The MAC holds several archaeological finding from around the world, many of which were gifts from Drs. John and Bessie Sawhill, former Professors of Classics at JMU. Julianne White (Class of '24), former MAC Student Assistant who is currrently pursing a Graduate Degree in Archaeology at the University of Virginia, wrote this text as an introduction to the collection, focusing on the difference between and importance of the provenance and provenience regarding the MAC's archaeological collection.

A quick look through our eMuseum displays the breadth of the Madison Art Collection’s (MAC) cultural and archaeological holdings. The majority of the objects in our collection were donations from private collectors, and passed through many hands before coming under our care. The history of an object can be quickly lost when it is transferred from between many hands. Private collectors, who typically do not have the resources to develop sophisticated cataloging systems, can quite easily lose this information. The loss of provenience is especially detrimental to archaeological artifacts, and causes many issues for museums.

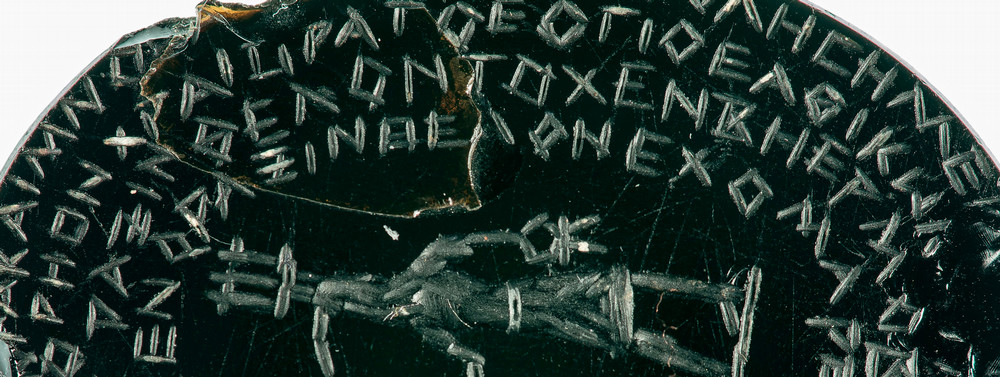

Though they sound quite similar, provenance and provenience provide two different pieces of information. Provenance is the history of an object's ownership, from the moment of its making to the person or institution that currently cares for it. Provenience on the other hand, refers to the precise location of an object’s archaeological discovery. Modern archaeologists are diligent in their efforts to record provenience information while in the field. Today, this documentation usually includes an object's origin on horizontal, vertical, and stratigraphic horizons, drawings of features, and soil quality. Such information helps to discern an object’s purpose and function. For example, if a vessel is found in a fireplace, it is more likely to have been used for cooking rather than food storage.

The loss of provenience is a loss of much valuable information about an object. One of the largest pitfalls of this is the loss of site context. Oftentimes, objects are dated through techniques that rely on the comparison of site features, diagnostic artifacts, and other stratigraphic information. Many kinds of objects have remained stable in form and style for a great span of time, so the aforementioned information is essential to providing an accurate date estimation. For example, we have a few objects in our collection catalogued as Rider figures from the Syrio-Hittite states (76.1.216 and 76.1.217), dated to 1800–1601 BCE. These figures bear a remarkable similarity to European children’s toy figurines in the Medieval era, as late as 2000 years later. If we did not have any prior knowledge, identifying the origin of these objects would be quite difficult.

Or, take lithics for example—stone tools like hand axes (2013.4.3), scrapers (2013.4.6), and projectile points (76.1.1078) rarely have any datable variations; their form remained relatively consistent over the thousands of years they were in use. Furthermore, lithic tools are generally universal. In cases without provenience or provenance, usually the only geographic indicator of a lithics origin is the stone from which it was flintknapped. Temporal attributions can be even more difficult, as dating techniques like radiocarbon dating or thermoluminescence are usually inaccessible to private collectors and museums.

Loss of provenience complicates the process of determining the authenticity of an object. Since looters of archaeological sites and well-meaning hobby archaeologists are disinterested or untrained in archaeological techniques and ethics, their ignorance typically results in the circulation of artifacts with little to no documentation. Without proper documentation to prove where an object was excavated, it is difficult to determine whether it is a real or counterfeit artifact. The authenticity of two Egyptian Scarabs (76.1.1076 and 76.1.1078) at the MAC has been questioned. At one point in time, it was noted that these Ancient Egyptian scarabs are “fakes,” but no additional research, provenance, or provenience was given to support this claim. Without the specialized knowledge of an Egyptologist or the scientific capability to date these objects, the authenticity of these remains difficult to discern.

The loss of provenience is detrimental to archaeological artifacts, and causes many logistical and ethical conundrums. The Madison Art Collection works diligently to research our objects to attribute, and in some cases reconnect them to the cultures that made them. We welcome insights from those outside of our team. If you see an object record that you believe is incorrectly catalogued, please contact us.

Julianne White, Class of 2024