FWRD’s centralized processing model presents an advantage to transform food disposal at JMU, using the output to maintain its green spaces. “We could easily put one or two machines on campus, because the transport of the food waste from the dining halls isn’t far,” Nguyen said. “Then we make it part of a program that students participate in, so they can learn how waste management is changing for the future.”

“Students may not know it right now, but trust me, what I developed in myself because of JMU brought me here to this moment,” he said. “Wherever I go, whatever I do, I’m aware that I represent JMU.”

With the food-waste industry expected to hit $400 million worldwide regarding business opportunities, Nguyen continues to educate stakeholders and the government on generating new, green jobs and the environmental impact of diverting millions of tons of waste from landfills.

“We are dependent on their participation to make this real and give it the support it needs,” he emphasized. “We want them to take food waste as seriously as they take getting gas-guzzling cars off the road.”