Green Book house a ‘time capsule’ rich in Black history

Featured Stories

SUMMARY: JMU is helping lead an effort to preserve the long, remarkable history of the city’s last remaining Green Book-listed property.

Hear more episodes and subscribe to the podcast at the Being the Change podcast page.

When faculty from James Madison and Eastern Mennonite universities started researching Harrisonburg’s last remaining Green Book house, they were thrilled at the wealth of history they unearthed.

Dating to the early 1900s, the two-story house at 252 N. Mason St. has witnessed at least three distinct eras — as a successful woman-owned boarding house, a Green Book safe place for Black travelers and the lifelong home of siblings Henry and Lois Rouser.

A remarkable community treasure, the Ida M. Francis House, named for the Rousers’ grandmother, has welcomed the likes of Duke Ellington’s and Count Basie’s bands, and prominent Black inventor and scientist George Washington Carver. At the end of its Green Book era in 1962, the house survived the city’s sweeping Urban Renewal Project that demolished much of the Northeast neighborhood’s Black-owned homes and businesses.

Now, more than 60 years later, JMU and EMU faculty are sifting through rooms of documents, photos and decor that will add depth to the stories that helped define a community. “This is a time capsule. I mean, they threw away nothing,” said Harrisonburg Mayor Deanna Reed, whose father, William, inherited the house from Lois Rouser in 2022.

|

“Here you have a house full of papers and books that is, in a way, its own archive.” — Mollie Godfrey, JMU |

Mayor Reed, who was raised on stories of the homeowners and their famous visitors, understood the important role the house has played in local history. “We realized, ‘Okay, we got something special here,’” she said. “I knew that this was too big for me and my family to handle.” So she and her father reached out to local experts to help them plan a future for the property.

The Green Book house preservation team includes Mollie Godfrey (English; African, African American, and Diaspora Studies Center) and Carole Nash (School of Integrated Sciences; Mountain Valley Archaeology) from JMU; Mark Metzler Sawin (History; Honors Program) from EMU; and JMU Libraries.

Recently, the team secured a $5,000 grant from Virginia Humanities, $1,700 of which funded a summer research assistant to transcribe interviews Sawin conducted over the summer with community members who are knowledgeable about the home’s history. The team also has an oral history of the house, transcribed from cassette tapes the Rousers recorded in a 2002 interview with local writer and historian Ruth Toliver. “Having their actual voices and words is a really wonderful find,” Sawin said.

The team worked with an architectural historian to nominate the house to the Virginia Landmarks Register, and in June their application was approved by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Then, in September, the house and property were placed on the National Register of Historic Places. “It means a lot to the city, and we want to make sure that we take care and respect the legacy of this house,” Mayor Reed said.

At the corner of Urban Renewal

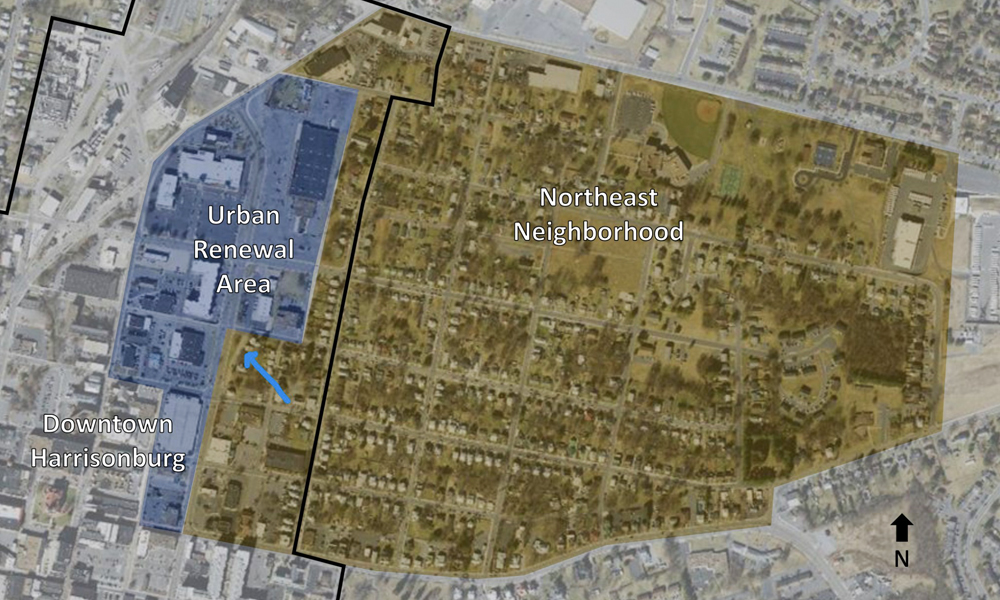

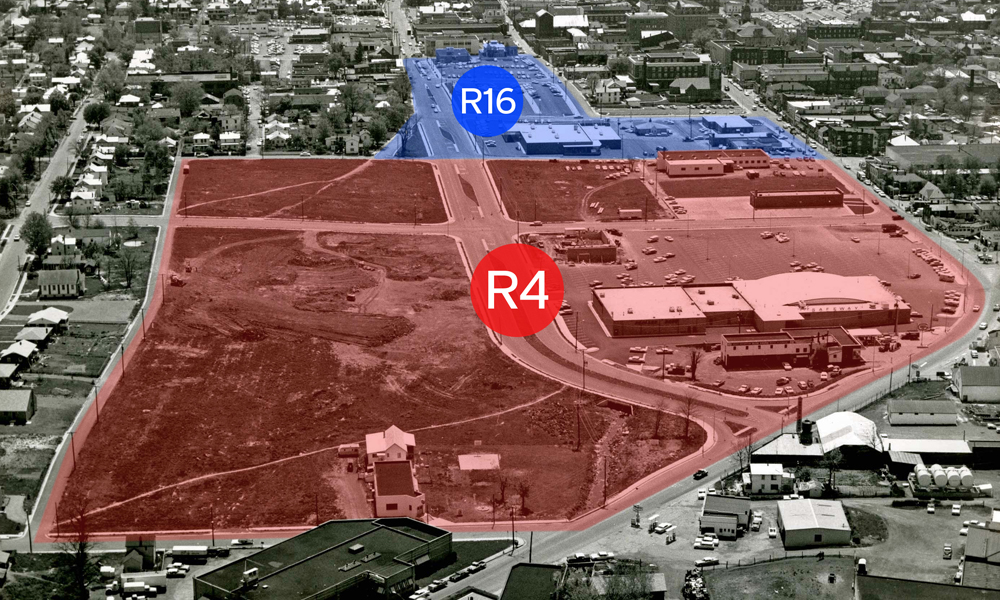

Located in the heart of Harrisonburg’s Northeast neighborhood, the Ida M. Francis House is one of only four historic structures on Mason Street that survived the city’s efforts in the early 1960s to remove “blighted” and “slum” areas to supposedly make way for more modern buildings and low-income housing.

“All the houses across the street in both directions, all the businesses, were taken out,” Sawin said.

Through the use of federal funding from the Housing Act of 1949, also known as the Taft-Ellender-Wagner Act, which sought similar results in cities nationwide, the local Urban Renewal effort displaced 166 families from the downtown area as well as several Black-owned businesses. “People felt as if their community had been taken away from them — decimated,” Nash said.

The neighborhood changed rapidly from 1960 to 1962, Sawin said, followed by racial desegregation in 1965, which closed the Lucy F. Simms School. The school, which served African American students from Harrisonburg and surrounding areas from 1938 to 1965, “was in many ways the heart of the community,” Sawin said.

Urban Renewal targeted Black communities, which saw lasting effects over the following decades, including the loss of local businesses, community centers and family homes. In Harrisonburg, the redevelopment of the Mason Street corridor divided the city’s Northeast neighborhood from the rest of downtown — an issue that Mayor Reed said persists to this day.

A Community Connectors Program grant secured by the city in September 2023 seeks to bridge the two areas. “There’s a lot of history that we own,” Mayor Reed said. “To have something like this [historic house] sitting here is just a blessing for the city.”

She also hopes that bringing more attention to the house and its history will bring recognition to the city’s many successful Black entrepreneurs of the past. “People already knew this house existed,” she said, “but now it’s another opportunity for people who are interested in history to come visit Harrisonburg and learn about our rich Black history.”

The last local Green Book house

The five-bedroom, one-bathroom Mrs. Ida Francis Tourist Home was one of several in Harrisonburg to be included in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide published by New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green that listed hotels and motels, restaurants, tourist homes, and other locations safe for African Americans during segregation, when many places wouldn’t serve Black people after nightfall or at all.

Updated yearly from 1938 to 1967, the Green Book grew to list locations in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., plus Bermuda, Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean.

At its height, Virginia had more than 300 locations in the Green Book. Most of those have since been demolished, with only about a third remaining today. The Francis house was on the list in the 1950s and early 1960s.

The Green Book was “a nationally recognized, historical phenomenon,” said Godfrey, who connected Mayor Reed with Tiffany Cole and Kate Morris from JMU Libraries’ Special Collections to consult on producing an inventory of papers found in the Francis house. Cole and Morris volunteered their time and knowledge as supportive experts on archives. “Having a house here in Harrisonburg allows us to tell the story of Harrisonburg in ways that connect to that [and] celebrate local history,” Godfrey said.

The house being in such great condition greatly increases its historical value, Godfrey shared. “Here you have a house full of papers and books that is, in a way, its own archive,” she said. “It’s a paper record, as well as a physical record, of a history that, like many other places, we don’t have access to anymore.”

Preserving the house is especially important for the Shenandoah Valley, which didn’t have that many Green Book locations to begin with, said Nash, an archaeologist and historic preservationist. “When you have the opportunity to talk with people who are still alive and who knew the people who lived in the house and who know the history of the house, that just enriches everything that we know about it and the way that it’s interpreted,” she said.

“We see this as just the starting point for what can happen with the interpretation of the house and how it might be used by the community and how it is going to further the story of the Green Book houses, but also how it’s going to further the story of Northeast Harrisonburg,” Nash added. “It’s really important work to be done.”

A thriving Black middle class

|

“It gives you great images of this active, hip, well-dressed, having-a-good-time Black community in Harrisonburg that I just don’t think is a story that we’ve told, and honestly is a story that’s largely forgotten.” — Mark Metzler Sawin, EMU |

“I think often the story we tell of African American history, we don’t tell the story of this really thriving middle class that was really doing amazing things, starting businesses,” Sawin said. “This is an amazing property for so many reasons.”

In the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Ida Mae Francis was a single woman running a business after her husband died — and later alongside her daughter, Mary Elizabeth “Pete” Francis.

Being a businessperson didn’t start with her either, Sawin said. Her parents and her late husband’s parents were also local business owners. “This is a generational story of Black-owned businesses, of a thriving and really innovative Black community life,” he said. “It’s super rich in that sense.”

A photo album found in the house shows pictures of the home from the 1920s and 1930s, and the people who lived or stayed there. “It gives you great images of this active, hip, well-dressed, having-a-good-time Black community in Harrisonburg that I just don’t think is a story that we’ve told, and honestly is a story that’s largely forgotten,” Sawin said.

Pete had two children, Henry and Lois, who grew up in the boarding house and later helped run the tourist home.

“We always knew that this house was special because they would talk about the people that would stay there,” Mayor Reed said.

|

“People already knew this house existed, but now it’s another opportunity for people who are interested in history to come visit Harrisonburg and learn about our rich Black history.” — Mayor Deanna Reed |

Members of the Count Basie and Duke Ellington bands were among the guests at the home. “They vividly would tell those stories,” she said of the Rousers.

Entertainers with a Black-owned circus called Silas Green from New Orleans stayed at the house one time, her father recalled.

Additionally, George Washington Carver stayed in 1928 when he was in town for speaking engagements at Madison College and Bridgewater College. He also gifted their grandmother two vases that are still in the house. “They talked about him the most,” Mayor Reed recalled.

Sawin has been putting together the story of the house, while Nash, some of her students and Godfrey fill in the gaps through the larger context of the history of the neighborhood and city.

“When we think about smaller Black communities like Harrisonburg, they often get left out of the story of Black history, because we tend to focus on bigger cities or big national figures,” Godfrey said. “And so, these smaller spaces get left out of the story altogether. Having a house here in Harrisonburg allows us to tell the story of Harrisonburg in ways that connect to that national history.”

The legacy of the Rousers

“We called her Snooky; that was her nickname,” Mayor Reed said. “And her brother, Henry, we called him Bubbles.”

“They kept meticulous books,” she said of the siblings’ finances and local history, which dated to their grandmother’s time running the business. “They clearly took care of the upkeep of the home.”

|

“When we think about smaller Black communities like Harrisonburg, they often get left out of the story of Black history ... Having a house here allows us to tell the story of Harrisonburg in ways that connect to that national history.” — Mollie Godfrey, JMU |

After Urban Renewal decimated the neighborhood, the Francis/Rouser family decided to close their boarding house. The desegregation of Harrisonburg Public Schools, which would make Black-only boarding houses less necessary, was still another three years away. But by the early 1960s, the family didn’t need the extra income or have the space for boarders, Sawin said.

Ida Mae, who was 87 years old and no longer needed to work, lived at the house along with Henry and Lois; their mother, Pete; and Harold Yokley, Pete’s second husband, starting in 1946. The siblings and Yokley all had good jobs, Sawin said. So the family moved on to other things.

Lois went to work in the sewing department at the Joseph Ney’s department store and later Ney’s House of Fashion. She attended First Baptist Church and was a member of the Order of Eastern Star with Mayor Reed’s grandmother, Carmelita Bundy, and aunt Doris Harper Allen, who made outstanding contributions to the community and has a residence hall named for her on the JMU campus.

Henry served with the Army in Germany, working on vehicle parts. Then he used his talents to work in parts at a car dealership before bagging groceries at Mick or Mack.

Harold Yokley ultimately worked 60 years as a waiter at The Arcade and was a well-known figure in the community, Sawin said.

“Ida Mae Francis lived to be 101, passing away in 1976,” he said. “Her daughter, Pete, passed away just eight years later, and Pete’s husband, Harold, died in 1998, leaving just Lois and Henry in the house together, neither ever marrying.”

Although they ran a boarding house for 50 years and worked in public jobs, William Reed recalled that the siblings typically kept to themselves. “They were very private,” he said. “Very intelligent. They were tremendous gardeners.”

After years of living down the street from Henry and Lois, Reed noticed they needed help keeping up at home. “So, I started helping them,” he said. But he never expected that Lois would leave him the house and property. “I never asked them for anything,” he said. “When she gifted it to me, I was really surprised.”

Quickly determining the level of local history they had there, Mayor Reed contacted Godfrey, who encouraged her to reach out to Sawin and Nash to help uncover its past.

“We had to have a team,” said William Reed.

“This is another great partnership that we have with JMU,” his daughter agreed. Having university resources is so important for bringing community projects to fruition, she said. “It has allowed us to preserve this history. We couldn’t have done this without the support of both universities.”

Furthermore, she said it’s helping them realize the dreams that Lois had for the house. “What Lois wanted is that students learn the history.”

Looking to the future

|

“We see this as the starting point for what can happen with the interpretation of the house ... how it is going to further the story of the Green Book houses, but also how it’s going to further the story of Northeast Harrisonburg.” — Carole Nash, JMU |

People often think the National Register of Historic Places lists “places where important people lived or important things happened,” Nash said. But the register is really “designed to tell America’s story through standing structures and archeological sites that are significant. This is one of those places, [and] it’s hiding in plain sight.”

After the team obtained the Rapid Grant from Virginia Humanities, Nash’s nonprofit, Mountain Valley Archaeology, received the grant to dispense the funding. MVA works with the region’s communities to research and promote cultural heritage through education, citizen science and focused research, said Nash, who has an office and lab in Mount Crawford, Virginia.

Funding has been used to hire researcher Mariam Ismail (’24M) to transcribe historical documents and recordings, and architectural historian Dan Pezzoni from Landmark Preservation Associates to write the application for National Register status. Geography majors Aidan McCarthy (’24) and Alex DeChants (’24) mapped yard features like the gardens — information that will be used to restore the property.

“[The house is] eligible today because it is intact,” Nash said. Additionally, the house and furniture look almost exactly the way it did in 1962. “The question now is, ‘Where do we go with what we know? How do we tell this story?’”

Some ideas the team has for the house include an educational resource that is part museum, part bed-and-breakfast, and part community landmark. But they’re still discussing the possibilities. “It requires expertise, and it requires time,” Nash said.

The team wanted to secure the National Register designation in part to open doors to benefits like tax breaks. Additionally, Mayor Reed hopes the house will aid in helping the community heal generational wounds.

She was the first African American woman elected to the city council in 2016 and was appointed mayor of Harrisonburg in 2017. “Now, we are majority African American and majority women,” she said of the council.

Still, there’s much work to do. Urban Renewal “was not that long ago,” she said. There are people living in town who “can still remember the burning of the buildings, the burning of the homes.”

Furthermore, the thriving Black middle class of the early 20th century hasn’t yet returned. “Harrisonburg has intentionally said that we are going to heal those wounds,” she said. And preserving the city’s last Green Book house is a crucial part of that mission.

“There’s a wonderful story to tell,” said Sawin. “There are amazing resources, but it’s unclear still exactly how this will all fit together.”

One thing, he said, is clear: “It’s really important to keep this in the hands of the community.”