Oil, obfuscation and the open sea: How an IA professor investigated illegal oil laundering

News

SUMMARY: Intelligence Analysis professor Giangiuseppe Pili and his team used open-source data to examine ships illegally transporting sanctioned Russian oil.

It's nighttime. Two rusted, barnacled ships — scions of shell companies — float dangerously close to each other. Their purpose is clear: a covert oil transfer. Beneath them, waves as black as the oil being exchanged reflect the illicit nature of their operation. The origin of the oil? A sanctioned nation waging a war of annexation, evading international laws.

While this scene may seem like a plot straight out of a James Bond movie, it's unfolding in real life. As Giangiuseppe Pili, professor of Intelligence Analysis, uncovers in his report, "Red flags: Russian oil tradecraft in the Mediterranean Sea," scores of ships engage in these shadowy operations to evade oil sanctions.

Pili collaborated with Alessio Armenzoni, an analyst with the Open-Source Center (London), and researcher Gary Kessler on the investigation. Before joining JMU, Pili tracked North Korean ships for the Royal United Services Institute, the oldest think tank in the U.K. Armenzoni, already researching Russian oil laundering, reached out to Pili, who eagerly accepted the invitation to collaborate. Serving as team lead and analyst, Pili led the team through a six-month investigation.

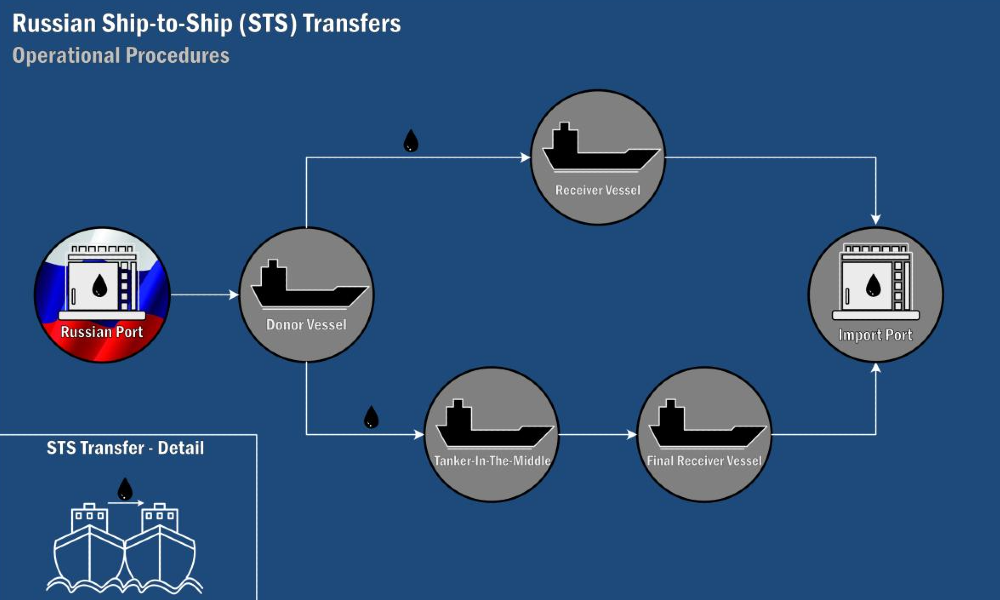

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, sanctions have been placed on the transport and sale of Russian oil, a critical part of Russia's economy. To bypass these sanctions, shell companies and bad actors engage in oil laundering operations. "You want to disguise the origin of your oil," Pili said. "You send the oil to a ship, transfer it to another ship, and maybe there could be three ships. You want to put as many steps between the starting and endpoints."

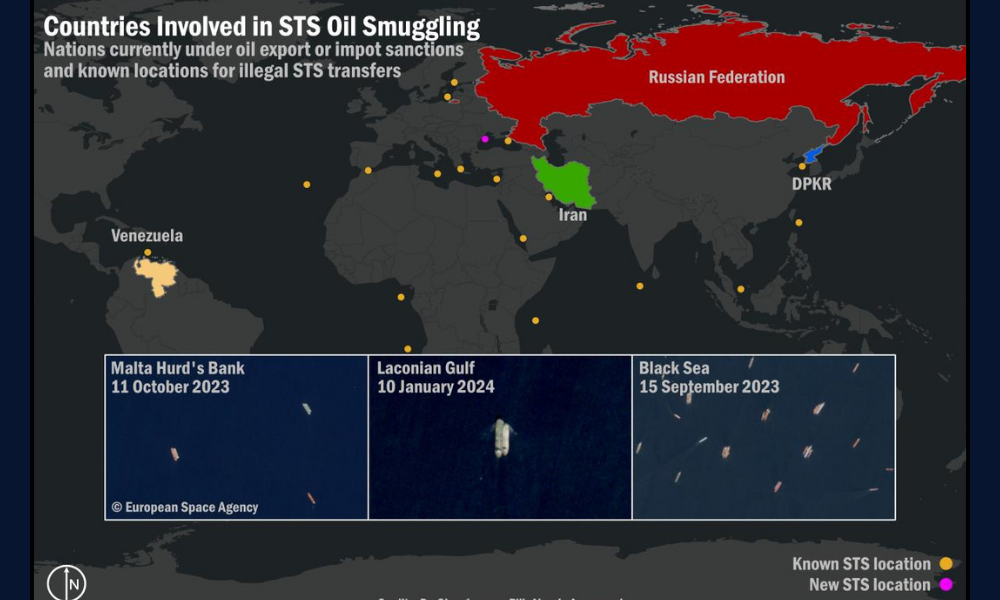

These operations primarily occur in the Mediterranean Sea, whose calmer waters and central location are ideal for such risky maneuvers. Ships can easily sail through the Strait of Gibraltar or the Suez Canal to reach the rest of the world.

However, ships conducting ship-to-ship (STS) oil transfers don't have free reign across the Mediterranean. Due to sanctions, ships carrying Russian oil avoid NATO countries, and non-NATO countries are reluctant to allow what Pili calls "an ecological bomb ready to explode" in their waters.

"The Mediterranean Sea is big," Pili said, "but there are only a handful of locations where an STS transfer can happen. That's why the places are important, and if you bust them, it's a big thing because they need to invent something new or go someplace else."

The report identified four locations for STS transfers: the Laconian Gulf, near Greece; Cueta, a city on the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar; Hurd's Bank, a reef near Malta; and a new site near Constanța, off Romania's coast. Pili's team selected two ships for their case study.

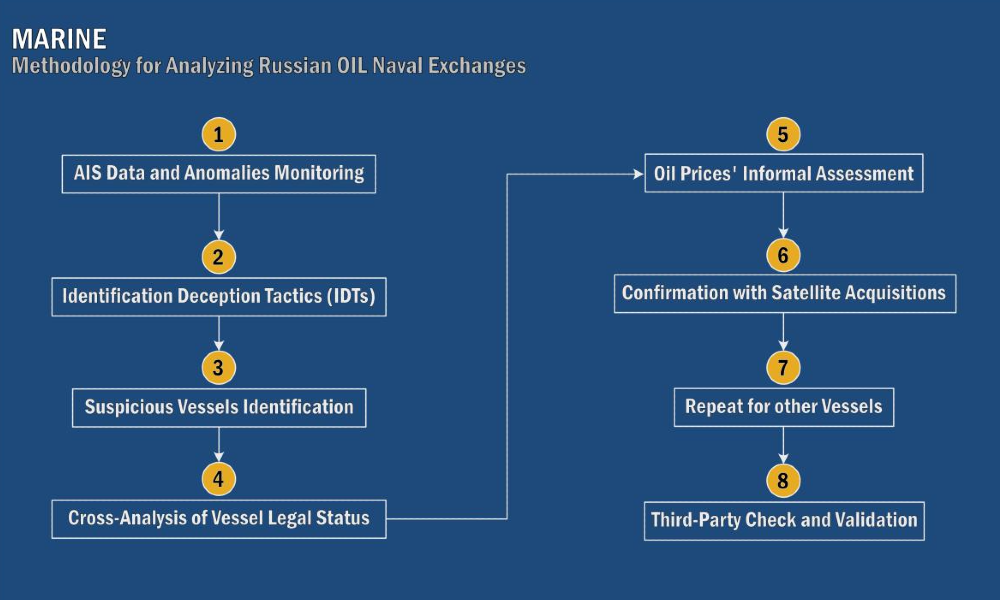

The ships were tracked using open-source tools and data publicly accessible to anyone — in stark contrast to the secrecy often associated with intelligence work. However, like all data, it required an analyst's expertise to piece the puzzle together.

The team relied on satellite imagery from the European Space Agency, business and maritime records, Automatic Identification System logs, and other data. AIS is crucial, as all ships are required to keep it activated. If a ship turns off AIS — an illegal act since it interferes with search and rescue operations — it often indicates a suspicious activity or an attempt to avoid detection. Pili and his team tracked ships already flagged for suspected oil laundering, carefully verifying the data. "We knew that it was true; it was correct. Our due diligence was done," he said.

Instead of focusing on individual ships, Pili took a broader, strategic approach. "If you have 80 ships, you need to prove the movements and actions of each one," he explains. He focused on how widespread and significant this operation was — "where it was happening, why and how we could prove it." This high-level analysis allows Pili's findings to apply to any suspect ship.

To help decision-makers and analysts, Pili and the team developed the Methodology for Analyzing Russian oil Naval Exchanges (MARINE), which was presented to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Conference on Maritime Cyber Security (MarCas). Their algorithm quickly caught the attention of international institutions and investigators, as it is an open-source tool to identify sanction evaders. The MARINE approach offers a systematic way for analysts to determine whether a ship is involved in oil laundering. It can be applied to any vessel without relying on potentially limited algorithms. Beyond Russian cases, the MARINE approach is also applicable to other sanctioned nations, like Venezuela, Iran and North Korea.

At the end of the eight-step process, the MARINE approach results in one of three outcomes: clean, seemingly compliant but suspect, or clearly involved in suspicious activity. If the ship falls into one of the latter two categories, MARINE advises authorities, such as the U.S. Department of State and the International Maritime Organization, to blacklist the vessel. "Once blacklisted, basically anything you do with the ship is illegal," Pili said.

Additionally, countries can assert authority over STS hotspots and force ships to move to rougher waters, increasing the risks. "Every operation has a price; every operation is risky," Pili said. "If you move into areas where you don't want to be, you increase the risk level and the associated costs. The goal is to make oil laundering as risky as possible so that companies behind these ships are forced to cut their losses."

Following the report by the U.S. Naval Institute, Pili and his team received attention from Bloomberg, the Norwegian journal Aftenposten, the University of Munich, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the International Maritime Organization, and a U.K. lobbyist group, among others. "This is the first time we've reached people with incredible financial resources," said Pili, appreciative of the recognition.

|

“With the clear outcomes, the MARINE approach provides, decision-makers should be better informed on how to combat Russian oil laundering.” |

Pili and his team are developing reports on Russia's presence in the Mediterranean and sea drones. Both will be published by the NATO Defense College.

Pili continues to educate and empower Intelligence Analysis students by actively involving them in his research. He currently leads three student groups working on NATO projects and a geospatial intelligence project for RUSI that focuses on North Korea's Chemical Weapons Program.

Images courtesy of Giangiuseppe Pili and Alessio Armenzoni